Addressing the silences of traditional historiography is insufficient; I deem it necessary to go further: to question the documentation concerning the gaps, to wonder about the forgotten elements, the gaps, the blank spaces of history. We must conduct an inventory of the archives of silence and make history based on the documents and on the absence of documents (LE GOFF, 1990, p. 107, our translation).

Legenda

Legenda Lasar Segall (Vilnius, Lithuania, 1889 – São Paulo, Brazil, 1957). Ship of Emigrants, 1939. Lasar Segall Museum.

Legenda

Legenda Lasar Segall (Vilnius, Lithuania, 1889 – São Paulo, Brazil, 1957). Profile of Zulmira, 1929. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP)

The museum, its collection and projection of power

Instituted by the recently inducted Board of MAC USP and carried out in partnership with the North-American Getty Foundation, a timely initiative provided circumstances so that in 2021, among other things, three curators with different backgrounds—histories—, who work in different regions of the country—namely: Prof. Dr. Diane Lima, from the Northeast; Prof. Dr. Igor Simões, from the South; and this researcher, who writes from the Southeast—approached the museum’s collection. In this condition, they were given the opportunity to investigate, in the considerable collection of the traditional institution of São Paulo, those artistic productions made by Afro-descendants, derived from or belonging to the Afro-diaspora culture. A relevant and constitutive fact of the project is that, in common, the guest curators share African ancestry as an ethnic condition and proletarian status as a class distinction.

The suggestion about the racial, gender and class composition of the group was—as we will see—in accordance with the purposes of the project, and at least one conclusion stems from this fact: consistent with its history, the current Board, significantly composed of women, proves sensitive to the appeals of its time, notably those that, at present, try to ensure the effectiveness of policies that deepen our still incipient democracy in a conjuncture hitherto characterized by historical and structural inequality of race, gender and class.

Thus, through the work of these curators, MAC USP revisits its own history considering a sensibility that is intended to be critical and decolonizing, hence less averse to a conception of history that wants to be hegemonic, but which—as it is heteronormative and white—is also politically conservative, or frankly reactionary, being, therefore, excluding; and, consequently, racist, misogynist, transphobic, and homophobic.

However, it is possible that, in opposition to conservative values, certain ethical and aesthetic arrangements based on a divergent morality, of solidarity and otherness, subversively appear in the cracks of history. An ideal that in a revolutionary way signals support for an oppressed group, as seems to be the case of a certain fraction of the work of Lithuanian Jew naturalized Brazilian Lasar Segall (1889-1957), German artist Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945) and, perhaps, Brazilian painter Alberto da Veiga Guignard (1896-1962), focusing only on three artists belonging to the collection of MAC USP.

The flourishing interest of art and cultural institutions in Afro-Brazilian artistic and intellectual production is consistent with (or just reflects) the demands of the market, which, characteristically eager for novelties, sees in the production of minorities a window of opportunity to increase its own expansion. The concepts concerning the market preclude simplifications since it is, to an extent, a microcosm, a fraction that reflects quite complex structures that govern and organize society itself.

Regarding the current interest in the symbolic production of excluded populations, it should be noted, however, that there is a correlation between this interest and the resurgence of the historic struggle of those oppressed for their basic civil rights.

As workers, artists and cultural producers face situations that affect the way they produce and the type of work they perform; they are subject to objective historical conditions, according to which their work is carried out, not only as a result of these conditions, but also as criticism of and reaction to them.

In the long process of enslavement to which they were subjected, black women and men had their symbolic production neglected or repressed. The disregard remains until political conditions end up creating visibility for the work of these authors.

Thus, it is reasonable to recognize that the social position of the minoritized majorities is also reflected in the way they are or are not represented in museums—not only in the collections, but mainly in the positions of prestige in their administrations. And that, for example, a feminism essential to women is the result of their struggles against those who oppress them, and it is feminism that creates means for the empowerment of those women who hold the qualifications that makes them suitable for the positions that today they gradually occupy; and in these places they have created conditions that provide voice to other excluded persons.

The Black Lives Matter movement of 2020, triggered by the cruel murder of Afro-American George Floyd by a State security agent, in Washington, has multiple historical precedents both there, in the USA, where he was born, and here, in Brazil, where it still echoes. Apropos, similar movements can be observed among other oppressed social groups, such as native peoples, riverside peoples and other divergent bodies (a universe that, by the way, is quite large, encompassing almost everything that is not white, masculine, slim, and bourgeois).

