Since the release of the blockbuster film Black Panther (2018), Afrofuturism has become an international buzz word . With its roots in science fiction from the United States, discourse on Afrofuturism has grown to encompass expression from a variety of disciplines and multiple points across the diaspora and the African continent. In Brazil, the rather recent interest in exploring Afrofuturism complements pre-existing efforts to highlight the country’s Black creative producers, including its artists, particularly as most African-descendent artists were historically excluded from mainstream exhibitions and studies. In the twenty-first century, scholars and institutions have expanded their focus from underscoring the role of Black Brazilian artists in national art history, to how these individuals fit into the larger picture of Afro-Atlantic production. This broader contextualization illuminates how Rubem Valentim’s (1922-1991) art and writing relates to Afrofuturism. An examination of the themes of space, futurity, and championing Black equality suggests Afrofuturism’s suitability to a critical reading of Valentim’s plastic works and 1976 manifesto.

Afrofuturism

Although most individuals first heard the word Afrofuturism in 2018, the term was actually coined decades earlier by the U.S. cultural critic Mark Dery in his essay Black to the Future (1993). In this published interview with Black American authors Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose, Dery was attempting to define a genre of speculative fiction that “treats African-American themes and addresses African-American concerns in the context of 20th century technoculture—and, more generally, African-American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically enhanced future.” (DERY, 1993, p. 736). Dery gave a name to a type of production with several common characteristics in which some Black creative producers had already been engaged for decades. Subsequently, individuals began to look as far back as the early twentieth century and identify various individuals and works as proto-Afrofuturist. As such, 1993 is a start date for the term but not Afrofuturist expression itself. In the years since Dery’s essay, scholars have also expanded their scope of inquiry to include disciplines beyond speculative fiction and locations outside the United States. Consideration of a broader range of Afrofuturist production helps to explicate its meaning for Black expression from different times and places.

In Brazil, Afrofuturism is a burgeoning field of inquiry and, thus far, intellectuals and creatives have largely dedicated their examinations to film, speculative fiction, and music. Kênia Freitas is a major leader of the discussion, having curated numerous opportunities in São Paulo for diverse audiences to learn about Afrofuturism and its themes mainly through film (FREITAS, 2015; CENTRO CULTURAL SÃO PAULO, 2021). Other key individuals who are raising awareness about Afrofuturism include Morena Moriah, who has a weekly podcast Afrofuturo, (MORIAH, 2021; BARRETO, 2019) and Fábio Kabral, who is an author of speculative fiction (KABRAL, 2017; LEHNEN, 2021). Brazilians who write and speak about Afrofuturism have primarily focused on national and international contemporary production. However, according to Freitas, Zózimo Bulbul’s film Alma de Olho (1974) is a work of avant-garde Afrofuturist expression that is “directly related to the aesthetics of the movement that came to be formed years after its release,” thereby affirming that earlier Brazilian work can also fall under the umbrella of Afrofuturism (FREITAS in GARRETT, 2015).

Brazilians’ interest in exploring Afrofuturism complements pre-existing efforts to call attention to the role of the country’s African-descendent creative producers, including its artists. Since the late 1980s, there has been a steadily increasing number of exhibitions that feature the work of Black Brazilian artists, largely due to the pioneering efforts of curator and artist Emanoel Araújo. Because most Black Brazilians were excluded from mainstream or “White” art circles and institutions, as their work did not follow the European styles and movements that characterized art production in Brazil since the founding of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, the emphasis was on highlighting the contributions these individuals made to national art history. More recently, intellectuals and institutions have expanded their focus to situating twentieth- and twenty-first century creative producers in the national and international contexts of Black artistic expression. Two relatively recent examples include the wide-ranging show Histórias Afro-atlânticas] (2018), and the solo exhibition Rubem Valentim: Construções Afro-atlânticas] (2018-2019), both of which were organized by the MASP.

The Valentim show exemplified what can be gained by looking at twentieth-century Brazilian artists from a wider perspective. MASP aimed to “reposition [Valentim] in the history of Brazilian and world art …[taking] a broader approach to his work, underlining its political, religious and above all Afro-Brazilian aspects.” (MASP, 2021) In keeping with this goal, several of the essays from the corresponding exhibition catalog demonstrated original approaches to analyzing the artist’s career and work, especially with an Afro-Atlantic emphasis. Equally as important were reproductions of previously unpublished material from several of Valentim’s notebooks dating from the period 1960-1967 (OLIVA, 2018a, p. 24). These sketchbooks, held in a private collection, provide unparalleled insight into the artist’s process and shed light on the range of Valentim’s international influences, particularly as they relate to his exposure to African art while he was based in Europe.

This crossroads of examining Valentim’s work as it relates to international Black artistic expression and using Afrofuturism as a lens through which to view some Black creative production presents an opportune moment to approach one of Brazil’s most important twentieth-century artists from a different angle. Although discussing Valentim within the realm of Afrofuturism may seem anachronistic, the artist expressed interests that have today become frequently cited aspects of Afrofuturism. Consideration of the themes of space, futurity, and championing Black equality in relation to the artist’s plastic works and Manifesto Ainda que Tardio (1976), reveal that Valentim demonstrated certain Afrofuturist characteristics and concerns well before the concept was formalized.

