Learning to inscribe without scribing

To discover the first productions in visual arts made by black Brazilian women with authorship. To identify the materialities and languages accessed and mastered by those visual artists. To reflect on the thematic approaches they contributed based on their experiences, their trajectories, their contexts, their ancestry. To collect information that supports a comprehensive reading of these women artists and their productions, related to the conditions of their creation processes according to their informal, non-formal and formal education. To validate testimonies from their circle of relatives and close acquaintances that are linked to oral tradition as an unquestionable source of research. To find artworks by these visual artists in private and public collections.

These are the goals and methodology of our research on female visual artists of black African descent in Brazil. Phenotypically black, they had different backgrounds that coincide in the decisive mark of family education as a heritage that contributed to the development of the skills and dedication they applied to visual arts.

Giving visibility to these visual artists implies, foremost, understanding the challenge of having access to documents that would make it possible to unearth biographical information about creative processes and the works resulting from them.

In the meantime, accumulating documentation based on material resources is not central to the narratives of populations that distribute that role among other intangible historical sources such as speech, dance, ceremony, ritual, ways of doing and living, areas that enjoy the same legitimacy as testimonies about the past. This aspect is key to the so-called “clash of narratives” that is set to intensify in 2022 with the events celebrating and reviewing the Modern Art Week of 1922; however, we prefer to replace the term that presumes that one side will win while the other will lose with “coexistence of narratives.”

That said, writings on black women in the field of visual arts are guided by other factual elements that go beyond academic rigor as a universal assumption. Grada Kilomba analyzes universality as a category that suppresses a notion of black humanity and, consequently, the acknowledgement of other paradigms of research:

(…) the center to which I refer here, i.e., the academic center, is not a neutral place. It is a white space where the privilege of speech has been denied to black people. Historically, this is a space where we have had no voice and where white female and male scholars have developed theoretical discourses that formally construct us as the inferior “Other,” placing female and male Africans in a position of absolute subordination to the white individual. In this space we have been described, classified, dehumanized, primitivized, brutalized, killed (HALL/KILOMBA 2019, p. 50-51).

The criticism of supposed universalism as a south-up concept of academic research extends to objectivity and neutrality, forming a triad of white quality control over research. Well then: we renounce them, since they subscribe to a property regarding a true and proper way of how to present, appreciate, research, narrate, criticize in visual arts, since such conceptualizations function much more as a filter of what is included in history than structuring and impartial concepts of writing mechanisms.

We are interested in scrutinizing the creation processes of these women, not only those related to their works, but also to them as visual artists, considering the social contexts in which they were situated, which reserved fixed roles to be played by women of the African diaspora, largely related to the images of control explored by Patricia Hill Collins.

Ana das Carrancas (1923-2008), Madalena dos Santos Reinbolt (1919-1977), Raquel Trindade de Souza (1937-2018), born in places that are geographically distinct yet similar in terms of the learning acquired through informal education provided at home; learning that served as school and university for the apprehension of languages, techniques, themes, concepts and poetics which inscribe their actions in ways of existence that re-enact the world systems of African peoples in Brazil.

These are trajectories with their singularities, with informal education as a converging point of the experience of artistic training that included ancestral technologies and epistemologies learned from family members and communities. Historically questioned by means of formal education as to their legitimacy, these forms of knowledge constitute an educational system with an ontological and cosmological foundation that borders the artistic and aesthetic and which is subtracted when faced with the curricular knowledge deemed erudite.

In this sense, simultaneously, as curatorship is a decisive and determining practice in the construction of visual arts narratives, we claim that it is ethical to exercise it based on the multiplicity of art as a professional activity; of the object stemming from its stages; of the person behind the visual arts professional who is alert to the rotation of agents in the exercise of power..

Ana das Carrancas:

Giving birth to the dream through clay

“My blood is black, but my soul is made of clay” is one of the many sayings of Ana Leopoldina dos Santos, which links her physiologically and spiritually to clay. Born in Santa Filomena, district of Ouricuri, a town in the arid region of Araripe, in the state of Pernambuco, she first handled clay as a child, influenced by her mother, Maria Leopoldina dos Santos, a crockery maker. She became a potter and also sold a number of utensils produced by the family.

