Brazilian art was made by white hands. We are facing a project of power that is based on the consolidation of narratives weaved from successive supposedly revolutionary forms, forged by unequivocally disruptive agents, which are central to the construction of a given Brazilianness (SIMIONI, 2013). These stories are certainly nourished by the organization interested in this conglomeration of common ideas, images and political practices called reality. In this path, protagonists who share a dominant identity adherence become evident. The understandings that these subjects have about their work; of the relationship they establish with artistic traditions, the observation of society, and their ability to mobilize them in the works is marked by this condition. The white gaze hierarchizes, segregates and establishes truths, thus placing coloniality as the norm of white-Brazilian art (AMANCIO, 2021).

I understand that we must politicize this process, unveil the connections between “artistic criteria,” politics and otherness and, at the same time, question what was suppressed and theorized and what interdicted generations and more generations of black artists through the most diverse ways. If art is “the experimental exercise of freedom,” having the discourse silenced, ultimately, contributed to our dehumanization in the collective imagination. It is the banalization of violence as a language. Thus, decomposing this project is more than meets the eye. Its guiding threads challenge, at different levels, our lives and, therefore, affect our possibilities of (re)existing on a daily basis. (Fig. 1).

Legenda

Legenda Tarsila do Amaral. A Negra [The Black Woman], 1923. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP)

To demonstrate this point, we will focus on the process of canonization of a work. I am referring to A Negra [The Black Woman], 1923, by Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973), an oil on canvas painting measuring 100 x 81.3 cm. The painting has been part of the MAC USP collection since 1963, when it was donated by the São Paulo Museum of Modern Art (MASP). Therefore, it has been part of the museum’s collection since its foundation, and there’s been over 74 exhibitions in 59 years.

Despite being one of the most celebrated paintings in Brazilian art, having been the subject of studies of dozens of monographic works and, above all, having quite insightful contemporary readings, it seems to me that there are still some aspects in it that have not been sufficiently looked into and that deserve further reflection (FERREIRA, 2017; MEIRA, 2018; OLIVEIRA, 2014; VIDAL, 2011). What place should this work occupy in the debates on the formation of Brazil’s national identity 99 years after its creation?

Let’s examine the painting. Before considering the character, it is better to describe the pictorial exercise that frames the scene. Behind the figure, at head height, we can see some horizontal bands. From left to right, they start along the frame boundaries and follow after the black woman’s body/obstacle. From top to bottom, the first band—dark brown—is half the size of the next band—white. The third band, which is dark blue, has, in turn, three times the dimensions of the first and a particularity: it is interpellated by two tiny bands inside it, painted in a much lighter shade of blue. The one that is more to the right, located at the character’s eye level, has the visible vertex rounded, while the second is a little larger in length and height, perfectly rectangular and arranged diametrically opposed to the first. Then, we have four more bands—this time with uniform thickness—that are increasingly squeezed by the black body that widens from the shoulder. On the right there are also bands, although without a correspondence in terms of colors and dimensions. It is unknown whether there is x, but, if so, how are the figures joined from one side to the other, since the black woman blocks them? They end at the edge of two transversal bands—painted in two shades of green—that protrude from the upper right corner of the canvas and extend to the character’s left shoulder. Still at the height of what is supposed to be her waist, we see some more horizontal bands, this time with irregular sizes, starting from the black body and extending to the edge on the right side of the canvas. The novelty is in a thin red band. However, the same does not occur with the character. It stands out from the background as there is volume in the composition. She is naked. The small face is emphasized by the absence of hair. Also noteworthy are the eyes, which are also small and, set at 45 degrees, look at something that we cannot reach. The Negroid nose, the exaggeratedly large and red lips, and the dark skin leave no doubt that this is a black woman. The robust body is connected to the head by an oval neck and the torso projects forward, judging by the way the character is seated. A deformed breast is projected in front of the right arm; the arm extends across the entire length of her torso, and the hand rests on the left elbow.