Legenda

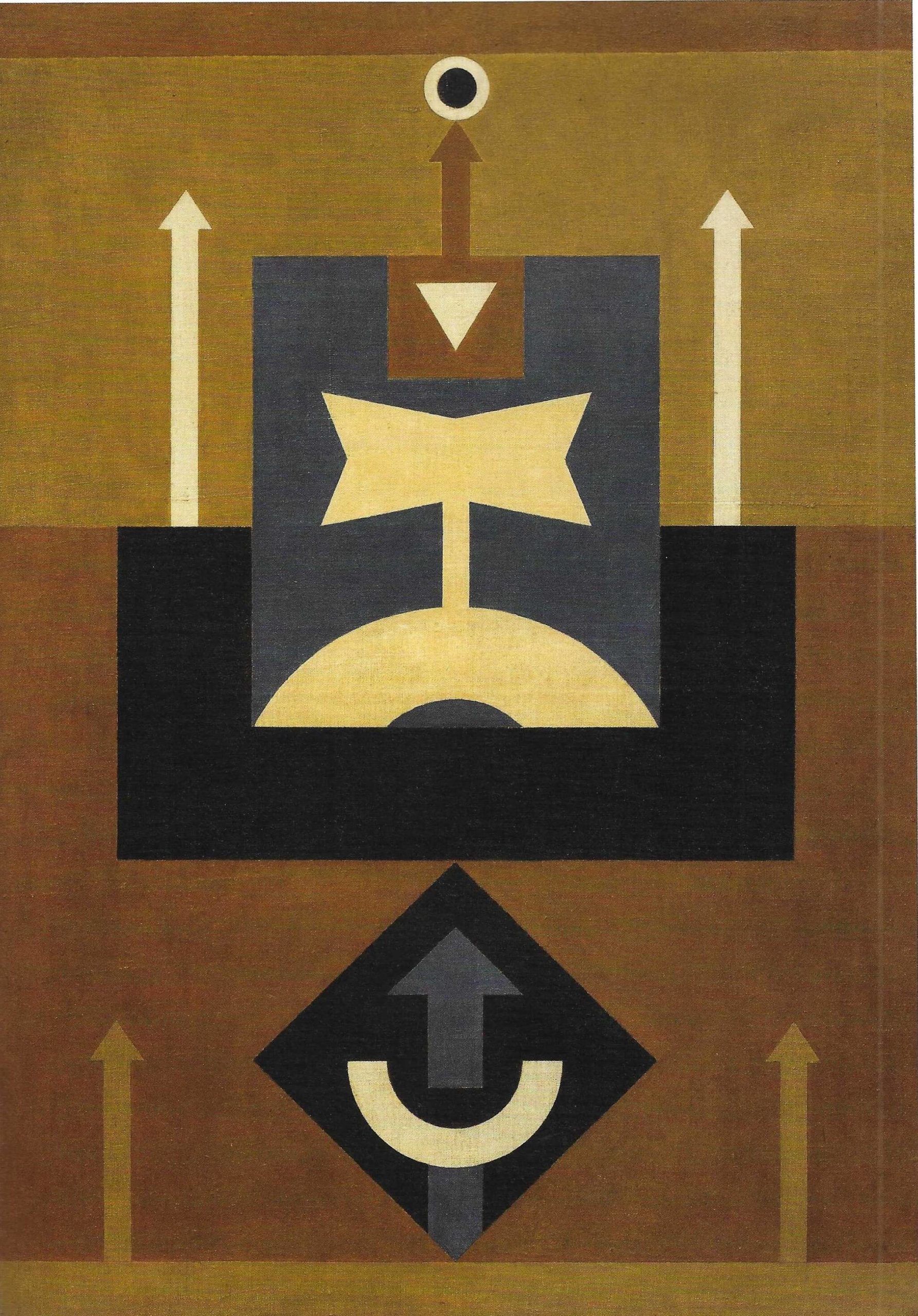

Legenda Rubem Valentim. Composition 17, 1962. Museum of Contemporary Art of Niterói.

Rubem Valentim

Valentim was born in Salvador, Bahia in 1922. He studied dentistry and obtained his degree in 1946. He ultimately abandoned this vocation, however, for his true passion—painting. By the end of the decade, his work was included in regional exhibitions. Valentim created abstract paintings, which he predominantly based on the forms and symbols of the Afro-Brazilian religion Candomblé, having actively studied everything from its religious altars to its liturgical instruments sold at the local markets (VALENTIM, 1967, p. 26). Despite his inclusion in Bahian shows, he was frustrated by the lack of other local artists working in an abstract style and his persistent precarious economic position (VALENTIM, 1967, p. 25; VALENTIM 2001, p. 196). As a result, he left for Rio de Janeiro in 1957.

Soon thereafter, Valentim became known nationally for his signature plastic language with its roots in Brazil’s Northeast. His production remained linked to Bahia foremost through the visual language of Candomblé’s signs and symbols (Fig. 1). As a child, he had attended both Catholic Church services and Candomblé houses with family members VALENTIM 2001, p. 189-193). Following his move to Rio, the artist continued to draw from Candomblé, but also began to incorporate influences from the African-influenced religion of Umbanda.