If we mention the gradual resurgence of these emancipatory social processes, it is because when they escape the epistemic cancellation to which they are usually subjected, they strengthen the repertoire of major events that reinforce and implement a history that comes to have those oppressed, now emancipated, as protagonists. There were many artistic or academic productions that, under the pretext of celebrating fads dear to minorities, were relevant to the point of becoming, themselves, central landmarks in the history of the group they precisely seek to rescue.

In 1988, environmentalist and rubber tapper Francisco Alves Mendes Filho, aka Chico Mendes, was murdered with a shot at the door of his house, in Xapuri, in Acre, undeniable proof that the fight that put an end to the civic-military authoritarian cycle that prevailed among us was far (and still is) from the best outcome. Nevertheless, in October of the same year, the redemocratization process culminated in the proclamation by the National Constituent Assembly of a new Brazilian Constitution, known as the Citizen Constitution.

It was in this context of major social mobilization that, during the celebrations for the Centenary of Abolition, also in 1988, MAM saw the opening of the encyclopedic and still to date benchmark exhibition A Mão Afro-brasileira: Significado da Contribuição Artística e Histórica [The Afro-Brazilian Hand: Meaning of the artistic and historical contribution]. Organized by black and Bahian plastic artist and curator Emanoel Araújo, the exhibition bequeathed to posterity a valuable catalogue, which compiled, in an unprecedented way, hitherto dispersed knowledge on various aspects of the culture of Brazilian Afro-descendants.

This 1988 exhibition is all the more important because it laid the foundations for what would become the pioneering Museu Afro Brasil, established and directed in 2004, in the city of São Paulo, by the same Emanoel Araújo.

In this conjuncture, as part of the celebrations for the centenary of Abolition and still under the coordination of Emanoel Araújo, the significant exhibition Pintores Negros do Oitocentos [Black Painters of the 19th century] was held in the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo art gallery, curated by Prof. José Roberto Teixeira Leite.

Among other merits, this exhibition revealed, or reinforced, the ideas around the competence of the “Afro hand” that extended into domains that prejudice did not allow it to reach. There, the excellence of the artistic production of black academics was amply proven and here, in São Paulo and in the south of the country, where the production of Northeastern artists is even less known, the figure of the Bahian Manuel Raymundo Querino emerged gigantic from the exhibition.

Black, born free in 1851, in Santo Amaro da Purificação, Bahia, he was a polymath, an architect without a degree, an award-winning painter whose works were lost; he was a professor of Geometric Drawing at the Liceu de Artes e Ofícios school in Salvador and at the Órfãos de São Joaquim School in São Joaquim; He was also a prominent abolitionist, republican and militant of the workers’ cause, and was one of the founders of the Worker’s Party of Bahia in 1890. He established newspapers and was, among us, a forerunner of anthropology, as well as an art historian in Bahia. He accomplished all of this in a context deeply characterized by racism and the fierce militancy of the defenders of eugenics, pseudoscience that advocated the superiority of whites over the other races. The fierce Brazilian eugenicists—who, among other things, proposed the extinction of blacks by whitening of the population—were entrenched in the academies, notably in the schools of Law and Medicine and in the newsrooms of newspapers and magazines. This movement, indeed tentacular, yielded at least one work of art that is central to our history, A Redenção de Cã, painted by Spanish Modesto Brocos, in 1895, which can be seen at the National Museum of Fine Arts that safeguards it, in Rio de Janeiro.

Manuel Raymundo Querino died in 1923, a year after the Rio de Janeiro writer Afonso Henriques de Lima Barreto (1881-1922) and the São Paulo Modern Art Week, held in February 1922. Querino’s theses are contained in works such as Artistas Baianos – Biographical Indications, of 1909, As Artes na Bahia – Escorço de uma Contribuição Histórica, also of 1909, A Raça Africana e seus Costumes na Bahia, of 1916, and O Colono Preto como Fator de Civilização Brasileira, of 1918.