The critique and historiography that deal with A Negra have, over the years, made some comparisons. The work has been associated with Manet’s Olympia, Gauguin’s Les seins aux fleurs rouges, Picasso’s Les demoiselles d’Avignon, Léger’s Le petit déjeuner, Lhote’s La negresse, and Brancusi’s The white negress. (MEIRA 2018; VIDAL, 2011). The relation with Cubism, by the way, was pointed out by the critics of Tarsila’s time (CARDOSO, 2016). From a formal point of view, the work and such avant-garde certainly have a certain connection. At that time, the French capital was experiencing negrophilia (CHENG, 2010; DOMINGUES, 2010; SWEENY, 2001). Josephine Baker, Sidney Bechet, Langston Hughes and other Harlem Renaissance artists moved to the City of Light to escape racial segregation in the United States of America (LEININGER-MILLER, 2001). In modernist and European art, figures such as Picasso developed the concept of primitivism further. Tarsila travelled to Paris in 1920 to study at the Académie Julian; she returned to Brazil in 1922, but maintained a relationship with Léger. It is in this context that A Negra was produced by her. Mário de Andrade, in 1923, makes a curious observation addressed to her by correspondence:

But it’s true that I consider you all rednecks in Paris. You have Parisianized yourselves in the epidermis. Tarsila, Tarsila, go back inside yourself. Abandon Gris and Lhote, entrepreneurs of decrepit criticism and decadent aesthesia! Abandon Paris! Tarsila! Tarsila! Tarsila come to the virgin woods, where there is no black art, where there are also no gentle brooks. There are VIRGIN WOODS. I created the virgin-woodism. I’m a virginwoodist. This is what the world, art, Brazil and my dearest Tarsila need. (AMARAL, 2003, p. 140, our translation)

The grandiloquent entreaty of the São Paulo city artist stems from the assessment that Tarsila would be more relevant in the Brazilian context, in forging a renewed nationality. Mário also understands that the path followed by European modernists goes in another direction, which he disapproves of, and even without seeing their works, he realizes that the learning relationship with the avant-gardes will not be decisive for the project he aims to accomplish. However, I understand that A Negra is a work in which Tarsila effectively establishes a relationship also based on her previous experience. The statement that she was inspired—for the creation of Abaporu—by the history of the black women who worked for her family, in addition to the famous photograph of a maid in her travel album, provides consistency to this hypothesis (CHRISTO, 2009; CARDOSO, 2016; RIBEIRO, 1972).