The 1960s was a significant period in Valentim’s life due to his exposure to a variety of peoples and places. In 1962, he won a foreign travel prize at the XI National Salon of Modern Art (RJ), which enabled him to visit several European countries. He was based in Bristol and London, England in 1963, as his wife was attending the Bath Academy of Art. In Spring of 1964 he relocated to Rome, Italy. During his time abroad he also went to the Netherlands, Germany, Belgium, Austria, Portugal, and France. Valentim traveled to Dakar, Senegal as part of the Brazilian artistic delegation to the 1966 First World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, where he exhibited twelve paintings he had produced while living in Rome. The following year he was invited to teach painting at the University of Brasília’s Central Institute of the Arts and relocated there. Although he left his position after a short time, he remained in the capital.

Unlike most Black Brazilian artists at that time, Valentim’s form of expression, which visually resembled the avant-garde style of Concrete art of the 1950s, earned him acceptance in the country’s mainstream art circles and institutions. Valentim acknowledged similarities between Concrete art and his own abstract, reductionist approach, but asserted that he was never a Concrete artist (VALENTIM in MORAIS, 1994b, p. 78). Nevertheless, in the 1960s and 1970s, curators and art critics praised his non-figural, “internationalism,” which distinguished his production from what they considered the “folkloric” provincial representations of other artists from Bahia VALENTIM, 1970; VALENTIM 1978).. Valentim’s signature style earned him numerous awards during his lifetime. There are permanent galleries of his work at the Museum of Art of Bahia and the Pinacoteca do Estado in São Paulo. As a Black artist, Valentim occupied a rather unique space in the Brazilian art world both during his lifetime and posthumously.

Space

Space exploration is a common theme of Afrofuturist expression. It stems from Dery’s original focus on science fiction and subsequently spread to other mediums as the scope of Afrofuturist discourse grew. Space travel and encounters with foreigners has both fantastical and real-world interpretations. For example, Blacks who were abducted from their homes on the African continent and shipped to foreign lands as part of the Atlantic Slave Trade can be considered early “aliens.” In most Afrofuturist production, outer space presents an alternative to oppressive conditions on earth, thereby safeguarding the survival of Blacks and Black culture. Although undeniably a common subject that has received much attention, even in the United States, not all proto-Afrofuturist artistic production included references to outer space and space travel (WOFFORD, 2017).

Valentim was also concerned with space, but terrestrial space, and even more specifically, Brazilian space. In his Manifesto ainda que tardio, he twice mentions space. He writes, “Nowadays, my art searches for Space: the street, the road, the square—the urbanistic architectural ensembles.” (VALENTIM, 2001, p. 29). Later he states:

My art has an intrinsic monumental sense. It comes from the rite, from the party. It seeks the roots and it could find them in space, as a kind of resocialization of art, belonging to the people. It is the same monumentality as the totems, a point of reference for the entire tribe. My reliefs and objects fundamentally ask for space. I would like to integrate them into urban, architectural, and landscape spaces (VALENTIM, 2001, p. 30).

Valentim thought he could best ensure the continuity of Black Brazilian forms and signs not by leaving earth or even his native country, but by introducing his artworks into everyday public spaces—making an art “belonging to the people.”

