Although there are different meanings of what Natural History is or was, in general, when considering what it meant during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, it refers to the corpus constituted by the early ideas shared by taxonomy, botany, geology and zoology, with a clear concern for the study, order and organization of nature. It is generally associated with the ideas of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, which advocated for an experiential knowledge, and therefore implied knowing, exploring and investigating nature in a direct way.

This thinking fostered both explorations of territories and experiments with the elements of nature (including human beings). It is also a framework of thought associated with the expansion of empires such as the British and French empires in the Americas, Asia and Africa. Natural History thus implies an exploratory, ordered, systematic and hierarchical knowledge of nature, where Europe is constituted as the organizing center of ideas and gatherer of the knowledge produced in the periphery through the multiple scientific explorations that were happening.

In those explorations, race is an ideological and scientific construction that gives legitimacy to the hierarchization of human differences, a process of elaboration in which visual culture played a core role. David Bindman, Brian Wallis, and Adrienne Childs and Susan H. Libby (2002) acknowledge that there is a transmission of ideas from the then emerging Taxonomy to the aesthetics of beauty. In this sense, visuality is a field that gathers discourses from Natural History and Taxonomy, and constructs human differences as scientific and social, racial and visible truths. Simultaneously, decolonial theory reveals close connections between the intellectual exercise, strengthening and support of the enlightened elites, and modeling of the social apparatus as a reflection of these socio-racial hierarchies (SILVA, 2002).

The visual culture of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was part of this moment of “scientific” otherness, construction of nature-other, and also included the construction of humanity-other. In other words, while social sciences such as Anthropology were consolidated bound to colonialist geographical exploration, advances in fields such as photography were instrumental in the recording of these humanities-others in overseas territories, invoking their faithful record of “reality”. Even in 1852, the British Association for the Advancement of Science published its Manual of Ethnological Enquiry, in which photography was recommended as an objective method to obtain images identical to the original” (BALANTA RODRÍGUEZ, 2012). Additionally, engraving and photography became the mechanisms to substantiate a sort of imperial pride associated with travel, while constituting a scientific proof of the inferiority of those in the colonies (BALANTA RODRÍGUEZ, 2012). This early association of science, geographical exploration and visual culture drove the construction of colonialist ideologies in the mid-nineteenth century (ROGERS, 2006).

The ideas of the overseas lands inhabitants that reflected animalistic, monstrous or diabolical values and behaviors, are documented in painting and drawing handbooks as early as in the sixteenth century. At that time, the handbook Iconología (Iconology) by Cesare Ripa recommended the allegories corresponding to Africa to be represented showing its “scarcity of resources”. The handbook associate it with that allegory devoted to Lust (RIPA, 1593). By the eighteenth century, drawing handbooks such as that by the physician Petrus Kamper (1795), and the images in texts by the German physiognomist Johann Caspar Lavater (1775-1778), proposed an evolutionary classification of the dimensions of the skull of different ethnic groups, in clear synchronization with the systematic and hierarchical ideas of Natural History (BINDMAN, 2002). Those considered to be African were closer to the monkey, while the whiter ones were closer to the “ideal” of male beauty, identified as the Apollo of Belvedere.

Such association between science, aesthetics, visual culture and geographic exploration was materialized in extensive projects funded by banks, governments, and powerful university institutions, among others. This article reviews the representations of black women in two of these major projects: The Chorographic Commission led by Italian geographer Agustín Codazzi, carried out in present-day Colombia; and the Thayer Expedition, led by the Swiss naturalist Louis Agassiz, and that took place in Brazil. Both projects show how powerful and persistent the dehumanization of black women’s bodies can be when it is invested with a scientific character, although these images per se do not constitute scientific objects (ROGERS, 2006). Rosana Paulino, an Afro-Brazilian artist, reacts to the dehumanization reported by the Thayer Expedition by creating her powerful series Assentamentos (Fig. 7 and 8). Meanwhile, Liliana Angulo finds in a portrait of Henry Price, part of the Corographic Commission images, a reason to produce a Portrait of Lucy Rengifo that recreates the dignity so denied in the remaining images que that are part of this project.

A review of the aforementioned scientific projects leads us to consider a series of aspects that evidence the hierarchical relationships of those involved in the production of visual objects. Both projects are headed by white European men, whose prestige ensures them the economic backing of nascent governments and educational institutions in the Americas. Both Codazzi and Agassiz were educated and part of a broad scientific network that replicated the socially, geographically and politically hierarchical ideas that would mature into what came to be known as scientific racism. In this sense, images also followed a pattern that replicated such hierarchies, in their production, circulation, regulation, identification and representation of human differences (HALL, 1997). That is to say, black women’s representation is affected by the hierarchy of who commissioned the images, by the use they were given at the time, by the intentionality of the production itself, and by the audience that would read them. It is worth asking whether this circuit, as Hall presents it, may be altered over time; whether it is possible, as the artists propose, to intervene these works constructed in other times and under other ideals, in order to affect their contemporaneity.