The visual artist sought the raw material for her pieces in the São Francisco River, while incorporating fantastic, mystical and artistic elements present in the regional culture. Contact with numerous thought-provoking reports about the figureheads of the vessels that navigated the river stimulated her imagination and guided her pottery production, which in the 1960s developed from functional to poetic:

[…] When looking for raw material for her pieces on the banks of the São Francisco River, Ana created her first “gangula,” a small ceramic vessel, similar to a medium-sized vase, with a figurehead on the prow (GUALBERTO, 2017, p.2).

Ana’s first figureheads emerged from the gangulas. About these sculptures that populate the tradition of navigators, the researcher Rosélia Sampaio de Miranda says:

The figureheads of the São Francisco River were at first considered sculptures on the bows of vessels […] they protected the vessels and their crews against possible difficulties during the trip (MIRANDA, 2019, p.2).

The figureheads bring together conceptual, symbolic, spiritual and formal characteristics that give them a syncretic and dynamic nature. We found several populations that, in different parts of the world, believed in the supernatural power of figureheads, or similar objects, to protect crews and ward off harm when dealing with the personalities that inhabit the waters, in addition to placating the moods of seas and rivers.

In the São Francisco River region, and in the cultures of riverside populations in general, there survives a rich mythological repertoire that is syncretized with the belief in the Catholic God as protective deities. For such communities, many are the magical beings that inhabit the river waters and must be considered and/or revered with the aim of ensuring calm waters for navigation, such as the Minhocão, Surubim-Rei, Bicho d’Água, Cachorro d’Água, Cavalo d’Água, Capetinha, Galo Preto, Angaí, Anhangá and Goiajara (VALADARES/ PARDAL/ MIRANDA, 2019).

One of the first riverhead artists of the São Francisco River region of which we have information is Francisco Biquiba dy Lafuente Guarany (1884-1985), who learned from his father the trade of joiner and carpenter.

Ana Leopoldina was first noticed by technicians from Fundarpe (Pernambuco Historical and Artistic Heritage Foundation), who admired the quality of her pieces and commissioned her to make miniature figureheads to be given as souvenirs at the inauguration of the Municipal Library of Petrolina (GUALBERTO, 2017).

Stylistically, her figureheads did not reproduce the aggressive and/or fearsome expressiveness that we find in this tradition in the São Francisco River, as their anthropo-zoomorphic features depicted a fixed and serious facial expression: lips slightly inclined downwards, flared nostrils and large eyes with a small orifice in the center, directed towards the horizon. This formal solution, which characterizes the look of the figureheads and of that face replicated in other objects, emerged as an ex-voto of Ana das Carrancas: if José Vicente, her companion deprived of the sense of sight, no longer needed to beg to support the family, Ana would “pierce” the eyes of all her clay pieces (GUALBERTO, 2017, p. 3).

Developing a unique style in the art of ceramics brought renown and money to Ana das Carrancas, realizing her dream of providing her family with material conditions to live with dignity.

The “Clay Lady,” a worthy nickname, died at the age of 85, in 2008. Those interested in learning about her art and career can visit the Ana das Carrancas Art and Culture Center, maintained by the Municipal Government of Petrolina, with the effective presence of her daughters who, being potters also, consolidate three generations of women in the art of clay, whose informal knowledge was decisive in the development of their destinies, especially the unique inventiveness of Ana das Carrancas.

Legenda

Legenda Ana das Carrancas, undated. Source: https://anadascarrancas.wordpress.com/ana-das-carrancas/

Madalena dos Santos Reinbolt:

The dream through many threads

An excellent portrait of Madalena dos Santos Reinbolt’s childhood, in Vitória da Conquista, Bahia, is afforded by her works, which we consider unclassifiable within preexisting artistic schools and exquisite regarding the composition and language of the weaving that made her famous. In her works, initially produced in oil, we find the abundance of farm food, the exuberance of nature modified by agriculture, the diversity of domesticated fauna, community celebrations, life in a rhythm ordered by hours ruled by the courses of the sun and moon.