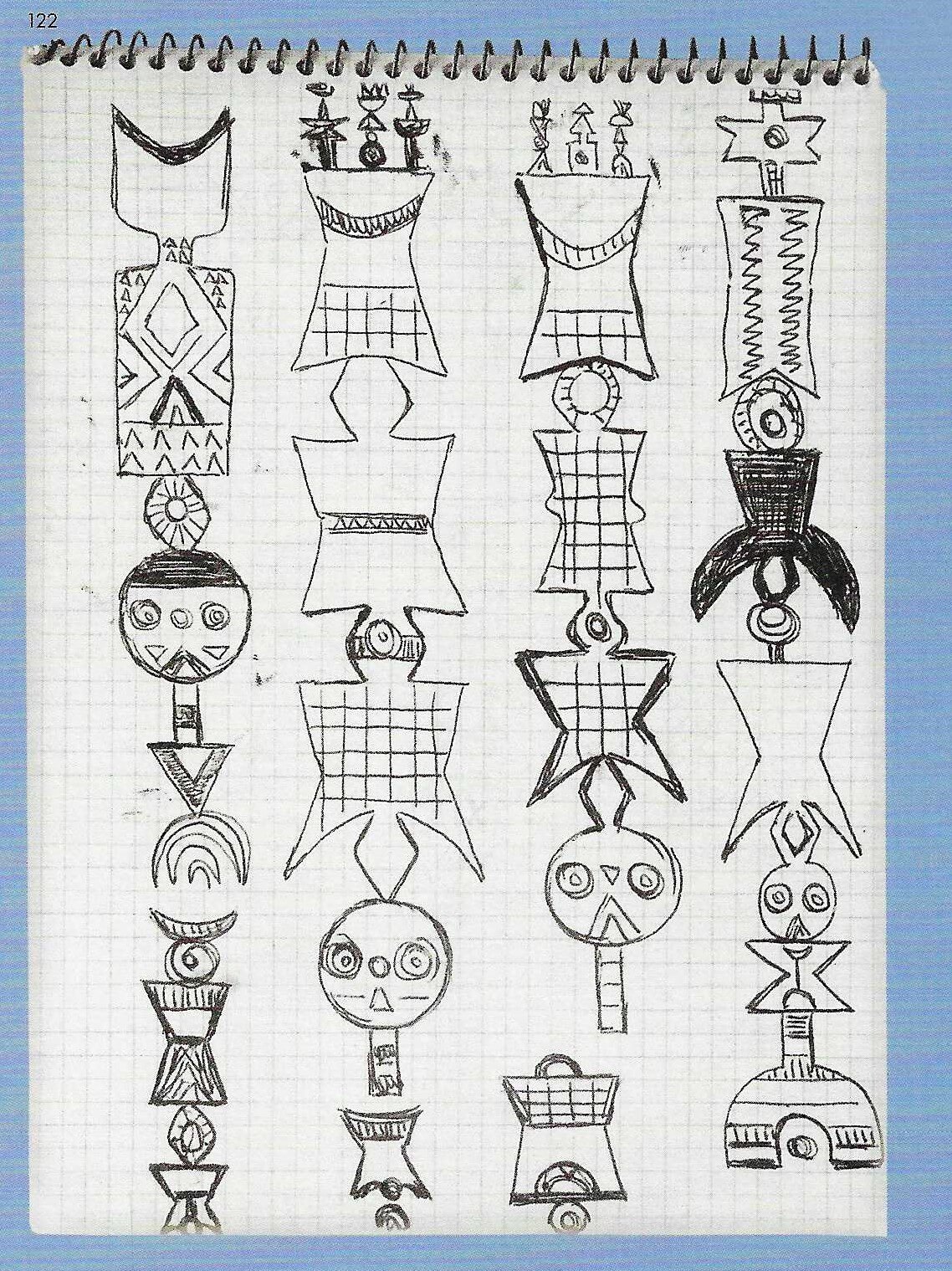

Valentim was likely not referring to his paintings here, but rather his three-dimensional pieces that were inspired by African and Afro-Brazilian forms. When he won the foreign travel prize in 1962, he indicated that he intended to travel to different African countries to experience art and cultures, and study the sources that influenced Brazilian art (TRIBUNA DA IMPRENSA, 1962, p. 2; RODRIGUES, 1963, p. 5). Ultimately, he visited several European countries instead. Nevertheless, he took advantage of studying the African art in different museum collections while abroad. Valentim’s sketches in his notebooks show that he took note of a wide range of African pieces—from Bwa plank masks from Ivory Coast, to Dogon carved doors from Mali, to Kota reliquary figures from Gabon, just to cite a few examples (Fig. 2).

Legenda

Legenda Rubem Valentim. Drawing of the Afro-Baianismo Notebook, n. 122, 1964. Source: PEDROSA, Adriano and OLIVA, Fernando (eds.). Reuben Valentine. Afro-Atlantic Constructions, São Paulo, 2018. [exhibition catalogue].

In 1966, Valentim did go to Africa, but only for a week as part of the Brazilian delegation to the First World Festival of Arts and Culture in Dakar. In newly independent Senegal, President Léopold Sédar Senghor had created the Festival to showcase Black art from around the world that employed aesthetics based on the principles of Negritude (CLEVELAND, 2012). Valentim was one of three artists whose work the Brazilian government sent to this international celebration of “Blackness.” In Dakar, he saw his work shown together with that by Black artists from across Africa and the African diaspora for the first time in his life.

After Valentim returned to Brazil from his time abroad, there were two important developments in his production: first, he recognized the effect that exposure to African art played in his artistic development; and second, he started to create three-dimensional pieces. In 1967, he confirmed that his search to find his plastic language was “enriched [in Europe] through direct contact with the great black art in museums” there (VALENTIM, 1967, p. 26). Additionally, within a year after returning to Brazil, Valentim expanded his form of expression by experimenting first with emblematic reliefs, then emblematic objects, and ultimately three-dimensional pieces (Fig. 3).

Legenda

Legenda Rubem Valentim. Emblematic object 4, 1969, acrylic on wood. Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo.

These free-standing works amalgamate references to African and Afro-Brazilian forms. A comparison of sketches from Valentim’s 1964 notebook Afro-Baianismo, from the artist’s time in Rome, show visual similarities between his renderings of wooden Bwa plank masks and his plans for several three-dimensional pieces (Figs, 2,4). In some of the drawings, the artist has noted that parts for his works should be made from wood or metal, similar to the African sculptures. The plank masks, called nawantantay, from Burkina Faso, have geometric patterns that comprise a system of signs and symbols used in initiations. The combination of the signs communicates a “moral or historical lesson” about ethical behavior, as well as the “myths of the founding of the clans.” (ROY, 2014). In addition to noting the influence that African art had on his development, Valentim also acknowledged the inspiration he took from the “composite, almost geometric organization” of Candomblé’s religious altars or pejis for his three-dimensional works (VALENTIM in MORAES, 1994b, p. 78). Both the African and Afro-Brazilian examples that the artist drew from conveyed meaning through their symbolic languages and geometric nature.