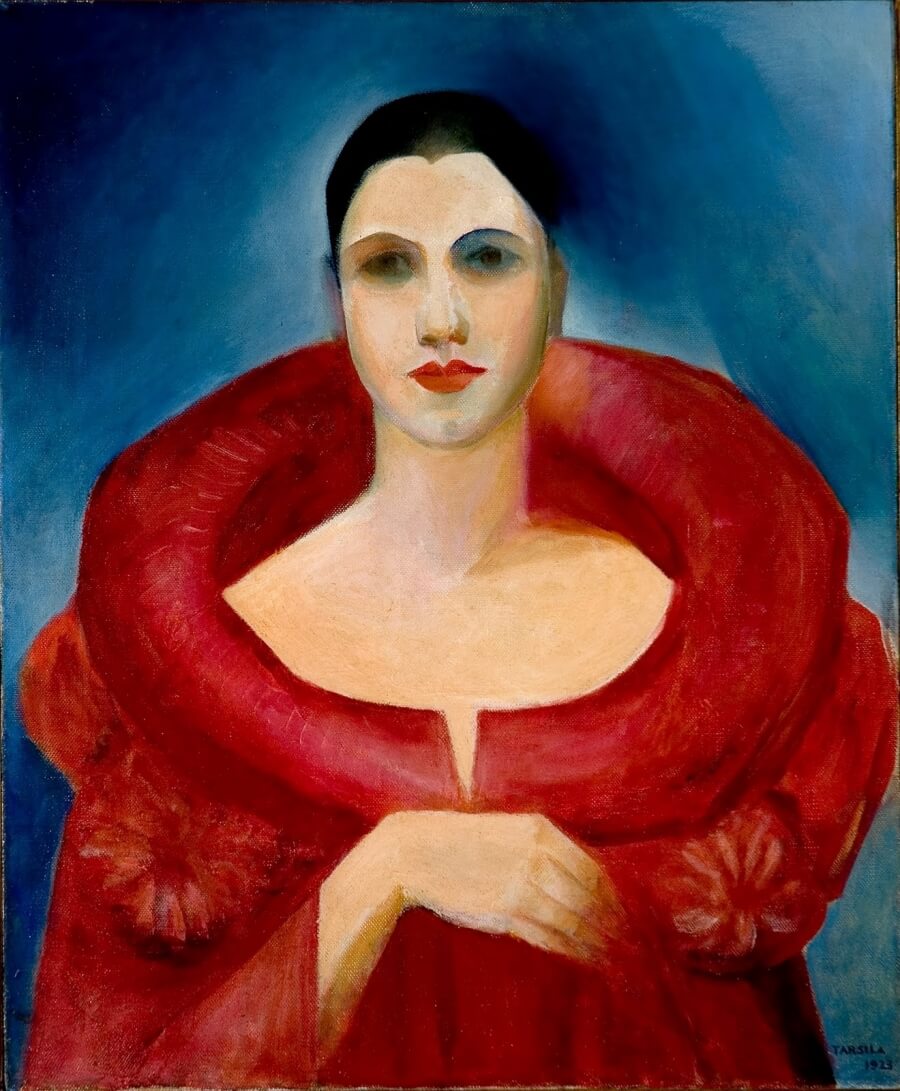

Let’s move on to other comparisons, first with a work by Tarsila herself, as suggested by the curatorship of Tarsila Popular, an exhibition held at MASP, in 2019. At that time, next to A Negra [The Black Woman] there was a self-portrait of the artist born in the city of Capivari (Fig. 2). We are before a white woman with hair and clothing in the transgressive fashion of her time, which were the expression of her individuality, of her adherence to an eminently modern way of life. If we look at A Negra [The Black Woman], however, the situation changes, since both are contemporary compositions, but were made in spirits that were completely different. The dark-skinned character is the construction of a type, an anonymous black woman among many others, a representative whose “simple” existence is characterized by a low capacity for reasoning—small head—and, in contrast, by frequent hard work – gigantic hands, feet and breasts. The absence of clothes is, rather than freedom, the mark of imprisonment in a mythical temporality. This manner of representing those that are subordinated as type also occurred in other artists of São Paulo modernism. If, on the one hand, the historiography of modernism pointed to blacks as an integral part of national culture, on the other hand, it still failed to recognize that inclusion was conducted in ways that often did not coincide with the way these subjects saw themselves or, also, that could not handle the complexity of their cultures, which were reorganized in the new world. Often, what is seen are representations very close to that which we can define as a Brazilian-style tradition, with regard to the representation of black people in this country. From Frans Post to Modesto Brocos, there is a long history. In Portinari’s O lavrador de café [The Coffee Worker], for example, past and present intertwine. Much has already been done, but there is still much more to be done, given the immensity of coffee trees of which we lose sight in the work. And progress, represented by the train, is an indication of a future that lies ahead and that will be driven by the strong arms and legs that carried this country. Something similar also occurs in Tropical, by Anita Malfatti, where we are shown a black/mestizo woman picking/carrying fruits that are symbols of the peculiarity that characterizes life in the tropics. The character is immersed in vegetation—sugarcane and palm trees – that naturalizes her condition. In Samba, Di Cavalcanti advances the stereotype of “mulattas” and samba is composed in this work as a space for debauchery. Black bodies are available for the entertainment of others, whether through music, monopolized by smiling black men, or by the voluptuous bodies of light-skinned black women that, semi-nude, are offered to the spectator.

Legenda

Legenda Tarsila do Amaral. Self-portrait [Manteau Rouge], 1923. National Museum of Fine Arts, Rio de Janeiro.