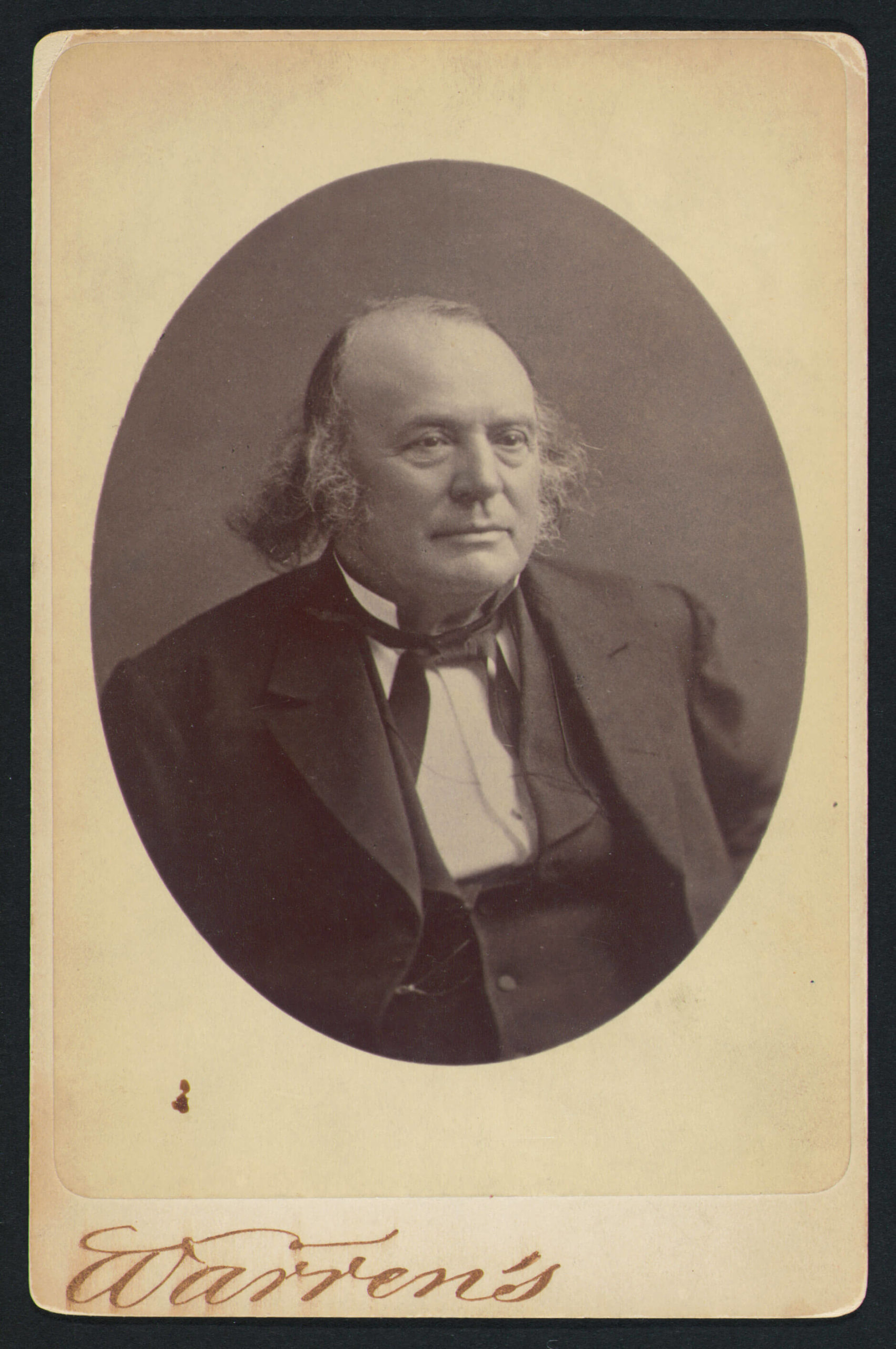

Agassiz, the Thyer Expedition and the Visual Construction of Blackness

As a pupil of renowned figures such as George Cuvier and Alexander Von Humboldt, and after studying in Switzerland, Germany and Paris, by the middle of the nineteenth century the Swiss Louis Agassiz had become one of the most prominent figures in Natural History, Zoology and Geology in Europe (Fig. 6). In 1847 he was appointed by Harvard University. There he founded the Cambridge Museum of Comparative Zoology and also became one of the most influential scientists in the United States, whose name continues to name streets, buildings, and research centers in this country. Known in some circles as the father of Glaciology, Louis Agassiz was the first supporter of the theory of glaciers. Systematic studies of glaciers as sequential phenomena are also attributed to him.

A follower of the proposals by his teacher George Cuvier, Agassiz advocated creationism (as opposed to Darwinian evolutionism) and polygenism, advocating, as far as possible, how the different “races” had distinct processes of creation (rather than a universal creation or monogenesis), and that blacks and whites had no common origin and therefore no genetic familiarity. This complex belief system considered humans to be divided into at least eight different species, whose origins were associated with eight different types of geographies. Each of these geographies could be distinguished by particular types of fauna and flora Funded by Boston banker Nathaniel Thayer, the official objectives of the scientific exploration were related to the collection of samples and images of fauna and flora, as well as the geological analysis of the territory. However, according to Gwyniera Isaac, Agassiz’s strongest motivation for starting the Thayer expedition in 1865 was to gather information that would oppose Darwin’s evolutionary theories. For the naturalist, Brazil was a territory with such a particular geography, fauna and flora that it would only prove the veracity of the differentiated geographical zones he defended. The differences in the races, and the degeneration derived from the mixing of races would also be susceptible to be proven, when gathering the information found in that territory (ISAAC, 1997).

The group that made up the expedition comprised a dozen people that included Agassiz as director of the expedition, students whom he guided, his son Alexander, and his wife Elizabeth, and a group of assistants that supported the commission. This group was also supported by the artist Jacques Burkhardt, French photographer August Stahl based in Brazil, and his assistant Walter Hunnewell (who learned photography in Rio de Janeiro). Most of Burkhardt’s drawings and watercolors are devoted to recording animal specimens, while Stahl and Hunnewell’s production for the expedition is entirely devoted to images of people, the former in Rio de Janeiro and the latter in Manaus and other territories of the Brazilian Amazon. This article is focused on the analysis of images made by Augusto Stahl, specifically the images that appear under the name of “Mina Bari”.