Valentim’s new surroundings in Brasília became an additional source of inspiration after his time abroad and extensive exposure to African art. Brasília was inaugurated as Brazil’s new capital in 1960 and is distinguished by its white, modern architecture and innovative city plan in the shape of an airplane—a “futuristic” representation at that time. Frederico Morais asserts that Valentim’s “semantic leap to 3D could only really take place in Brasília” because of its unique urban space and metaphysical religious character (MORAIS, 1994a, p. 41). In this distinctive atmosphere, the artist “imagined that he could situate his emblematic objects in the green spaces of Brasilia, transforming them into habitable sculptures, city landmarks.”. Rather than solely occupying the interior spaces of museums and galleries, Valentim’s works would inhabit exterior space and become part of the living urban landscape.

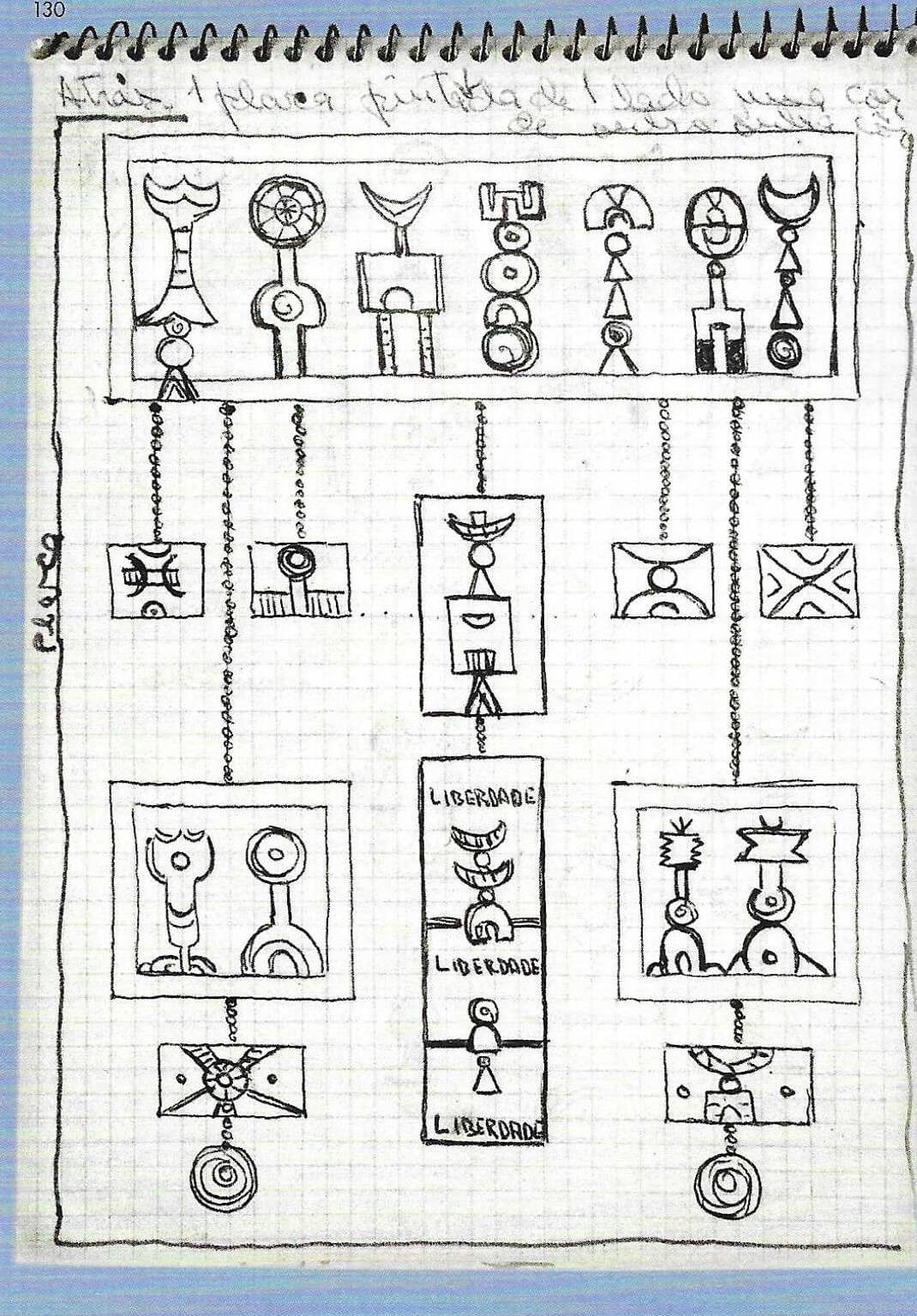

Legenda

Legenda Rubem Valentim. Drawing of the “Afro-Baianismo” Notebook, n. 130, 1964. Source: PEDROSA, Adriano and OLIVA, Fernando (eds.). Reuben Valentine. Afro-Atlantic Constructions, São Paulo, 2018. [exhibition catalogue].

Futurity

As its name suggests, Afrofuturism is concerned with the future. According to Ingrid LaFleur, one way of understanding Afrofuturism is “imagining possible futures through a black cultural lens”( LAFLEUR, 2011). While there has been much emphasis on fantastical aspects of Afrofuturist expression, Afrofuturism can also influence real world outcomes. It is not only concerned with ensuring that Blacks are a part of the future, but also how they want to see the future.