She came from large family of 21 siblings. In learning about her daily life—the matriarch woke up at four in the morning to start her chores—we realize the amount of technical knowledge required to maintain a medium-sized farm. Her father and mother ran the farm, raising and fattening livestock for produce and sale; growing rice, beans and corn; making butter, smoking and preserving meats, which shows a certain abundance. She was aware of the technical knowledge of her roots, especially of her mother, which we note when she talked about her upbringing:

My father was a farmer. My mother made clay crockery, linen, blankets, spun cotton and made clothes for the whole house. Bedclothes, bags, suits for my brother, bedclothes for us, many things. She would get up at 4 am and hand spin cotton into yarn, yes, she did it herself, Ana Maria de Souza Pereira, and then she would have it woven on the loom (REINBOLT/FROTA, 1975, p. 114).

This specific knowledge for the fulfillment and maintenance of a routine that provided subsistence and survival had also an aesthetic side that was expressed in the shaping of domestic utensils; in the interweaving of the lace designs; in the sewing of garments; all activities performed by her mother. All of this was absorbed by Madalena dos Santos, who as a child painted on newspaper and extracted the juice of the plants to use as paint on paper (FROTA, 1975).

Around the age of 20 she migrated in search of financial independence, passing through Salvador, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro before finally settling in Petrópolis in 1949 (FROTA, 2005). There are controversies about her occupation at Fazenda Samambaia, owned by the architect Lota Macedo Soares and the writer Elizabeth Bishop, but all evidence suggests that she was a cook, and that her husband, Luiz Augusto Reinbolt, whom she married in 1952 and who gave her the German surname, was the caretaker.

On noticing her artistic gifts, Lota and Elizabeth urged her to paint consistently, which she did from 1950 onwards. However, in the other households where Madalena worked, in between her domestic chores, she embroidered, confirming a vital imperative of her creative streak:

(…) sitting on her bed, with the 154 knitting needles inside a basin, on a stool beside her (…). Her employers allow her to sell the rugs in this country house where there are works of hers on the wall, owned by the family (FROTA, 1975, p. 123).

We observe that her career was now encouraged, now hindered by the people who employed her. Without physical freedom for not having gathered the resources to have her own home and, therefore, her own studio, Madalena dos Santos Reinbolt found refuge in her inventions.

About her creative process, she conceived the compositions in her mind, without previous study: “I do it in thought. I can already see it even with my eyes closed […] I write whatever comes to my mind. I go on making the planets in my head” (FROTA, 1975, p. 114).

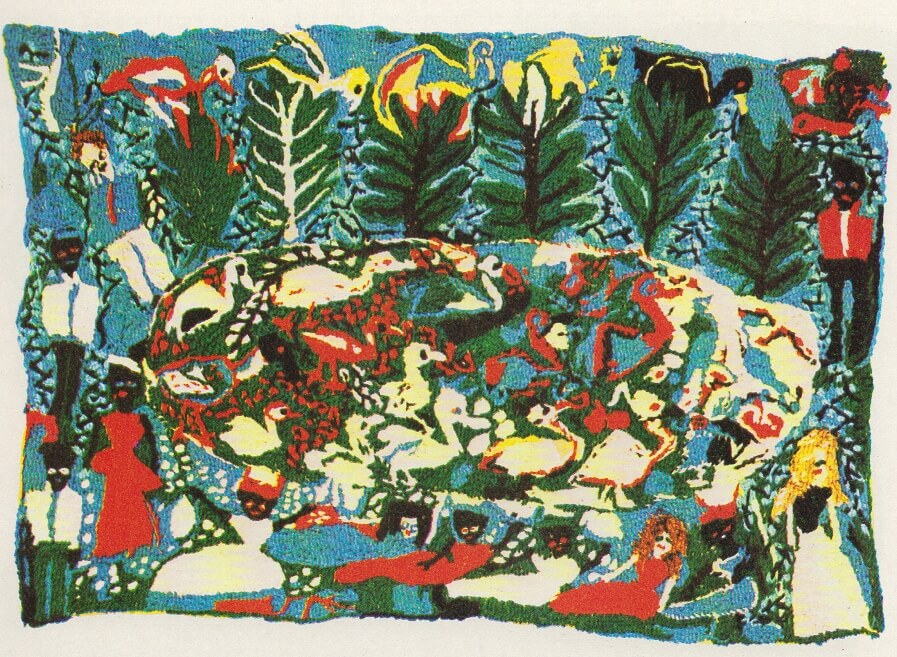

In her works, there is intimacy in the relationships between colors that is enhanced by the fact that all the represented elements share the same plane, without the canonical composition that distinguishes figure and background in the composition.