If the pioneering spirit represented by Manuel Raymundo Querino’s intellectual production is little known, especially by the southeastern academic intelligence, this is mainly due to the way higher education institutions were constituted in Brazil, and how they, based on this constitution, reflect the political and economic power of the social group that promotes them. The racism and misogyny that denies black women, black men, indigenous persons and women a leading role in history is a consequence of this history. It is no coincidence that several higher education institutions only reluctantly implement racial quota policies. This has evident repercussions on the production of the narratives of history, which will consider those excluded as subordinate, mere objects of a picturesque or exotic interest, unless they are, metaphorically, promoted, serving the interests of those who seek to forge symbols of a national identity, aiming to maintain the power of the elites. As in the second Empire, which symbolically promoted indigenous peoples, or as in the period of the Estado Novo dictatorship led by Getúlio Vargas, which co-opted popular artists, usually samba artists, to promote the regime’s ideals. That is one of the history keys that established policies based on which the collections of some of our museums are constituted: these collections compose mosaics of images that mirror, on the walls of the “white cubes,” a whiteness that reflects only the very white reason that gives it meaning.

Manuel Querino, Lima Barreto, and brothers and painters João and Arthur Timoteo were the protagonists of a type of modern sensibility that did not appear in the canon promoted in São Paulo through the 1922 Modern Art Week, and their racial and social origins cannot be disregarded when we consider this absence. They were contemporaries of Rio de Janeiro-born journalist, critic and writer Luiz Gonzaga Duque Estrada (1863-1911), known in the literary world as Gonzaga Duque. Born in a wealthy family, descended from Swedes on his mother’s side, he was the author of A Arte Brasileira , which constituted an important attempt to examine the Brazilian art’s development processes from the colonial period until the time it was published in 1888. In addition to this study, Gonzaga Duque published, in 1910 Graves e Frívolos [Serious and Frivolous], a new venture into the universe of the history of art critique. Gonzaga Duque also published, in 1900, the remarkable symbolist novel Mocidade Morta. Focusing on the daily life of a group of bohemian characters inspired by artists, critics, bourgeois and aristocrats of the period in which the artist lived, a mixture of chronicle of customs and social criticism, the novel presents a vivid yet sophisticated narrative that fictionalizes the period’s art scene.

Tadeu Chiarelli, who taught at the Department of Arts at USP, was head curator of MAM SP (1996–2000), director of MAC USP (2010–2014) and of Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo (2015-2017), and was one of those responsible for introducing Gonzaga Duque in academic studies. As shown in his introductory text to the 1995 reprint of the work Gonzaga Duque, Gonzaga-Duque: A Moldura e o Quadro da Arte Brasileira [Gonzaga Duque: The Frame and the Painting of the Brazilian Art], the art critic remains indispensable to studies focusing on the art of the period. However, that does not imply acclaiming him as the only authorized voice to testify about this history.

It is notable that in the pages of his A Arte Brasileira [The Brazilian Art], Gonzaga Duque mentions, in tones that are almost always complimentary, the works of Afro-descendant artists, notably those of Estevão Roberto da Silva (1844-1891), perhaps the most important black painter of the period and undoubtedly one of the best painters of the “still life” genre among all the others.

It is interesting that, as a professor at the Department of Arts at USP, Chiarelli was a “promoter” of the oeuvre of Gonzaga Duque, having presented it to his students—among them, me, the writer of this text. For some of us, that was the first mention of black artists who worked in the sphere of the Rio de Janeiro Fine Arts Academy in the 19th century.

As director of the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo art gallery, Chiarelli’s administration was important for the recognition of the Afro-Brazilian and Afro-descendant artistic production, and led to a policy aimed at acquiring works of these artists. In that, he was preceded by artist and curator Emanoel Araújo.

This prospection of Afro-Diasporic references in the collection of MAC USP resulted in the interrelations between politics, diversity and art, the administration of the dissemination and circulation of the latter, and the indissociable role of education in this process.

The actions promoted by education (an intersectional subject par excellence)—or, rather, the debates around the issues imposed by art education through museums—remain indispensable in a context where very little is done to promote public policies that make accessible the knowledge built from what is provided by the collections of our museums.

Legenda

Legenda Maureen Bisilliat. Untitled, 1968. Series: Black Skin. Maureen Bisilliat/Instituto Moreira Salles.

Legenda

Legenda Lasar Segall (Vilnius, Lithuania, 1889 – São Paulo, Brazil, 1957). Red Hill, 1926. Lasar Segall Museum.