An analysis of one of Valentim’s public sculptures—a successful integration of his work in exterior space—may suggest how the artist wanted to shape the future of Brazil in a visual sense. Marco Sincrético da Cultura Afro-brasileira (1978) is a work in Praça da Sé, near the geographic center of São Paulo (Fig. 5). Roberto Conduru draws a comparison between Valentim’s vertical sculpture and the “pelourinhos, once installed in public squares, where enslaved people suffered physical punishment and were publicly displaced as examples to encourage submission to the system of slavery” (CONDURU, 2018, p. 60-61). São Paulo’s pillory stood in the Largo sete de setembro, just a few minutes away from the current Praça da Sé. According to Conduru, if we understand Marco Sincrético da Cultura Afro-brasileira as a substitute for the past pillories, then Valentim’s sculpture “propos[es] a future that is different from what history had delineated up to then.” (CONDURU 2018, p. 61) Pillories were visual reminders of historical white domination. Marco Sincrético da Cultura Afro-brasileira served as a testament to the power of Black culture. Further, the artist’s “symbolic form of expression was about the future,” as he translated a regional visual language into a plastic language that was more accessible to a wider audience. (CLEVELAND 2017, 219) In its form and placement, Valentim’s art would help to encourage a different path forward for the nation in its treatment of African influences and African-descendent individuals.

Legenda

Legenda Rubem Valentim. Syncretic Brand of Afro-Brazilian Culture, 1978 [1979]. Praça da Sé. Source: https://enciclopedia.itaucultural.org.br/obra4924/marco-sincretico-da-cultura-afro-brasileira.

From a twenty-first century perspective, Valentim’s ideas may not seem to fit a “futuristic” agenda. This apparent dissonance is not unique to Valentim but is part of dominant tendencies regarding futurity in relation to Afrofuturism. For example, in 2019, Moriah pointed out how people tend to conceptualize a distant future—a time characterized by “artificial intelligence and flying cars” when thinking about the future, rather than the next 10 or 30 years (MORIAH, 2019). Afrofuturist author Ale Santos asserts that contemporary Brazil is already in the future because of its dystopian, technological segregation and precarious access to modern-day infrastructure, including electricity” (SANTOS in DUARTE DE SOUZA/STROPASOLAS, 2020). Similarly, Freitas and José Messias identify the Afrofuturist short film Chico (2016) not as a “distant dystopian future, but a speculative film about the dystopia of the [Brazilian] present” (FREITAS/ MESSIAS 2018, p. 403). Envisioning possible futures is more than just fantasy, but frequently involves a reaction to the present.

For Valentim, the future held the possibility of highlighting African influences in Brazil and making their presence a more visible part of public, everyday life. Although his art was well-received in his lifetime, he believed that only in the future would people really grasp the significance of what he produced. According to friend and fellow artist Bené Fonteles, “Once he told me that in the future humanity would know what his work really means, and that each of his works would open the portals of consciousness to another reality, forming itself in the mind and soul of each being” (FONTELES in OLIVA, 2018b, p. 152). Not simply art for art’s sake, Valentim’s pieces would be transformative for future humankind.

Symmetry as Black Liberation and Equality

Brazilian society has long been plagued by power imbalances that leave many Blacks yearning for social equality even in the twenty-first century. The ramifications from colonization on the African continent and slavery across the African diaspora are still felt despite the freedom gained through independence and abolition. More than simply representations of spaceships and escapism, Afrofuturism can be used as a tool for Black liberation and equality. In a 2018 article on why Afrofuturism has such a strong following among young Black Brazilians, Kiratiana Freelon concluded that “Afro-Brazilians are using Afrofuturism to imagine a future more empowered than what even they would call a second-class reality” (FREELON, 2018). In the same article, Kabral asserts that, “For these youth. . . Afrofuturism has become an alternative to the Eurofuturism that is imposed upon us daily” (KABRAL in FREELON, 2018).

Valentim was also concerned with liberation. The word Liberdade appears several times in his notebooks (Fig.4). However, Fernando Oliva points out, Valentim’s “political practice did not manifest itself in an aggressive way, because he was not an artist who would carry flags or join groups or movements” (OLIVA, 2018a, p. 22). Nonetheless, he had a political viewpoint, which he addressed in 1982: “I defend a better distribution of wealth. I am anxious for justice and social balance. It is not by chance that symmetry is the foundation of my constructive language; I seek the same weight from both sides” (VALENTIM in MORAIS, 1982, p. 32). In his manifesto and elsewhere, Valentim touted the cultural and racial mixture of the Brazilian nation. For the artist, “total white is non-being, ditto total black. Only miscegenation creates” (VALENTIM in MORAIS, 1982, p. 32). Both in his art and in his nation, Valentim desired balance.