In the hierarchy of techniques and languages in the field of fine arts, embroidery and/or tapestry do not occupy a prominent position, which gives works made in those mediums the controversial status of crafts or applied arts. Since the Renaissance, they have been considered minor arts and skills deemed desirable for women brought up to marry, raise a family and run the household; changes in this sense emerge with the Industrial Revolution, the advance of textile markets and the renewed appreciation of manual craftsmanship as a premise of the Arts and Crafts movement (SIMIONI, 2009).

Intuitively, Madalena subverted this social expectation by giving another purpose to the technique learned from her mother. If for her mother sewing and embroidering were no more than domestic chores, for Madalena their use was inventive and artistic. In the same period in which she moved from painting to wool yarn, in the early 1970s, feminist visual artists also took to so-called feminine textile practices aiming to challenge the canons, the male and white status attributed to professionalization in the visual arts, giving a political stance to the uses of language:

A third moment in the relationship between arts, textiles, especially embroidery, and the issue of gender occurs from the 1970s onwards, in the USA, with the advent of feminism. It is no longer about accepting the dominant artistic hierarchies and striving to integrate textile works, seen as essentially female, within the dominant field, but doing something more daring: subverting the canon (SIMIONI, 2009).

The incorporation of technologies previously relegated to women in the field of artistic creation as a liberal feminist strategy is contemporary to the debate on black feminism in Brazil, led by Lélia Gonzalez at the time. Her studies denounced the underemployment of black women, showing that 83% of them did manual labor, concentrated in agricultural regions and in the provision of services in urban centers (Gonzalez, Lima and Rios, 2020). This picture partially explains Madalena dos Santos Reinbolt’s modest financial returns as a visual artist during her lifetime, as it intersects her condition of existence in relation to the visual arts paradigms established in the categories of class, race and region.

Unlike Ana das Carrancas and Raquel Trindade de Souza, Madalena dos Santos Reinbolt did not have any offspring, which affects the preservation of her legacy and memory.

The textile artist deserves a thorough investigation of her existence and persistence to be understood as a visual artist, despite the aforementioned circumstances. Her insertion in posthumous historiography, with the participation in the Venice Biennale in 1978, studies of her work in several art books and, gradually, a re-education of critics to acknowledge the unique quality of her tapestry of dynamic, colorful and unprecedented composition in Brazilian art, is still timid.

Otherwise, artists like Madalena dos Santos Reinbolt will remain dwarfed by subcategories of art that determine the visibility, marketing and historicization of productions that are contrary to current canons. Proper criticism of work like hers sabotages the crystallized castes in the artistic field and honors the visual arts as a creative expression intrinsic to all humanities.

Legenda

Legenda Madalena dos Santos Reinbolt, undated. Source: FROTA, Lélia Coelho. Mythopoetics of 9 Brazilian artists. Rio de Janeiro: FUNARTE, 1978.

Legenda

Legenda Madalena dos Santos Reinbolt. March Lagoon, 1974. Source: FROTA, Lélia Coelho. Mythopoetics of 9 Brazilian artists. Rio de Janeiro: FUNARTE, 1978.

Raquel Trindade de Souza:

The dream is now

Pernambuco is one of the first cradles of the Afro-Brazilian population, the place where the first Bantu ethnic and cultural groups landed from Africa. Roughly speaking, Bantu is to the cultures of this continent as Latin is to Europeans. It is not restricted to a language branch, expanding to sociocultural values shared by populations that are distributed across Central Africa. In addressing the multi-artist Raquel Trindade de Souza, eldest child of the poet Francisco Solano Trindade and the occupational therapist Maria Margarida Trindade, a preamble is in order to situate the family’s origins and the African ancestry rooted in them.