Analysis of the images of black men and women commissioned by Agassiz reveals that they were not part of a strictly scientific project, but were used to legitimize the previous agenda of a scientist with strong racial bias (ROGERS, 2006). Agassiz had stated his advocacy for the polygenetic creationist theory, and his trip to Brazil and the photographs taken there were intended to support his ideas rather than to prove them. In this sense, both the format and the staging of photographs, as well as the people selected to be in them, were part of a visual construction of blackness, totally different from that intended for white people. The enslaved people photographed were presented by Agassiz as a distinct, primitive species in comparison to white people, not susceptible to any mutation over time (as opposed to a possible evolution), coming from a geography with equally unique and immutable conditions.

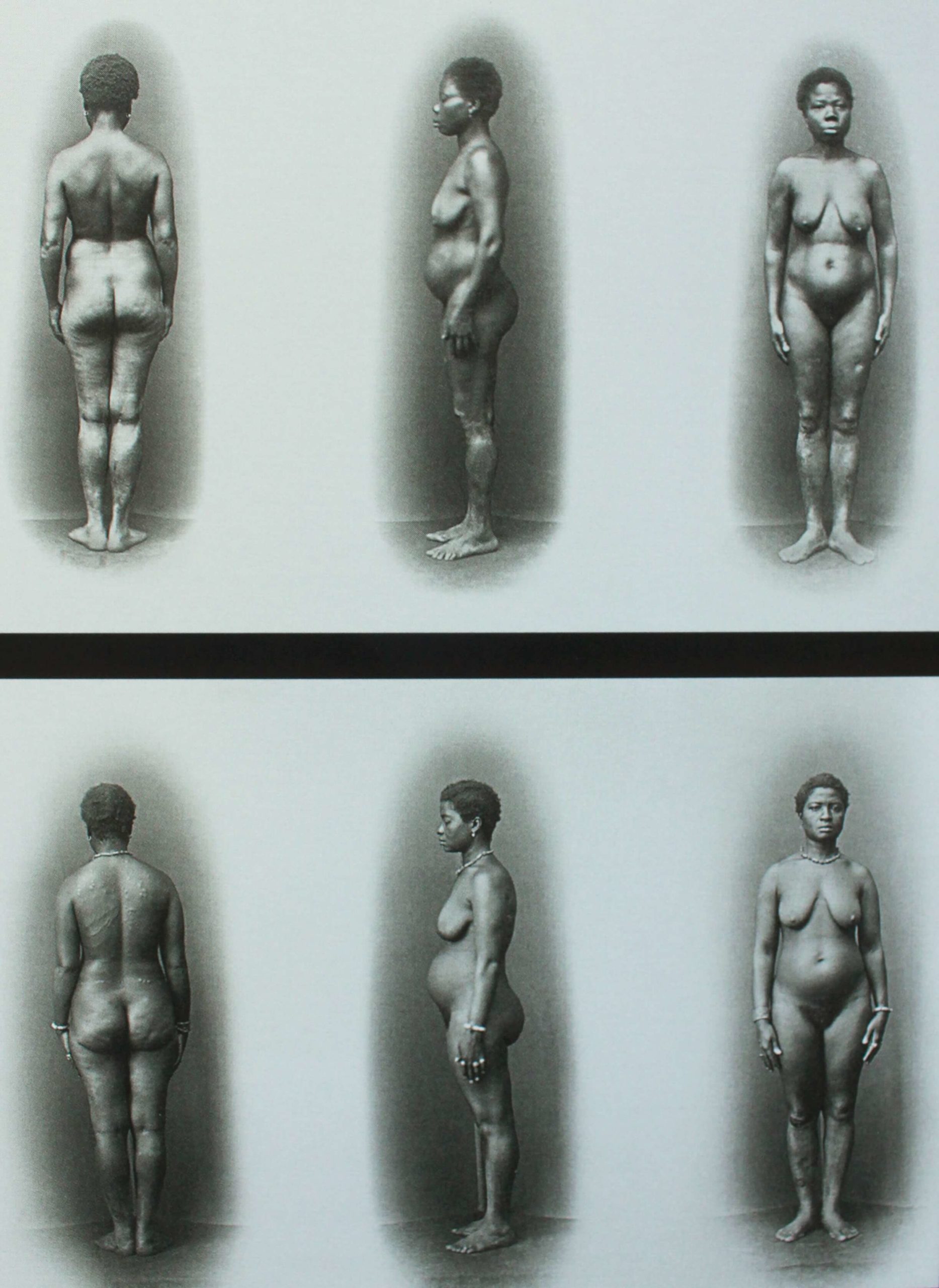

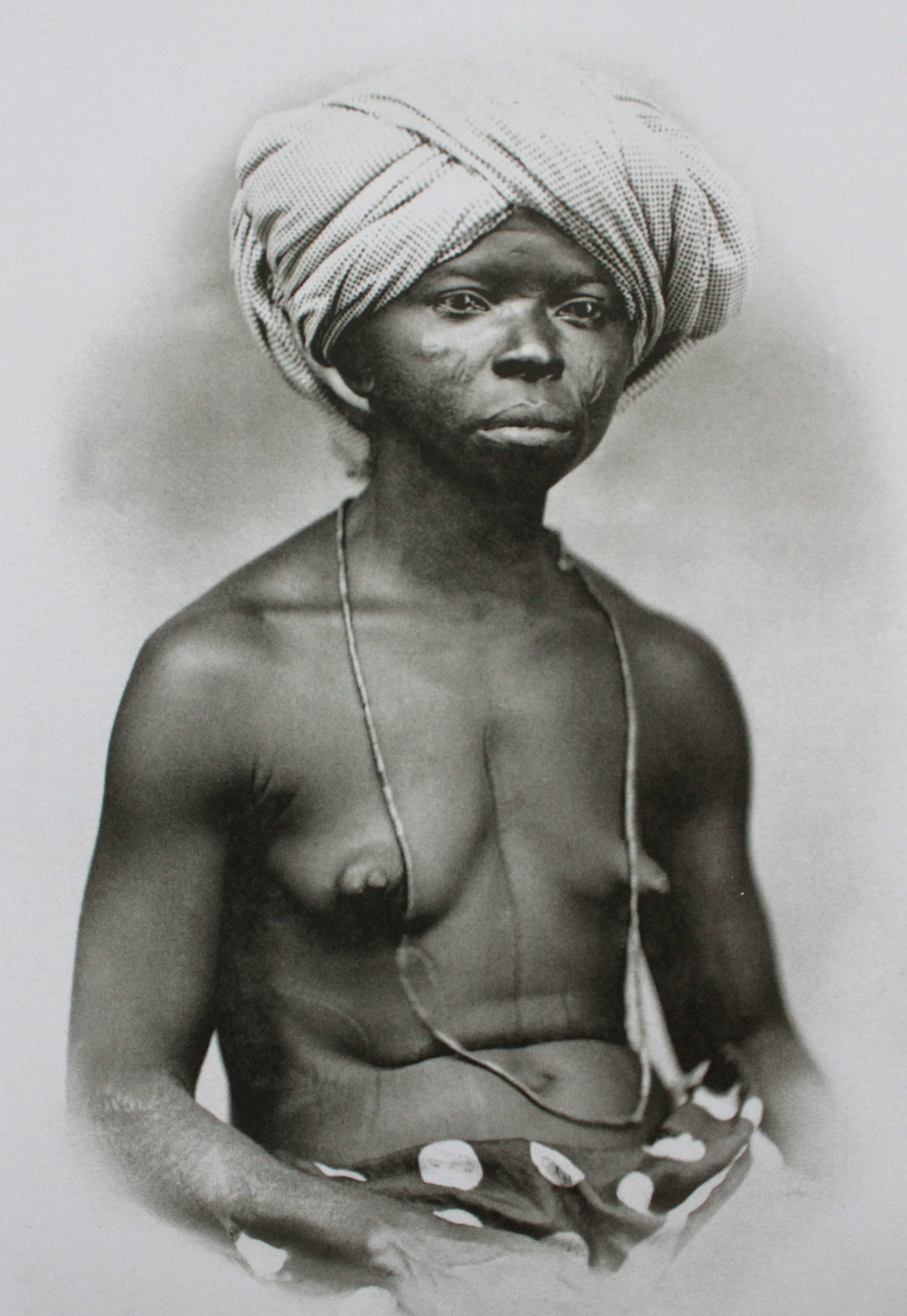

Images reveal the careful process of selection and staging employed by Agassiz. First, his interest in those with scarification is evident (see images 1,5,7,9 and 10). While Agassiz exposes it as an exotic sign bordering on the savage character that East African populations would have, the scarification seen in the images reveals a process of careful design and healing, which preserves geometric designs (vertical, horizontal, diagonal, or circular), revealing the belonging to a collective. (KEEFER, 2013, p. 537-553). The aforementioned images usually display scarification on the face. In some examples (Fig. 1), however, it also appears on the chest. In this case, the enslaved person to be portrayed has his clothes stripped to show the marks.

Another mise-en-scène presented as synonymous with “scientific” intentionality is to show people naked, in front, back and profile poses, emulating the principles of anthropometric photography. Here, nudity, rather than a symbol of scientific objectivity, emphasizes a pretended scarcity. This convention of the absence of clothes and ornaments as a symbol of such scarcity is a creation that, in the visual arts, may be traced back to the sixteenth-century painting handbook Iconology by the Italian Cesare Ripa. In this handbook, the Italian suggested the proper way to draw “virtues, vices, passions, arts, humors, elements and celestial bodies […]” (RIPA, 1593), and included the allegory of the four continents. These should be drafted following his instructions to ensure not only