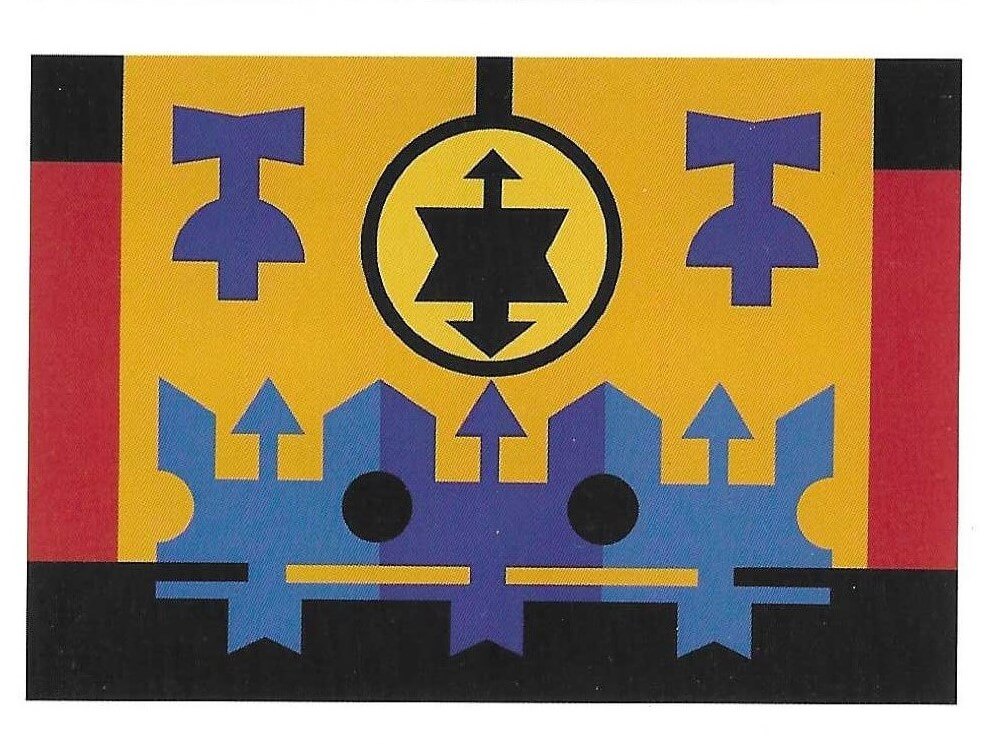

The artist took the oshe Xango as his philosophical and plastic symbol (Fig. 6). Valentim identified it as the “jumping off point for [his] symmetry (VALENTIM in AYALA, 1968) and a “fundamental form of his painting” (VALENTIM, 1967, p. 26). Valentim had frequently incorporated the shape of the oshe—a two-sided axe with a central axis—in his work since early in his career. Conduru suggests that Valentim’s predilection for certain forms had deliberate undertones: “The constant allusion to the symbols, in Umbanda and Candomble, of Eshu and Shango, deities of communication and of justice, respectively, suggest that we see Valentim’s work as a public manifesto for social equality, thus underscoring its political dimension” (CONDURU, 2018, p. 57). For the artist, it was not about one or the other—Black or White—but equality.

Legenda

Legenda Rubem Valentim. Untitled, 1989. Museu Afrobrasil.

Conclusion

In the United States and elsewhere, discourse on Afrofuturism continues to develop, as does the interest in identifying additional examples of Afrofuturist expression. Looking at work from various places and times sheds light on similarities and differences, as creative producers are working from different contexts. Nuanced explorations underscore how individuals engage with common themes in unique ways.

Valentim’s perspective and desires as reflected in his manifesto, published interviews, and other statements may not seem as “forward-thinking” as some contemporary expressions of Afrofuturism. Further, his plastic production does not demonstrate all of the most often-discussed aspects of Afrofuturist work. Nevertheless, efforts in Brazil to locate Black artists’ production in a broader Afro-Atlantic context are revealing additional connections and prompting new questions, including about Afrofuturism. Further, Black Brazilian scholars and creatives are leading the discussion on Afrofuturism and embracing it as a tool for analyzing and understanding Black expression. Where perhaps other terms and labels originating from outside the country have contributed to the marginalization of Black Brazilian artists, Afrofuturism is an empowering means to not only understand individual expression, but also shared ideas, concerns, and influences from across the diaspora and the African continent.

References

AYALA, Walmir. . Rubem Valentim: A Arte Está Viva. Jornal do Brasil, January 27, 1968.

BARRETO, Victor Hugo. 2019. Afrofuturism: Looking at the World from an Afrocentric Point of View. Torus Time Lab, June 3, 2019. Available: https://medium.com/torustimelab/afrofuturism-looking-at-the-world-from-an-afrocentric-point-of-view-1dbb1faacd61. Accessed on February 28, 2022.

CENTRO CULTURAL SÃO PAULO. Mostra Afrofuturismo – Centro Cultural São Paulo. Accessed September 1, 2021. Available: http://centrocultural.sp.gov.br/2021/08/27/mostra-afrofuturismo/. Accessed on February 28, 2022

CLEVELAND, Kimberly. Afro-Brazilian Art as a Prism: A Socio-Political History of Brazil’s Artistic, Diplomaticand Economic Confluences in the Twentieth Century. Luso-Brazilian Review, vol. 49, no. 2 , Dec. 2012. p.102-119. Available:https://doi:10.1353/lbr.2012.0045. Accessed on February 28, 2022.

CLEVELAND, Kimberly. Candomblé as Artistic Inspiration: Syncretic Approaches. In POLK, Patrick et all. (ed.). Axé Bahia: The Power of Art in an Afro-Brazilian Metropolis. Los Angeles: Fowler Museum at UCLA, 2017, p. 204-219.