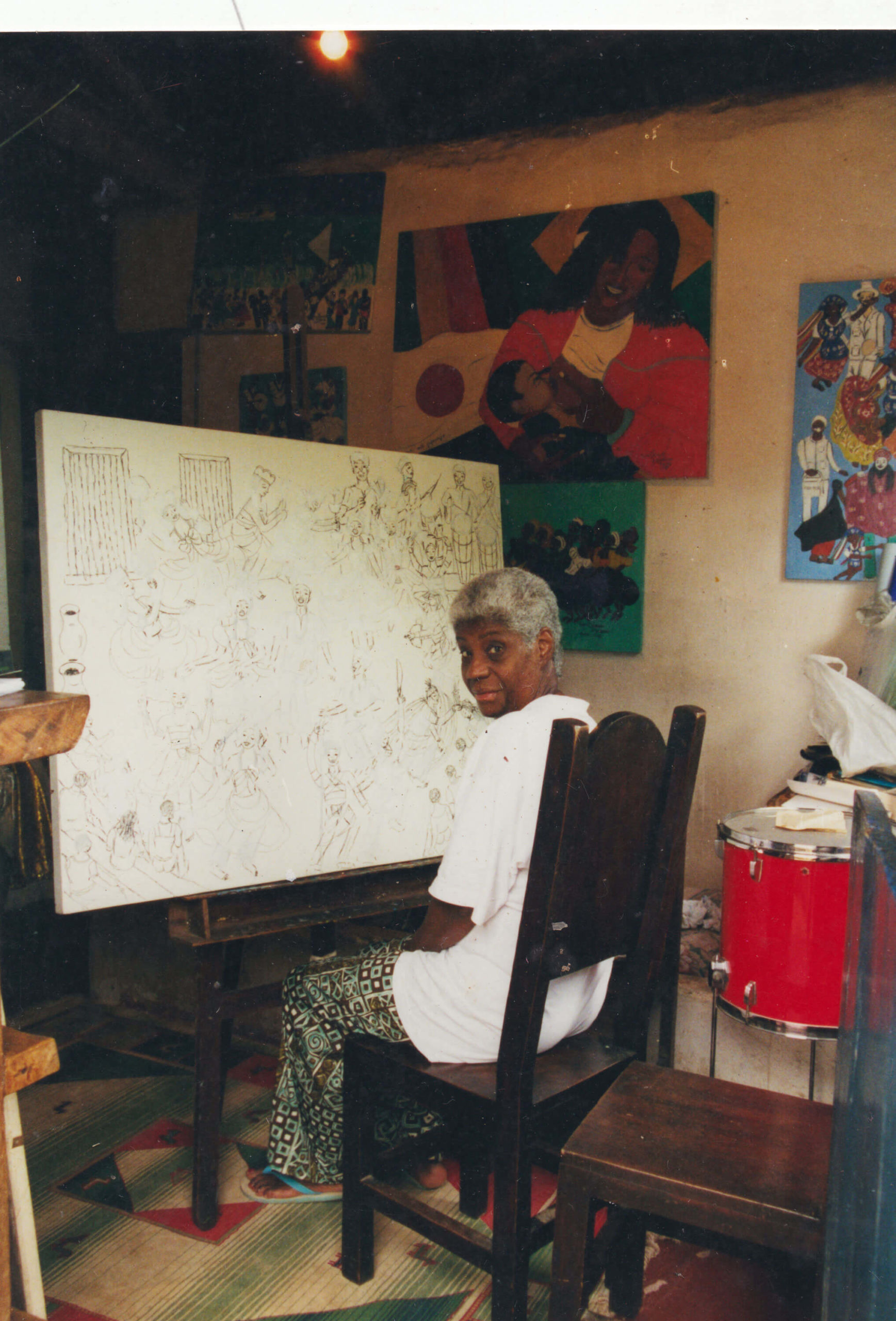

Born in Recife, Raquel Trindade was raised in a culturally diverse environment, which provided different kinds of learning, evidenced by her professional occupations. Unlike her previously introduced contemporaries, her family was guided by African civilizational values, disseminating class and race consciousness among the black communities among which they lived.