the correct representation, but also to preserve the hierarchy between them. In this context, among other attributes, the allegory of Africa of Africa should be represented as a dark-skinned woman, almost or totally naked because she misses abundant resources (RIPA, 1593, p. 53). These images, thus presented, offer a look at the body of black women as primitive, unclothed, unprotected beings. If Agassiz’s analysis of nudity were to follow a scientific method, he would consider similar images for white men and women as part of his study. This, of course, does not happen, and therefore, such images are not part of the images that accompany the expedition reports. Thanks to the testimonials of William James (compiled by Gwyniera Isaac), who was also part of the expeditionary group, we also know that such nudity, at least in the case of the indigenous populations in Manaus, was elaborated by Agassiz and his assistants. In one of his field diaries describing their activities while in Manaus, James describes how he meets Hunnewell, in the complex task of mastering photography, while people whom he knew firsthand that used to wear clothes and perfumes in the region, were persuaded to pose without clothes, and were labeled as indigenous. James states that, as would later be revealed, despite the insistence and elaboration to pass them off as pure indigenous, some of them were in fact mestizos (descendants of indigenous and white Portuguese) (ISAAC, 1997, p. 7).

Comparative analysis of some of the images housed in the Peabody museum reveal that, indeed, as described by James in Manaus, the black women photographed in Rio de Janeiro by Stahl were not nude. Rather, they had been undressed for the pictures. The description in the museum’s repository for (Fig. 1), refers to the woman photographed in clothes as “Mina Bari”, which is the same description that appears for the woman photographed later, this time naked. The same is repeated for the women in (Mina Nago) (Fig. 4 and 5). These representations of half-bodied women allude more to an “exotic” representation of black women, as types, as anonymous beings, than to a desire of portraying them. It is a type of image elaborated and commercialized also by other photographers in Brazil, such as José Christiano Junior and Alberto Henschel. These pictures were taken with the objective of being sold as souvenirs for those explorer travelers in the territory, or to be exported to other latitudes anxious to know the exotic tropical environment of the Americas.