Education

It is understood that art is a social product that can contest or confirm through its symbolic projection, which achieves the predominance of a group, class or gender over others. Therefore, it is no mere coincidence that it is often safeguarded in buildings whose architectural parti corroborate the taste of the class that designed them. If that is true, the thesis according to which the exercise of curatorship is a politically committed activity is also true, since the arrangement of the works, associated with other factors (such as the aforementioned architecture of the space that houses them), confirm an option that is featured to the detriment of others. This choice—political—translates into pedagogy, into a fulfillment that incorporates methods and practices that make supposedly useful content accessible for the assimilation of a specific public.

The exercise of curatorship is critical, which is also understood as an exercise in pedagogy, as an exercise in education that explores the content of the works for the construction of knowledge.

The current experiment carried out by the MAC USP board, in partnership with the Getty Foundation, is committed to education, which is part of its ontology, and leads us to consider a neologism that defines the experiment as “Educuratorship,” a sort of crossing between critical curatorial thought and decolonizing pedagogical practice, which results in the possibility of providing, prospectively, new meanings to contents contained in works, artifacts and documents.

The necessary decolonization of curricula involves their blackening, the recognition of figures such as Manuel Querino, without, however, disregarding that which in the work of—for example—Gonzaga Duque can serve to reinforce the necessary debate on racial and gender diversity in the history of Brazil in general and of art in particular. Recognizing that such history is deficient is, at the same time, recognizing that there is, indeed, any notion of artistic “well-doing” that meets the taste of a certain class, a certain group, a certain gender. And that, despite that, even in the midst of cultural institutions tutored during periods of political exception and democratic scarcity, some alternative views of formation, circulation (extroversion) and management of collections flourished subversively, contradicting the adverse milieu. Even in the times when, among us, the censorship imposed by the civic-military dictatorship was active, contexts were created that challenged this control.

Accordingly, the education divisions of museum institutions had, and continue to have, a preponderant role. In some cases, these divisions are constituted almost as “autonomous zones” for the exercise of creative freedom, interaction with the public and production of knowledge.

If the works in the collections safeguarded in our museums, and in MAC USP in particular, do not reflect the plurality of gender, race and class present in our society—on the contrary, they reaffirm the prevalence of some over others in a society divided by classes —, the same cannot be said of some pedagogical policies and practices implemented throughout the history of these institutions and of the very university that MAC USP is, after all, an important subsidiary institution.

Today, the works contained in these institutions build narratives that can and are subverted by the experience of the same social agents that, in these works, are peripheral to the central context. The artistic production of these agents requires spaces to circulate, in parallel with the advance of the social/political struggle by the portion of society interested in their own emancipation. From the dialectical relationship promoted in the friction between the hegemonic and counter-hegemonic narratives, an overcoming, or synthesis, may result, which renders obsolete propositions that are averse to the plurality of gender, race and class. New vocabularies are gradually established, new semantics that, obviously, challenge current concepts about the teaching of art and history, the types of museums and their counterparts.

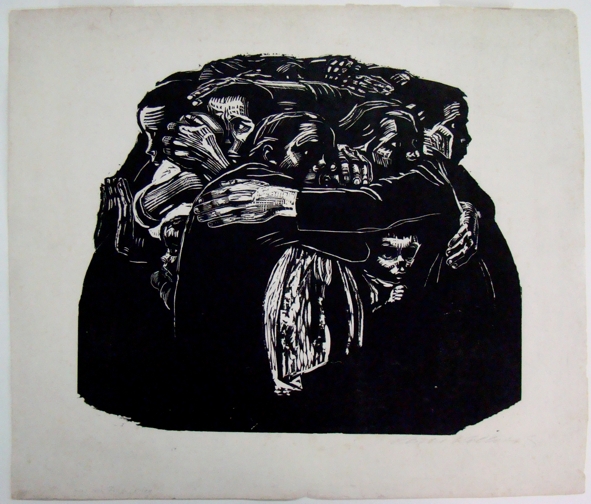

Legenda

Legenda Käthe Kollwitz. Die Mütter [The Mothers], 1922-1923. Series: Sieben Holzschnitte zum Krieg. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