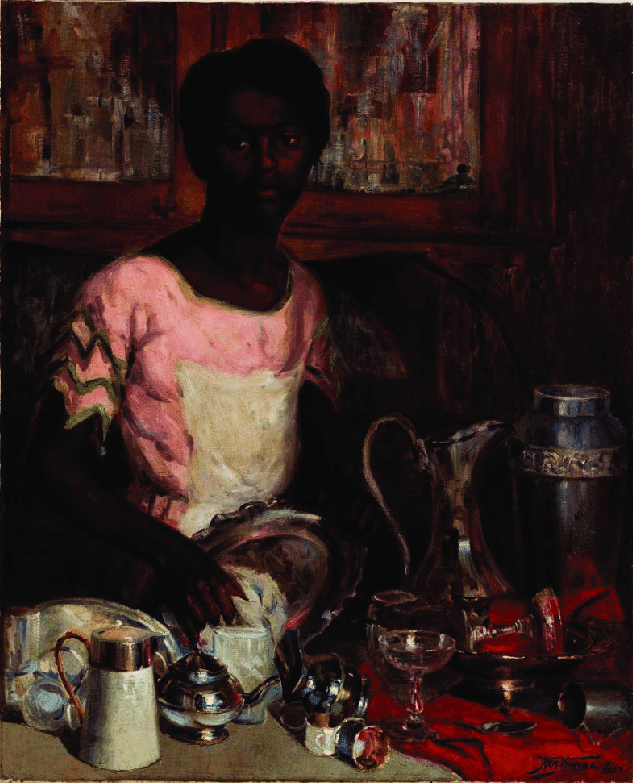

Invariably, white artists—Brazilian or European – have painted black people throughout the history of the country as a type, as bodies that work, or also, as parts of the landscape, but never as subjects endowed with individuality and rationality. And this is independent of the political spectrum that the artist occupied. Let’s look at some more examples. If in A Negra [The Black Woman], the protagonist’s big breast refers to the artist’s notion that “at that time, black women tied stones to their breasts to make them long and they threw them back and breastfed the child they carried on their backs”, Lucílio de Albuquerque’s Mãe Preta [Black Mother] also sacrifices herself by imposition of the system. We catch a glimpse, in this case, of a limit moment, in which the mother, desolate, breastfeeds the master’s son, white, while watching her offspring, abandoned on the floor. There is anguish and inability to act that are recurrent, resembling, accordingly, disparate paintings such as Negres a fond de calle [Negros in the cellar of a slave boat], by Rugendas, and Limpando metais [Polishing Silverware], by Armando Vianna (Fig. 3).

Legenda

Legenda Armando Vianna. Limpando metais [Polishing Silverware], 1923. Mariano Procópio Museum. Juiz de Fora.

Limpando metais [Polishing Silverware], which, apropos, was produced in the same year as A Negra [The Black Woman], is a work in which the artist frames the scene of a snapshot of the daily life of a maid after slavery was abolished. However, the artist does not maintain the same interest he shows in the shiny surfaces of silverware and crockery in the description of the character, who, absorbed in her thoughts, mechanically polishes the metal utensils with care. The rosy hue of the dress recommends a docile femininity. The model also wears a white, immaculate apron and sports straightened hair, in accordance with the aesthetic standard in effect at the time. The girl’s body language, however, is strained, visibly uncomfortable. The bored look is the same we find in Manet’s Un bar aux Folies-Bergère. In both cases, anguish and passivity go hand in hand. And it could not be different, after all they are subjects who were dehumanized by slavery, becoming passive and incapable of acting. Even though they were subjected to injustice, the most they could do was moan and cry softly, just as in Antonio Ferrigno’s Mulata quitandeira [Greengrocer mulatta].

As I mentioned earlier, these images do not necessarily coincide with the projections that these subjects made of themselves. We know this both according to what Social History has shown us since, at least, the 1980s, often in a reading opposite to the sources produced by the constituted repressive powers, and according to what some black artists present to us (CHALHOUB, 1990; REIS, 2003; SLENES, 1994).

We can make a counterpoint, in this aspect. Therefore, let us observe how a black artist contemporary to the modernists of the week of 1922 thought about a similar subject. I refer to the painting Samba no terreiro [Samba in the Terreiro], by Heitor dos Prazeres (Fig. 4). The vegetation that approaches us as spectators gives us the impression that we have entered a secluded world. At the center of the image there are four black persons: two women and two men perfectly symmetrical at the center of the scene. Symmetry is also in the distribution of the colors in their clothes. The two women dance while the men play. Everyone is, probably, wearing their best clothes. The house has a simple constitution, but despite them being poor, everything is portrayed with great dignity. The palm tree indicates that they are in the tropics, but, unlike Tropical or any other painting produced by travelers, it is not a demarcation of the picturesque. We pay attention to the fact that the characters are in a moment of leisure. They have fun and do not have their existence conditioned by the gaze of the other. The women are not half-naked; they all wear shoes and have tiny feet. The symmetry suggests rationality as opposed to the barbarism and dehumanization we have seen on the other paintings.