As Beatríz Balanta puts it, the bodies of black women under Agassiz’s direction undergo a triple transformation in the photo studio: they are transformed into a scientific specimen, dressed in an artificial blackness, and further traded as merchandise (BALANTA RODRIGUEZ, 2012). This triple visual transformation made in these photographs contrasts with the images of the expeditionary group and Agassiz himself, displaying their best attire and making use of the resources that the photo studio could offer. Thanks to this construction of blackness, black women constitute “the ultimate other” (NELSON, 2010) in the social group, the direct opposition to those who would then be the dominant men, white, western, free, and enlightened: A species absolutely apart from the others by virtue of its impulsive gender, primitive race, naturalized need, and commodified body.

This agenda of construction of blackness set in motion by Agassiz in Brazil also took place in the South of the United States, in the crops in South Carolina, in 1850. At that time, the naturalist selected black people he considered of “scientific interest,” and commissioned his friend, colleague and tutor, Robert Gibbes, to bring them to the daguerreotype operator Josepth Zealy. Josepth Zealy produced the series of daguerreotypes that, like the images from the Thayer expedition, are today housed in the Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnology at Harvard University. Zealy’s images also show nude and semi-nude black men and women half-naked, and nude, front, profile, and back, just like the poses in Stahl’s pictures. The drama of their expressions, and the pain of seeing these images has been the subject of study and re-elaboration by artist Caree Mae Weems, who created the series From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried.

Legenda

Legenda Augusto Stahl. Mina Bari, c. 1865. Source: Rosana Paulino.

Legenda

Legenda Augusto Stahl. Mina Bari, c. 1865. Source: Rosana Paulino.

Legenda

Legenda Augusto Stahl. Mina Ondo, c. 1865. Source: Rosana Paulino.

Legenda

Legenda Augusto Stahl. Mina Nago, c. 1865. Source: Rosana Paulino.

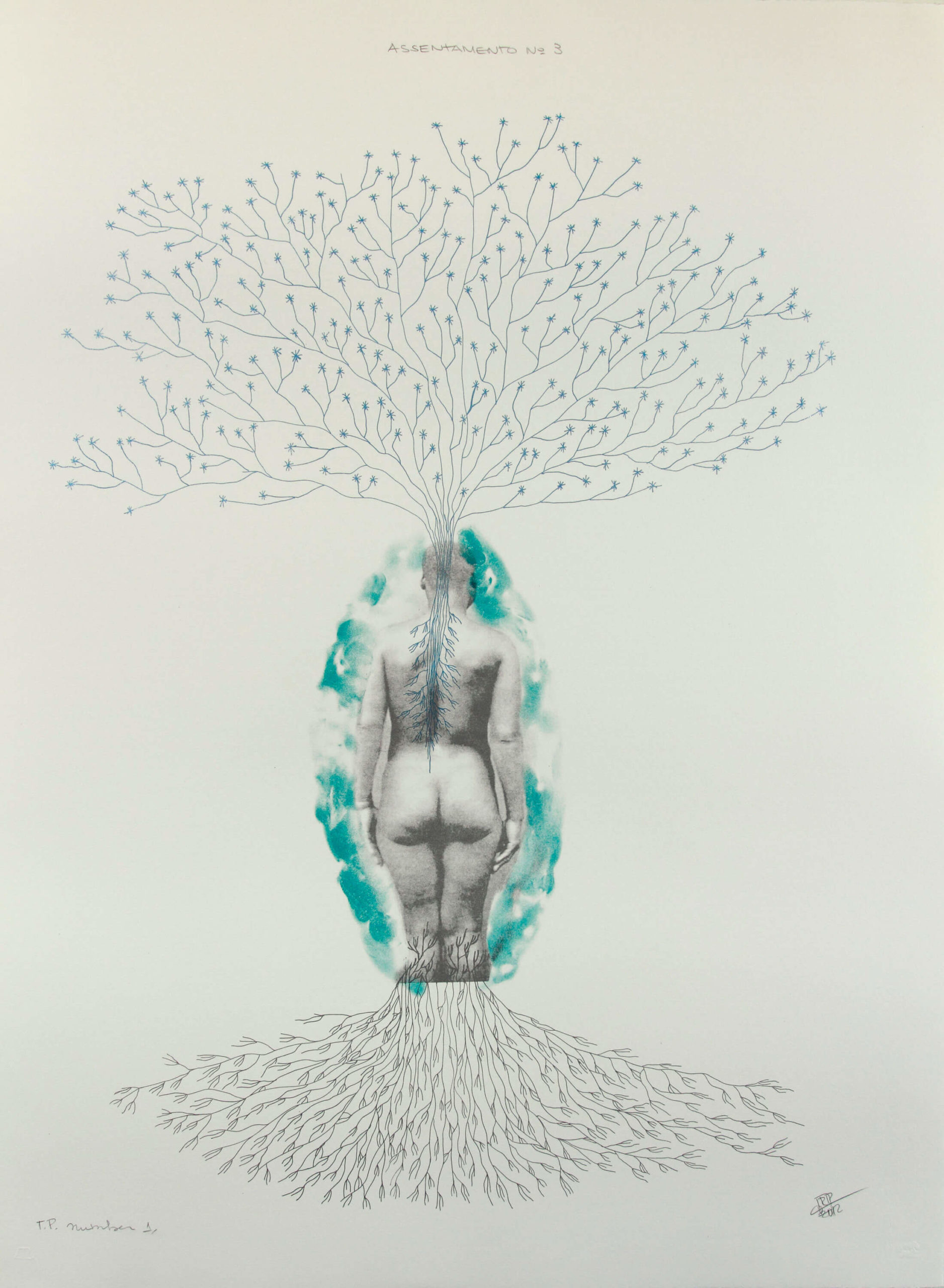

Rosana Paulino and Assentamentos

Like Carrie Mae Weems, Rosana Paulino, a contemporary Afro-Brazilian artist, is also impacted by the violence of the images created by Agassiz. The artist first saw the photos collected in George Ermakoff’s text O Negro na Fotografía Brasileira do Século XIX. In his descriptions in A Journey to Brazil, Agassiz describes how caravans of half-naked black men and women greet the expeditionary group with dancing and smiles, in each of the cities they visit. However, the images in the report are far from showing that joy and willingness to be photographed in that way. Their gloomy expression recalls that of the people in the images take by Zealy in South Carolina fifteen years earlier. There is no intention to exalt the humanity, the agency, the intelligence of those people exposed.