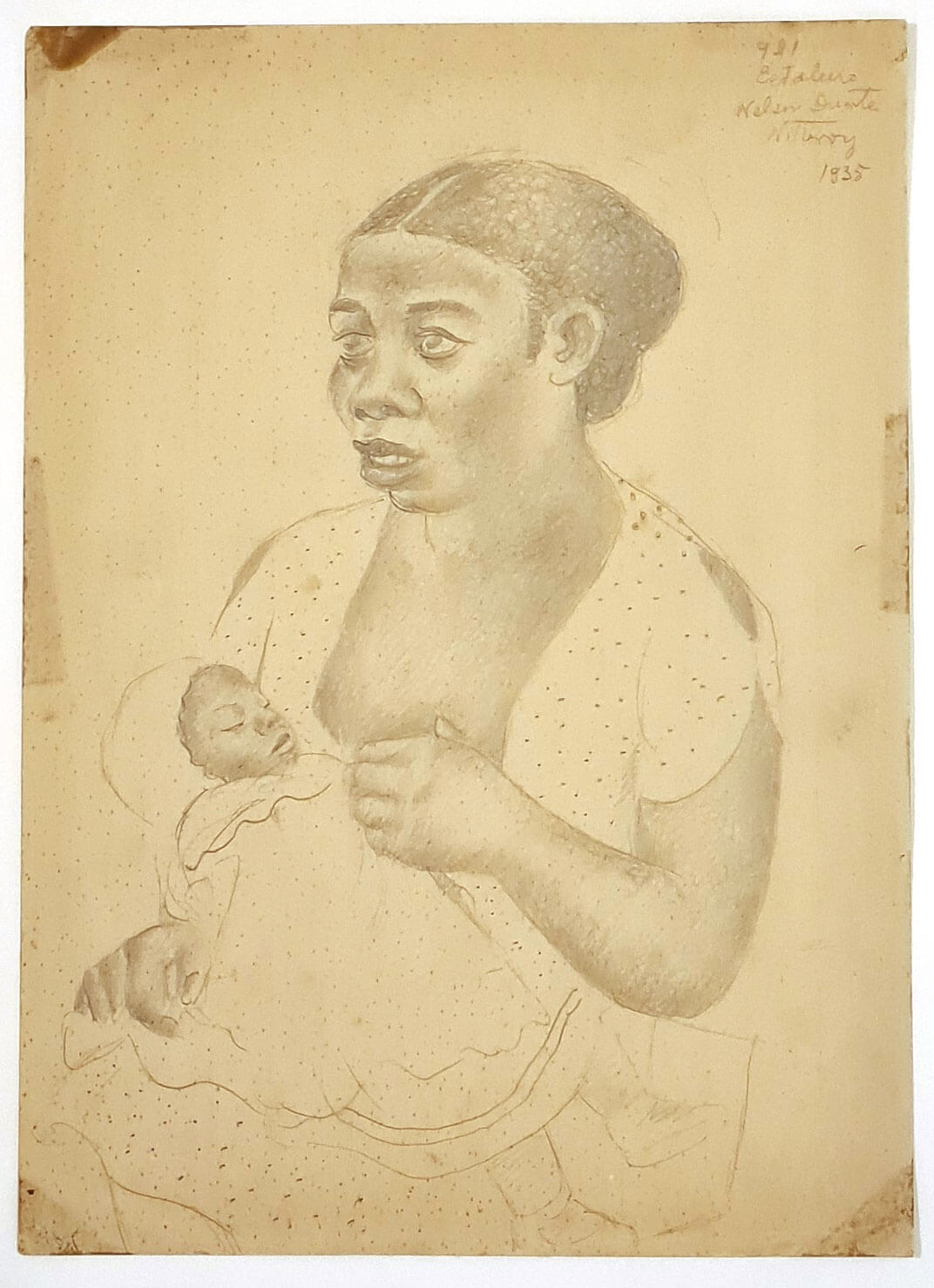

Legenda

Legenda Emiliano Di Cavalcanti. Untitled [woman and child], 1935. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