Her mother and father hosted meetings of the Communist Party at home and Solano Trindade founded Frente Negra Pernambucana (Pernambuco Black Front) in Recife in the 1930s. In other words, the family’s awareness of their social status was combined with tactical activism.

In the following decade, the Trindades settled in Rio de Janeiro. Raquel’s father, who was already an author at the time, became a popular figure among intellectuals and artists who frequented the famous “Vermelhinho” bar (TRINDADE, 2008). Raquel Trindade accompanied her father on his incursions through the city, which allowed her to interact with personalities of great importance for the edification of Afro-Brazilian culture, as is the case of the dancer Mercedes Baptista, a pioneer in the research and convergence of choreographic elements present in the rites of the Orishas with classical ballet, or the conductor Abigail Moura, who lead a similar operation in the field of classical music, creating the Afro-Brazilian Orchestra.

The painter Raquel was also strongly influenced by artists who lived in or visited Embu das Artes, since the Trindades moved to that region in the 1960s. People of different origins, including foreigners, used different techniques, from two-dimensional to three-dimensional, in the production of their works and were inspired by dialogues provided by this environment. Among them is the Silva family, to which belonged Maria Auxiliadora and her brother Vicente Paulo, one of Raquel Trindade de Souza’s partners.

This profusion of cultural professionals around the historic center of the old Aldeia de M’Boy made up the incipient collective of the art fair that is still held on weekends in the town, similar to the Art Fair of Praça da República, in downtown Sao Paulo.

In the 1970s, along with the fundamental initiatives of fairs as a resource for the exhibition and sale of works by artists on the margins of hegemonic cultural institutions, at least three groups of artists, historically classified as naïf, interacted and stimulated more committed studies about this circulation: the so-called “Osasco group,” which aimed to document the culture of the interior of the state of São Paulo; the group of migrant artists from the Northeast region; and the previously mentioned group of Embu das Artes (FROTA, 1975).

The painter Raquel was nurtured politically by these movements of artists who forged their professionalization through less systematic and excluding means, and artistically by art workers endowed with courage and authenticity who invented ways to live off art by drawing on a profusion of pulsating styles embedded in a different system of the visual arts.

At first, her oil paintings related to Afro-religious themes, evoking funeral stone ornaments that record and orally spread the stories of the Orishas. “Kambinda,” as she liked to be called in allusion to the matrilineal Cabinda nation from Angola (SANTOS, 2021), strongly objected to having her works branded as naïf: “In painting, I do not like to be called naïf or primitive, my painting is Afro-Brazilian” (TRINDADE, 2013, p. 59).

Raquel Trindade de Souza fluidly developed her work as a painter in Embu das Artes, alongside with all the other occupations that made her famous. She passed away in 2018 following a surgery, and her funeral brought together several groups of the tradition at Teatro Popular Solano Trindade, which she managed in honor of her parents. In 2021, the individual exhibition Ocupação olhares inspirados: Raquel Trindade, rainha Kambinda [Inspired Gazes Occupation, Queen Kambinda, in São Paulo, spanned decades of her paintings, gathering works and resources that offered the public a full understanding of her cultural heritage.

Legenda

Legenda Raquel Trindade de Souza, undated. Trindade’s Family Collection

Dreams dreamt by our ancestors

Knowing these narratives means affirming that there are black women who are protagonists in the visual arts and that such stories must be recorded and analyzed based on different paradigms, stimulating the expansion of the process of revising how visual arts are seen.

Naturalizing discourses on black realities is a process of decolonizing the gaze, the mind, the taste, which are retrained to see the artistic object from an original, creative, intimate point of view, which unveil “the female subject” to understand how she uses art to support the legitimate and political right of existences that must be appreciated, listened to, apprehended through the lens of the adoption of other ways of being. We are in the full process of breaking with the coloniality of creating.

References

Ana das Carrancas. Centro Cultural Ana das Carrancas. Available from: https://anadascarrancas.wordpress.com/ana-das-carrancas/https://anadascarrancas.wordpress.com/ana-das-carrancas/. Access on: 28 fev. 2022.

COLLINS, P. H. Pensamento feminista negro: conhecimento, consciência e a política do empoderamento. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2019.