Assentamento is a critical intervention in the gaze, and in the collective memory. The artist seeks to evidence, protest the dehumanization of black women in these images, but she also intends to rescue and show their dignity, their culture and the great contribution of black women to the construction of the Brazilian society. The artist is showing how science has played a crucial role in masking the enormous contribution of black people to the Brazilian society, and how this masking still affects such recognition and the lives of contemporary Afro-Brazilian people. To do so, Paulino intervenes the same image found in the compilation in Ermakoff to “turn the key” and change that negative idea about black women, using “fire against fire” in this intervention. The artist states that “to cure all the evil caused by these images that violated the dignity of the black population, the same images should be used to change the key, bring dignity and show that these people contributed to the construction of a country” (PAULINO, 2021).

The raw material of Assentamento is the same images of Agassiz, specifically, the one named “Bari Mine” (Fig. 2), in which she is nude, from the front, in profile and from behind. Paulino takes this pseudo-scientific representation and reframes it in different ways at different scales. The first is a color lithograph on paper, re-signifying the image of “Mina Bari” in which she appears with her back turned (see Fig. 7). It is a re-presentation that starts from the denied individuality of the black woman, and becomes a collective recognition of her participation in the very foundations of the Brazilian society. Paulino emphasizes this collective rootedness in the same blue color that alludes to the sea that witnessed the voyage faced by the black population as a result of the Atlantic slave trade. The spirituality of black populations, initially exercised clandestinely, the music and culture of African matrix, throws light on the Brazilian territory to which they are brought. Paulino places the violent migration, the settlement, and the contribution to the national culture in the same blue-colored movement.

A second instance of resignification takes place again through another lithograph on paper that challenges and resignifies the role of motherhood for black women. On the one hand, it evidences the outrage of black bodies to which black women were subjected during enslavement, while on the other hand it recalls once again how this forced labor (among many others) made possible the reproduction of a labor force that eventually helped building towns and cities in the Brazilian territory. Once again, Paulino calls for recognition of the contributions to culture and the foundations of the Brazilian identity. In an interview, Paulino calmly recalls that if samba is the national dance (and its exaltation moves huge amounts of money through the Brazilian cultural industries), it is thanks to the presence and contributions of black people. Finally, and in Rosana’s words, the work scales. The year 2013 witnesses the assembly of Assentamento as an installation. That woman registered as Mina Bari, now life-size, faces the viewer. Her image digitally printed on canvases has been fragmented and imperfectly re-organized. Pieces of fabric have been joined to each other with thick black thread stitching, the edges of which hang from the seam/healing that have joined the parts of the woman together. A heart embroidered with red and black threads, bleeding, reminds us of the humanity, the violence, wounds, suffering they were subjected to during the slave trade. Violated women, forcibly settled in a new territory, reorganize themselves in an imperfect way and survive. On the sides of the image and on pallets, the artist places what from a distance seems to be firewood to be burned, but they are black arms so rigid that, in the end, they look like fossilized pieces of wood, tied together as if forming a pile ready to be lit. Simultaneously, these images of the sea are projected on digital screens, evoking the images of arms that once rose, trying to stand up and overcome the inevitable death in the sea.

Assentamento is a project that began in 2012, with the first color lithographs on paper. In them Paulino denounces the concealment of the image, and unveils what it seeks to hide: that black women were forced to stay in the American territory, and despite this they put down roots and contributed with their ideas, thoughts, and spirituality to turn Brazil into what it is today. Bathed by seas that witnessed the forced journey, the pain of enslavement, these women have used these experiences to literally give birth to the future of the country. The pregnancy of Assentamento 2 transforms the denaturalized profile photo into a memento of black men and women who were at the same time part of an intergenerational construction of the country by the same ethnic group.

Despite this strong protest against these “legally racist” constructions of black women from Natural History, it is not the artist’s intention to call herself an Activist or Artivist. Assentamento reflects on the racist visual constructions of black women legitimized by science in the nineteenth century, and how they affect the contemporary reality of black women. This reflection is intrinsically associated with Paulino’s construction of identity, being a black woman herself. Her work has a powerful voice, which for the artist represents an act of survival, not labels. As a black woman, she believes that her work should be done, as there is no other option to communicate her message in language, scale, and methods necessary, regardless of the names and labels in vogue (PAULINO, 2021). This way, Assentamento is a project in movement that changes scale and becomes an installation in 2013. For Paulino, it is necessary that the humanity of black women be scaled, resignified, even if this process implies a scar (Fig. 7 and 8).

Like artists such as Cuban Juan Roberto Diago, for Paulino that scar forms a keloid that resignifies the history of black populations forcibly brought to the American territory for exploitation. Diago represents the keloid through the thick welding mark on the metal. For Paulino, that keloid is represented through sewing, invoking in this way the crafts learned at home, as she does in other of her works. That mark, that keloid that evidences the history of violence, but also resignifies it, becomes, like the scarification of “Mina Bari”, an mark of black women’s identity. It should be shown denounced, but the pain inflicted on the bodies should be resignified to understand that, despite the multiple violence, we continue to exist in this territory, and we continue to contribute to the construction of Latin American nations. However, we should always draw attention to that contribution, show that keloid, sew that history into a thread that makes that imperfect reconstruction visible.