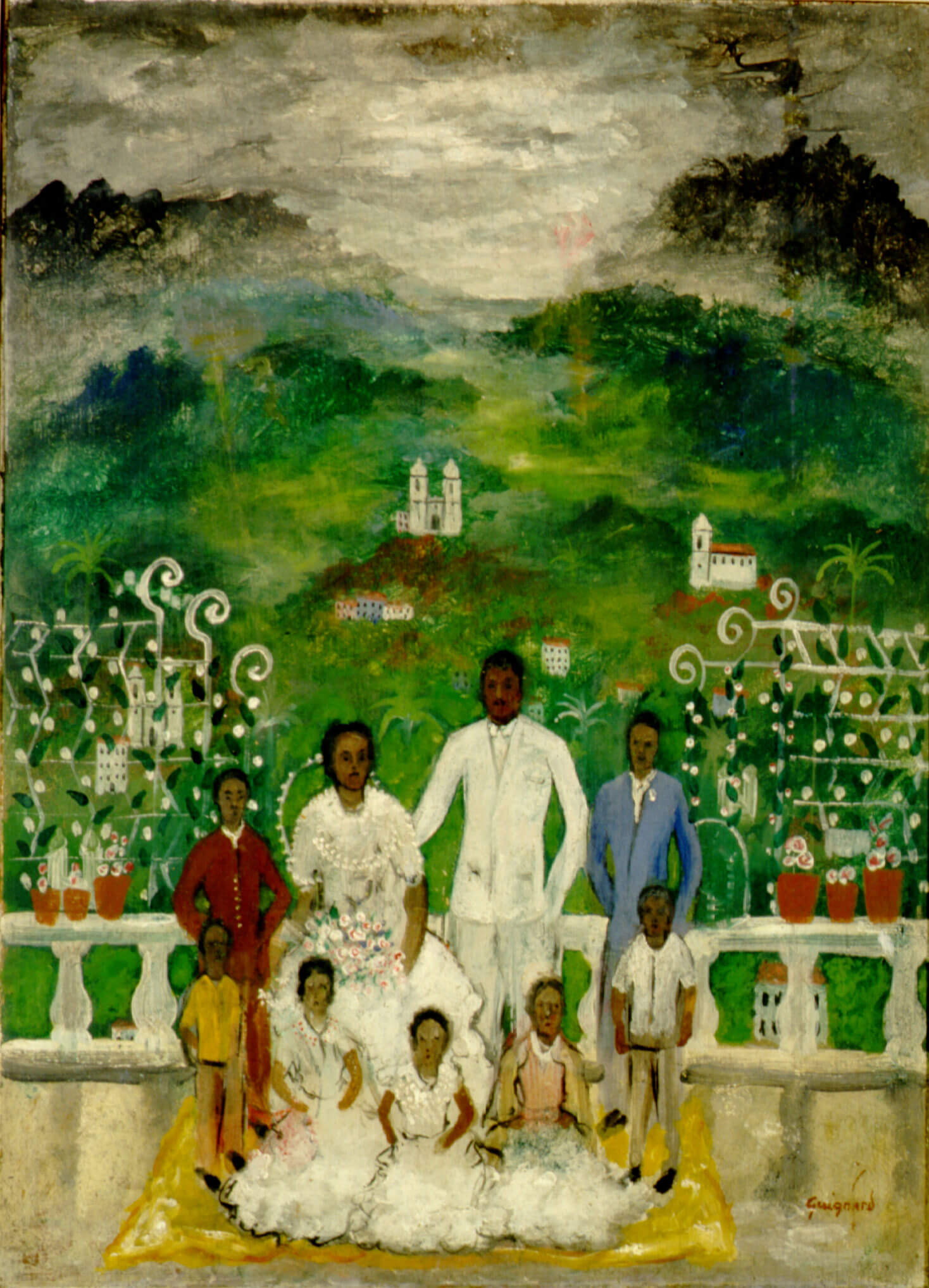

Legenda

Legenda Alberto da Veiga Guignard. Family Feast, no date. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

Perfil de Zulmira and the black skin

The abundant literature on the work of Lithuanian painter, engraver and sculptor Lasar Segall points to the importance that his work acquired during his lifetime and posthumously. In this literary production, several aspects of his life and work are addressed, at times emphasizing the social dimension that it often presents. Born in the city of Vilna, Lithuania, in 1891, Lasar Segall was deeply marked by his condition of Jew. An important part of his work develops this circumstance, denouncing the persecutions to which his people were subjected, and which had, as the worst consequence, the genocide promoted against them by the Nazis during World War II.