FAJARDO-HILL, C. Mulheres radicais: arte latino-americana, 1965-1980. Curadoria Cecilia Fajardo-Hill, Andrea Giunta. São Paulo: Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, 2018.

FREIRE, M. S. L. KILOMBA, Grada. Memórias da plantação: episódios de racismo cotidiano. Rio de Janeiro: Cobogó, 2019.

FROTA, L. C. Mitopoética de 9 artistas brasileiros: vida, verdade e obra. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Fontana, 1975.

FROTA, L. C. Pequeno dicionário do povo brasileiro – século XX. Rio de Janeiro: Aeroplano, 2005.

GUALBERTO, T. Ana das Carrancas, a Dama do Barro. São Paulo: Museu Afro Brasil, 2017. Available from: http://www.museuafrobrasil.org.br/docs/default-source/publica%C3%A7%C3%B5es/gualberto-tiago-ana-das-carrancas.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Access on: 28 feb. 2022.

GUERRILLA GIRLS: gráfica 1985-2017. Curadoria Adriano Pedrosa, Camila Bechelany. São Paulo: MASP, 2017.

HERKENHOFF, P. Invenções da mulher moderna: para além de Anita e Tarsila. Curadoria Paulo Herkenhoff. São Paulo: Instituto Tomie Ohtake, 2017.

HERKENHOFF, P.; HOLANDA, H. B. de. Manobras radicais. Curadoria Paulo Herkenhoff, Heliosa Buarque de Holanda. São Paulo: Associação de Amigos do Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, 2006.

MALUNGUINHO, E. Erica Malunguinho, na luta contra o racismo e o patriarcado. [Entrevista cedida a] Taís Ilhéu. Acervo Online. Le Monde Diplomatique Brasil, 19 dez. 2018. Available from: https://diplomatique.org.br/enquanto-nao-houver-emancipacao-para-os-que-estao-ainda-negociando-a-vida-nao-havera-para-ninguem/. Access on: 28 feb. 2022.

MESTRE GUARANY. In: ENCICLOPÉDIA Itaú Cultural de arte e cultura brasileira. São Paulo: Itaú Cultural, 2022. Available from: http://enciclopedia.itaucultural.org.br/pessoa216535/mestre-guarany. Access on: 28 feb. 2022.

MIRANDA, R. S. de. O desenho das carrancas e seus significados. In: XIV SEMINÁRIO DE DESENHO CULTURA E INTERATIVIDADE, 14., 2019, Feira de Santana. O pensar desenho: reflexões culturais e interdisciplinares. Feira de Santana: UEFS, 2019.

MULHERES ARTISTAS: as pioneiras (1880-1930). Curadoria Ana Paula Simioni, Elaine Dias. São Paulo: Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, 2015.

PEDROSA, A.; RJEILLE, I.; LEME, M. (org.). Histórias de mulheres, histórias feministas. São Paulo: MASP, 2019.

SANTOS, R. A. F. dos. Saudação à Rainha Kambinda. In: FELINTO, R. Olhares inspirados: Raquel Trindade – Rainha Kambinda. São Paulo: SESC 24 de Maio, 2021. p. 14-23. Available from: https://issuu.com/sesc24demaio/docs/folder_olhares_issuu-menor. Access on: 28 fev. 2022.

SILVA, E. C. da; FELIPE, D. A. Tapeçarias de Madalena dos Santos Reinbolt: identificação de arte e artista popular. Conhecer: debate entre o público e o privado, v. 9, n. 23, p. 94-123, 2019.

SIMIONI, A. P. C. Nas tramas do gênero: os bordados nada femininos de Rosana Paulino e Rosana Palazyan. ANPOCS, Caxambu, 2009. Available from: https://www.anpocs.com/index.php/papers-33-encontro/fr/fr07/2237-fr07-anapaulasimioni/file. Access on: 28 fev. 2022.

SOUZA, R. T. de. Raquel Trindade – a Kambinda. In: Mulheres negras contam sua história. Prêmio Mulheres Negras contam sua História. Brasília: Secretaria de Políticas para as Mulheres, 2013. p. 46-61.