Rosana invites us to see those images with complaint, rage and eyes wide open. She also invites us to be participants in that narrative that unveils the tricks of scientific racism. It is impossible to know the specific conditions under which the image was taken, or the life of its model, of whom we only know she was identified by Agassiz or Stahl as “Mina Bari”. However, one can assume an active, denouncing observation of manifest pain, as Paulino suggests in her work (CARVALHO, 2008, p. 7). For example, denouncing, in an intersectional perspective, the alleged racial harmony of Brazil as a fallacy; denouncing also the clear racial and gender discrimination faced by Afro-Brazilian women; and denouncing the implications of such discrimination in their daily lives.

Legenda

Legenda Augusto Stahl. Mina Nago, c. 1865. Source: Rosana Paulino.

Legenda

Legenda Warren’s portrait. Louis Agassiz, 1860. HUP Louis Agassiz (13), olv work272187. Harvard University Archives.

The Chorographic Commission and the Image of Black Women

The Chorographic Commission was a scientific exploitation project of the then nascent country of Colombia, which took place between 1850 and 1859 headed by the Italian engineer Agustín Codazzi. The project was developed to learn about and recognize the physical and human geography, and map the territories of the newly independent country. These wars of independence showed that the former colony was already a fragmented territory, whose heterogeneity was clear in the way of facing the power vacuums, responding to the first and second stages of independence wars, and even with clear differences on which sides to support. Therefore, an enterprise aimed at getting to know the populations and territories was necessary if actions were to be taken in search of this unity.

Designed as a scientific exploration enterprise, the Commission incorporated the surveying methods and instruments of its predecessors, adjusting them according to the demands and scarcities of the territory. Codazzi had already learned to do it during his exploration of neighboring Venezuelan territory. This creativity was translated into the use of local informants and translators throughout the expedition, supplemented with histories of the region, whenever the conditions of the terrain made them completely inaccessible to his scrutiny.

Agustín Codazzi, director of the Commission, was heir to Alexander Von Humboldt’s theories and methods of measurement, observation and exploration. Von Humboldt had traveled around the Americas from 1799 to 1804. Von Humboldt was educated under the ideas of the Enlightenment by some of the most renowned German theorists, incorporating in his knowledge the early constructions around Linnaeus’ Taxonomy, and the European theories on races, climate and humors of Natural History, such as those promoted by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (NIETO OLARTE, 2010).

This is important to understand how, under the banner of scientific objectivity, the images, maps and information collected within the framework of the Commission constituted the basis on which the first territorial policies of the country were built, and significantly affected the construction of a national imaginary. In her text, Mapping the Country of Regions, Nancy Appelbaum (2016) would argue that, despite the ideal of unity that preceded the Commission planning, results show a country with racial and territorial diversity, whose documentation reflected the racial preconceptions of those who took part in the enterprise. Based on this information, partially affected by racial prejudice, a series of laws were established favoring territories with a majority of white and white-mestizo populations in the highlands of the central Andean region, to the detriment of territories with a majority indigenous and Afro-descendant population in the periphery.

The root of these constructions has to do with an approach based on Natural History that assigned certain behaviors, moods and values to each race and gender. “Men of Science” would take into account the temperature, humidity and atmospheric pressure of the territories as factors affecting the moods of the different races in the then Viceroyalty of New Granada (NIETO ORLARTE, 2009). In other words, although the Chorographic Commission happened when the country was independent from the Spanish power, sciences were still influenced both by the supremacy of the European knowledge, and by those elite white men who, educated under a colonial regime, appropriated this knowledge of race hierarchization.

These ideas, however, are not homogeneous in the Commission. In fact, Nancy Appelbaum finds discrepancies between the watercolors produced and the maps and written reports presented, especially in the region of Antioquia. While the images produced by Henry Price show a diversity of population that includes black, indigenous and brown men and women, the report refers to a concentration of white and white-mestizo population, whose race (and the associated values of good workers) would guarantee the development of such an area. This is, in fact, a construct that survives to this day. The region of Antioquia and the city of Medellín are represented in the national imagination as regions with an exclusive or majority white population. Hence the importance of Henry Price’s Retrato de una Negra.

Legenda

Legenda Rosana Paulino. Assentamento, 2012, color lithograph on paper. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo – MAC USP.

Legenda

Legenda Rosana Paulino. Assentamento, 2013, digital printing on fabric, embroidery, linoleum, stitching. Source: Rosana Paulino.