CONDURU, Roberto. Albeit Late, But on the Eve – Rubem Valentim and Time. In: PEDROSA, Adriana/OLIVA, Fernando (eds.). Rubem Valentim: Afro-Atlantic Constructions. São Paulo: MASP, 2018, p. 53-61

DERY, Marc. Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose. South Atlantic Quarterly. Vol. 92, no. 4 (Fall), 1993, p. 735-778.

DUARTE DE SOUZA, Marina/STROPASOLAS, Pedro. O Afrofuturismo de Ale Santos: ‘Quero Reconstruir o Imaginário Social Brasileiro’. Brasil de Fato, November 24, 2020. Available: https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2020/11/24/o-afrofuturismo-de-ale-santos-quero-reconstruir-o-imaginario-social-brasileiro. Accessed on February 28, 2022.

FREELON, Kiratiana. Why Brazilians are Embracing Afrofuturism. Okay Africa, May 13, 2018. Available: https://www.okayafrica.com/why-brazilians-are-embracing-afrofuturism/Accessed on February 28, 2022.

FREITAS, Kênia. Afrofuturismo: Cinema e Música em uma Diáspora Intergaláctica. São Paulo: Caixa Cultural, 2015.

FREITAS, Kênia/MESSIAS, José.O Futuro será Negro ou não Será: Afrofuturismo versus Afropessimismo – as Distopias do Presente. Imagofagia, vol. 17 April, 2018, p.420-424.

GARRETT, Adriano. Mostra em SP Traz Filmes com Narrativas Alternativas sobre as Populações Negras. Cine Festivais, November 16, 2015. Available: https://cinefestivais.com.br/entrevista-com-kenia-freitas-sobre-a-mostra-afrofuturismo/. Accessed on February 28, 2022.

KABRAL, Fábio. [Afrofuturismo] Nosso Futuro em Nossas Mãos. Medium, May 16, 2017. Available: https://medium.com/revista-subjetiva/afrofuturismo-nosso-futuro-em-nossas-m%C3%A3os-e4354af2af0c. Accessed on February 28, 2022.

LAFLEUR, Ingrid. Visual Aesthetics of Afrofuturism. TEDx Fort Green Salon, YouTube, September 25, 2011. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x7bCaSzk9Zc. Accessed on February 28, 2022.

LEHNEN, Leila. Decolonizing Fictions: The Afrofuturist Aesthetics of Fábio Kabral. Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas, vol. 54, no. 1, July, 2021, p.: 80-89. Available: https://doi.org/10.1080/08905762.2021.1909258. Accessed on February 28, 2022.

MASP. Rubem Valentim: Afro-Atlantic Constructions. 2021. Available: https://masp.org.br/en/exhibitions/rubem-valentim-afro-atlantic-constructions. Accessed September 1, 2021

MORAIS, Frederico. Toda Criação é Mestiça. O Globo, January 21, 1982.

MORAIS, Frederico. Brasília. In Rubem Valentim: Construção e Símbolo, Rio de Janeiro: Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, 1994a, p. 41-43.

MORAIS, Frederico. Biographical Profile. In Rubem Valentim: Construção e Símbolo, Rio de Janeiro: Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, 1994b. p. 77-79.

MORIAH, Morena. Afrofuturo. TEDx Laçador CESMar Porto Alegre, YouTube, May 18, 2019. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=99y4DG-nQu0. Accessed on February 28, 2022.

MORIAH, Morena. Afrofuturo, podcast, spotify, 2022. Available: https://open.spotify.com/show/3r4oXdzrqRt6DPmg3OKw4T. Accessed on February 28, 2022

OLIVA, Fernando. Art, Politics, and Construction in Rubem Valentim. In: PEDROSA, Adriano/OLIVA, Fernando. Rubem Valentim: Afro-Atlantic Constructions. São Paulo: MASP, 2018a, p. 18-25.

OLIVA, Fernando. He Did Not Separate Ethics from Art’: A Conversation with Bené Fonteles about Rubem Valentim. In: PEDROSA, Adriano/OLIVA, Fernando. Rubem Valentim: Afro-Atlantic Constructions. São Paulo: MASP, 2018b, p. 150-153.

RODRIGUES, Augusto. Artes Plásticas. Última Hora, July 8, 1963.

ROY, Christopher. The Art of Burkina Faso. 2014. Available: https://africa.uima.uiowa.edu/topic-essays/show/37?start=52. Accessed September 1, 2021.TRIBUNA DA IMPRENSA. 1962. Arte Moderna. June 5, 1962.

VALENTIM, Rubem. Depoimento. GAM, vol. 5,April, 1967, p. 24-26.

VALENTIM, Rubem. 31 Objetos Emblemáticos e Relevos Emblemas de Rubem Valentim. Rio de Janeiro: MAM, 1970.

VALENTIM, Rubem. Mito e Magia na Arte de Rubem Valentim: Emblemática: 20 Pinturas, 10 Relevos, 10 Esculturas. Rio de Janeiro: Galería Bonino, 1978.

VALENTIM, Rubem. Manifesto Ainda que Tardio. In: FONTELES, Bené/BARIA, Wagner (eds.). Rubem Valentim: Artista da Luz. São Paulo: Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, 2001, p. 27-31.

WOFFORD, Tobias. Afrofutures: Africa and the Aesthetics of Black Revolution. Third Text, vol. 31, no. 5-6,September-November 2017, p. 633-649.