A relevant portion of his fruitful production presents—in paintings, drawings, and engravings—black men and women that the artist met in Brazil. As we have seen, black men and women were the theme in works made by non-blacks who generally presented them as mere subjects of interest to the artist, who sought in the landscape an exotic, picturesque element; their humanity, in these cases, is submerged, and their subalternity is highlighted. Segall, conversely, represents them based on experiences that made him permeable to the suffering of others, notably of those social groups that, like his own, were victims persecuted and harmed by prejudice and racism. This adherence is such that the artist will even make self-portraits in which he presents himself as a black man.

Those who, like us, participate in the terrible experience to which racism subjects black women, black men and indigenous people in Brazil, are certainly impacted by the painting Navio de emigrantes [Emigrants’ ship], executed between 1939 and 1941. There is much of “slave ship” in this monumental painting, despite the “human cargo” represented in it is not human beings kidnapped in Africa and converted into enslaved people in the Americas. The painting translates, in its sepia tones, the melancholy, fatigue and hope of the humble people who—involuntarily, and facing all kinds of uncertainty—are forced to leave their homeland in pursuit of better days in a less hostile setting. Beyond the technical qualities and the precision in the execution of his work, these characteristics, of a conceptual nature, already draw attention to that which Mário de Andrade called “interested art,” committed to humanitarian causes.

It is no coincidence that Segall’s work was persecuted and considered “degenerate” by the supporters of the Nazi order established in Germany after the rise of Adolf Hitler and his group. An indelible mark of the regime was, precisely, the systematic persecution of artists and intellectuals not aligned with the new fascist order, which in 1937 resulted, for example, in the exhibition “Degenerate Art,” held in Munich, with major repercussion. The exhibition was intended to present the work of the modernists as a result of warped and unhealthy sensibilities, and gathered around 650 works by artists representing the avant-garde of modern art in Europe, such as Marc Chagall, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Otto Dix, Piet Mondrian, Käthe Kollwitz and Lasar Segall.

In 2018, MAC USP and the Lasar Segall Museum organized the important exhibition A “Arte Degenerada” de Lasar Segall – A perseguição à arte moderna em tempos de guerra [The “Degenerate Art” by Lasar Segall – The persecution of modern art in times of war], curated by Helouise Costa, from MAC USP, and Daniel Rincon Caires, from the Lasar Segall Museum. The exhibition was followed by an international seminar that considered the repercussion of the Degenerate Art exhibition in Brazil and in the anti-fascist struggle that it also sparked.

Who knows if the resilience and humanitarianism of this artist, an émigré Jew, does not coincide with the humanity of those people he portrayed? People that a daily life of ordeals could not belittle.

Thus, the painting entitled Perfil de Zulmira [Zulmira’s profile], created in 1928, which belongs to the MAC USP collection, attracts new interest; interest, in fact, already pioneered by the educational division of that museum, through mediation proposals prepared by its division coordinator, Maria Angela Francoio. Which confirms the—let’s say—avant-gardism of museum education, and this one in particular.

This ability to reveal the dignity of the person through poetic artifice is recurrent in the artist. The very size of the painting participates in this strategy, since its small size (62.5 x 54 cm) and the careful treatment in the execution of the work invite us to closely observe the portrait of the black girl who, dressed in pink, poses against a background of bright, light colors, on which there is a white cloth decorated with pale roses that, like an aura, highlights the girl’s silhouette without angles. A girl who, being an individual and having an identity, we know her name is Zulmira and not simply “the black one.”

The black skin that prompted Segall required him to develop a palette, that is, a series of colors that, when mixed, would result in the desired shade. This palette, due to his European education, was perhaps unknown to him, but the results he obtained when painting black characters only reinforce the idea that he dedicated himself to the subject with the same zeal as he dedicated to other works he produced. This black skin seems to have absorbed the interest of another foreign artist who, among us, produced important work, English photographer Maureen Bisilliat in her series Pele Preta [Black Skin], of which MAC USP has at least one piece. The photographer gives vent to an affection of a political vocation: the series of photos was shot in 1968, annus mirabillis of the struggles for civil rights around the world. Bisilliat’s commitment was such that her work ended up becoming one of the most significant in the photography, history and memory division of the Afro Brasil Museum in São Paulo, where, by the way, this researcher had contact with the work.