Legenda

Legenda Heitor dos Prazeres. Samba in the terreiro [Samba in the Terreiro], 1957.

Before Tarsila, another artist, also a black man, studied in Paris and painted blackness. I refer to Arthur Timótheo da Costa. He participated in the Fine Arts Salon with two works, a female nude, entitled Livre de preconceito [Free from Prejudice], and the painting we now see (Fig. 5). Not by chance, his novelty feature caught the attention of critics of his time. Let us see some excerpts:

“Retrato de preto” [Black Man Portrait] is another painting by Thimotheo and one of the best in the Exhibition. As the title says, it represents a black man, with a flat nose and red lips, sucking a cigarette butt. The artist admirably captured the expression of the bold black man of our cities: an expression of audacity and cockiness that is quite characteristic of the “May 13th” (the date slavery was officially abolished in Brazil).

At the current time, could not we dub this painting – O inimigo do argentino [The Argentine’s Enemy]?

Arthur Timotheo boisterously debuted for the general public with a magnificent study of customs entitled “Cabeça de preto” [Black Man Head], exhibited in the 1906 “salon.” Holder of the travel award the following year, with an interesting and well-observed painting entitled “Domingo de Ramos” [Palm Sunday] [sic], he left for Europe and there brilliantly developed the appreciable qualities revealed during his academic apprenticeship.

The term “black” appears in both excerpts and also in another critique, this time from newspaper O Paiz, according to which Arthur Timotheo presented: “o ‘Preto’ incomparável” [The incomparable ‘Black’]. The choice of racial terms—as we well know and according to the abundant bibliography on that—is saturated with significance. According to Gonzaga Duque, the painting depicted “a black man face”. According to the columnist for the Jornal do Commercio newspaper: “His black man head is […] a deeply honest work, of admirable vigor, of a direct and unsurpassed realism, extremely expressive, which alone is enough to honor the young artist’s exhibition”.

The subjects who describe the painting were born and raised under the aegis of slavery and, therefore, knew its significances. It is interesting to note that, even though it is a portrait, the columnists tend to treat it as a “type,” usurping his individuality, so to speak. In the first excerpt, the journalist comments, in addition to the character’s facial features, on his idleness. Why would he be audacious and cocky? What is transgressive about this portrait?

Arthur sheds light on the face of a middle-aged man. He is smoking with his eyes turned to the ground, hiding part of his face with a long hat with a narrow crown. The man has a carefree face and thrusts his jaw forward as he purses his lips to puff. The image, unlike the previous cases, makes it quite clear that the scene takes place during the day, in an outdoor setting. This is yet another non-threatening figure, although the columnist, in his usual prejudice, takes him as some “May 13th”, someone “bold.” The use of colors unequivocally announces: the so-called “black” is the synthesis of Brazil.

If we juxtapose the works of Arthur Timótheo da Costa and those of Tarsila do Amaral and understand that the modern lies in the approximation to European avant-gardism and that the deconstruction of form is its point of maximum expression, it becomes easy to obliterate the first from this narrative. However, the novelty of the modern consists in the use of politics as an opportunity for artistic creation. What motivated the Impressionists to create from other bases has to do, above all, with the mundane transformations . The bourgeois revolution and the industrial revolution were, therefore, fundamental in this process. We need to closely examine Brazil’s representative tradition to realize that painting a black man in a credible way in 1906 is truly revolutionary, insofar as he was often absent from this place of humanity throughout the history of national art.

As we can see, the way Heitor dos Prazeres and Arthur Timótheo da Costa advance regarding the representation of black people is constituted on other bases. Both—each in their own way—were, for a long time, on the sidelines of the narrative of the white-Brazilian art. The dynamics of Brazilian-style racism subordinated their respective productions to the same extent that it brought into prominence not only A Negra [The Black Woman] but several other paintings produced by São Paulo modernism as a new paradigm in Western art. That only started to be questioned vehemently at a time when, in a global context, the Brazilian racial paradigm was radically changed. Estrangement is a sign that we live in new times. Europe becomes provincial and A Negra continues to be seen, but for different reasons than when it was created.