The series of “Black Madonnas” that Lasar Segall painted, having the painting Morro Vermelho [Red Hill], of 1926 as one of its possible culminating points, is also central to his oeuvre. The painting, of an “archaic-mythical” grandeur, repeats in the presentation of the characters a composition that, faithful to the theme, obeys the classical tradition. The figure of the mother who holds the child in her arms observes us with serene gravity; mother and daughter form a triangle centered on the canvas; against this “pyramid” of violet, red, gold and earthy colors is a favela, flanked by imposing palm trees that look more like columns that support the sky; it is the Red Hill, and it is interesting to observe how these shapes of the Red Hill refer to the prow of the Navio de emigrantes [Emigrants’ ship] ; it is the same great triangle of ocher tones. A significant fact of the painting is that the feet of the portrayed mother are shod with a kind of golden slipper. Now, in the representations of black men and women, they are almost always barefoot, because this was characteristic of slaves, and they were forbidden to wear shoes. One of the first measures to be taken when they reached freedom was, precisely, to look for shoes. In the representations of blacks by Brazilian modernists, they are almost always barefoot.

Apropos, would not this militant motherhood be one of the recurring themes in the powerful work of German expressionist artist Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945), also present in the MAC USP collection? In Kollwitz’s work, the mother fights “death” for the lives of her children. Death that—in the mythology engendered by the German artist—is a metaphor for wars and for those who promote them.

MAC USP safeguards an important collection of works on paper by Emiliano Di Cavalcanti (1897–1976). Among them, a powerful drawing made with graphite and quite weakened by the action of time, untitled, made in 1935, drew the attention of this researcher. It is a work that, despite its small size, is grandiose, suggesting monumentality. Here, we have again a black madonna presented in a composition that obeys a triangular shape; the child sleeps on the mother’s lap and—an important detail—is well dressed and wearing shoes. The mother, in turn, has a worried face; her mouth half open and her tired eyes show apprehension. Cavalcanti, as we know, was, at a certain point in his career, a politically engaged artist. The date of this work coincides with the rise of Nazi-fascism in Europe, a time of great tension that preceded the outbreak of World War II.

If Segall and Cavalcanti chose to represent black madonnas in their paintings, Alberto da Veiga Guignard (1896–1962) chose the “sacred family.” In the painting Festa em família [Family party], he presents the portrait of a black family that, in its own way, is prosperous. The artist approaches an aesthetic with a naïf flavor, which makes us consider that the production, said to be popular or naive, deserves to be better assessed. A certain notion involving the so-called “popular art” has the power to preclude its entry into the universe of what we understand as contemporary art. There are few artists with this style in the collection of museums dedicated to contemporary art; nevertheless, Guignard’s refined work has suggested other possibilities of reading and approaching the universe of the art we call popular.

With the exception of Cavalcanti, none of the artists prospected in this immersion is black. His works, however, refer to black men and women, and all, when building their narratives, adopt figurative language. Ceará-born artist Antônio Bandeira, whose birth centenary is celebrated this year, 2022, is black and, conversely, in developing his artistic project, adopts a non-figurative language, which is confirmed in his imposing Flora noturna [Nocturnal flora], an oil on canvas painting completed in 1959. Bandeira died very early, in 1967, in a Paris disturbed by existentialists, anarchists, communists and above all students who, a year later, in 1968, would promote a revolt that almost overthrew the Fifth Republic. Bandeira contradicts the narrative that expects black artists to produce exasperating works of exoticism and sensuality: like Bahians Rommulo Vieira da Conceição and Rubem Valentim, his work is cerebral, without implying nihilistic conceptualism. It only confirms that the sensibility of male and female black artists moves with ease through any territory of art.

I conclude that the experience provided by the prospection for indices of the Afro-Diasporic civilization in the MAC USP collection has a symbolism that goes beyond the event itself, and that such experience is significant for the mentalities committed to the repair of historical injustices. We believe that the experiences of Diane Lima and Igor Simões will greatly expand the scope of this research, and that the pioneering spirit of the initiative marks an extraordinary point in the unusual history of this fundamental institution.

Legenda

Legenda Antonio Bandeira. Flora at night, 1959. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

Reference

LE GOFF, Jacques. História e Memória. São Paulo: Ed. Unicamp, 1990.