Legenda

Legenda Arthur Timotheo da Costa. Black Head, 1906. Afro-Brazil Museum.

References

AMANCIO, Kleber Antonio de Oliveira. 2021. A História da Arte branco-brasileira e os limites da humanidade negra. Revista Farol, v.17, n.24 (Setembro), 2021, 27-38. https://doi.org/10.47456/rf.v17i24.36351

AMARAL, Aracy. 2003. Tarsila e seu tempo. Editora 34/ EDUSP. São Paulo.

BITTENCOURT, Renata. Outras negras. In: Tarsila Popular [catálogo da exposição]. São Paulo: MASP, 2019.

CARDOSO, Renata Gomes. A Negra de Tarsila do Amaral: criação, recepção e circulação. VIS Revista do Programa de Pós-graduação em Arte da UnB, v.15, nº2 (julho-dezembro), 2016, 90-110. https://doi.org/10.26512/vis.v15i2.20394

CHENG Anne Anlin. Second Skin: Josephine Baker & the Modern Surface. New York: Oxford Univeristy Press, 2010.

CHALHOUB, Sidney. Visões da liberdade: uma história das últimas décadas da escravidão na corte. São Paulo, Companhia das Letras, 1990.

CHRISTO, Maraliz de Castro Vieira. Algo além do moderno: a mulher negra na pintura brasileira no início do século XX. 19&20, v.4, n. 2, (Abril), 2009. http://www.dezenovevinte.net/obras/obras_maraliz.htm

DOMINGUES, Petrônio. A “Vênus negra”: Josephine Baker e a modernidade afro-atlântica. Estudos Históricos. v.23, 45. 95-124 (Junho), 2010. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-21862010000100005

FERREIRA, Thaís dos Reis. A negra: Diálogos entre a obra de Tarsila do Amaral e o feminismo negro. TCC de Especialista em Mídia, Informação e Cultura. ECA-USP, 2017.

LEININGER-MILLER, Theresa. New Negro Artists in Paris: Africana American Painter and Sculptures in the City of Light, 1922-1934. New Brunswick, New Jersey and London: Rutgers University Press, 2001.

MEIRA, Silvia. “A Negra” de Tarsila do Amaral: escuta da condição da afrodescendente na formação do povo brasileiro”. Comunicação apresentada no XVIII CBHA. Florianópolis, 2018.

MUSEU DE ARTE ASSIS CHATEAUBRIAND. Tarsila Popular / Organização editorial e curadoria Adriano Pedrosa, Fernando Oliva; textos Adriano Pedrosa [et al.]. São Paulo: MASP, 2019.

OLIVEIRA, Cláudia de. “Corpos pulsantes: ‘A Carioca’ de Pedro Américo e ‘A Negra’ e ‘Abaporu’ de Tarsila do Amaral”. Journal of Iberian and Latin American Research, v.20, n.2 (Agosto), 2014, 254-266

REIS, João José. Rebelião escrava no Brasil: a história do levante dos Malês em 1835. São Paulo, Companhia das Letras, 2003.

RIBEIRO, Leo Gilson. Entrevista com Tarsila do Amaral. Revista Veja, 23 de fevereiro de 1972 – Edição 181, 1972.

SIMIONI, Ana Paula Cavalcanti. Modernismo brasileiro: entre a consagração e a contestação. Perspective, n. 2, 2013. https://doi.org/10.4000/perspective.5539

SLENES, Robert. Na senzala, uma flor: esperanças e recordações na formação da família escrava – Brasil Sudeste, século XIX. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 1999.

SMALL, Irene V. Plasticidade e reprodução: A Negra de Tarsila do Amaral. In: Tarsila Popular [catálogo da exposição]. São Paulo: MASP, 2019.

SWEENY, Carole. La revue negre: negrophilie, modernity and colonialism in Inter-war France. Journal of Romance Studies, v.1, n.2, 1-14, 2001.

VIDAL, Edgard. Trayectoria de una obra: “A negra” (1923) de Tarsila do Amaral: Una revolución icónica. Artelogie, v 1. n.1. (Março), 2011. https://doi.org/10.4000/artelogie.8562