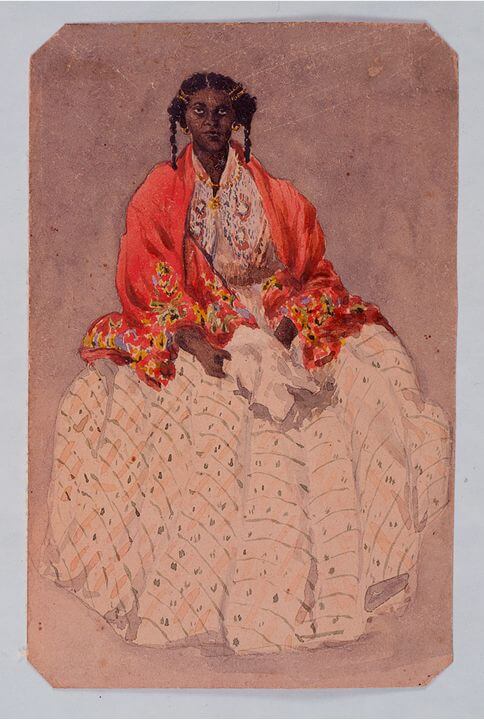

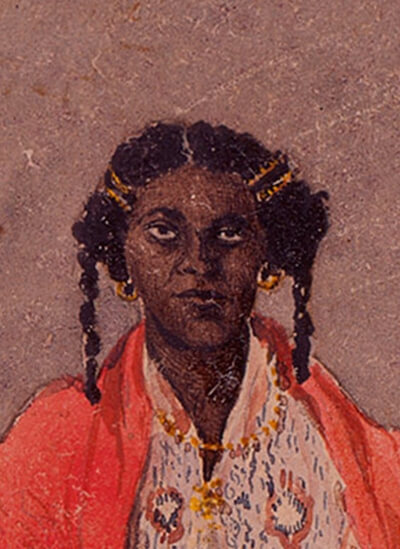

Henry Price, Retrato de una Negra (1852)

There are nine images depicting black women among the more than two hundred images that make up the Chorographic Commission. Among these nine, Henry Price’s images of black women seem to show them in a different light, more central, more key to the scene, and more defiant in looking at the viewer. However, Retrato de una Negra definitely makes a difference with respect to the visual language in which the Commission depicts black women and endows them with a status that can hardly be matched in another of the Commission’s images.

The portrait format chosen for the image already speaks to us of a need for individuality of the person being depicted. The woman is sitting and richly attired in a loose, long skirt, possibly made of cotton, that covers her feet, and whose volume occupies almost half of the composition’s front plane. She is wearing a blouse with engraved images and an orange cloak with embroidered flowers at the ends. She wears jewelry in her hair, a necklace and golden hoop earrings. She holds in her hands a white handkerchief, open and crumpled. Her eyes look directly at the viewer.

Could Price have followed the approaches of the nineteenth-century human type painting, and could portrait have been produced as an exotic image of a black woman in Antioquia? Undoubtedly Price’s representation shares some elements of the postcards produced by the photographer Christiano Junior in the second half of the nineteenth century in Brazil. These postcards were produced with the aim of being exported as souvenirs, visual witnesses of the racial exoticism of this country. Price’s work also shares elements with some of the images produced by Pancho Fierro in Peru, in the middle of the same century. The anonymity of the model, who is named as a specimen of her race (a black woman), would also account for this representation that denies individuality and exoticizes collectivity. It is also true that the images of black women produced by Price within the framework of the Commission differ from those produced by his exploration colleagues, especially those of Manuel María Paz. It does not necessarily mean that Price’s image seeks to elevate the black women he portrays or that it seeks to subvert the prevailing racial hierarchical order of the moment. However, for artist Liliana Angulo it is particularly intriguing that Henry Price painted Retrato de una Negra in 1852, which is recognized and celebrated in Colombian history as the year in which the enslavement of people was definitively prohibited in the country. This fact awakens her interest, and leads her to investigate more about this work.

Legenda

Legenda Henry Price. Portrait of a Black Woman (Province of Medellin), 1852.

Legenda

Legenda Liliana Angulo. Portrait of Lucy Rengifo. Project “Black Presence”, 2007.

Legenda

Legenda Liliana Angulo. Portrait of Lucy Rengifo, Project “Black Presence”, 2007.

Legenda

Legenda Liliana Angulo. Portrait of Lucy Rengifo, Project “Black Presence”. 2007.

Legenda

Legenda Liliana Angulo. Portrait of Lucy Rengifo, Project “Black Presence”, 2007.

Legenda

Legenda Liliana Angulo. Portrait of Lucy Rengifo, Project “Black Presence”, 2007.

Legenda

Legenda Liliana Angulo. Portrait of Lucy Rengifo, Project “Black Presence”, 2007.

Liliana Angulo and the Retrato de Lucy Rengifo

The past has always been present in Liliana Angulo’s work. Her first project, “Un Negro es un negro”, took more than five years, and incorporated several productions. In Porteadores her concern with photographic images from the second half of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth century is evident, depicting African people about to be sent to other territories, carrying objects that would be traded, just like their bodies. In the series Negra Menta and Negros Utópicos, Angulo exaggerates the features of her face in an intentional black face, and dresses with the fabrics used to make tablecloths and kitchen curtains. This way, she shows the paradox of restricting the roles of black people to domestic occupation, while assuming their total and absolute happiness in such entrapment. Both the images that deny the agency of African and Afro-descendant people and the contemporary stereotypical constructions are part of “Un Negro es un Negro”, whose objective was to evidence the dehumanization and theft of agency of black people in these images, and to think over current implications of these images in the construction of what an Afro-descendant person is, and their place and role in contemporary Colombian society.

After carrying out this project for five years, the artist seeks other horizons that vindicate the agency of black people. That is how she gets to at Henry Price’s Retrato de una Negra, and plans to make Retrato de Lucy Rengifo (see images 10-16). This is one of the first works of her project “Presencia Negra”, a long-term project in which Angulo seeks to show more of the agency of African descent people, their representation and their contribution to visual and scientific projects, and to the construction of the country. Her current work, Un caso de Reparación Histórica, explores the contributions of free and enslaved black people to the Botanical Expedition project, led by José Celestino Mutis from 1783 to 1816 in New Granada. In this sense, we see that for Angulo, as well as for Rosana Paulino, there is a strong need to influence the historical visual memory through her artistic intervention. Pointing out and highlighting the contribution of black communities to the construction of the countries in which they live becomes a fundamental reason for the production of their works.

In the case of Retrato de Lucy Rengifo, it is a recreation that the artist considers necessary based on her own reality. Liliana Angulo met Lucy Rengifo at the Universidad de los Andes. Rengifo was pursuing her degree in Political Studies. Angulo was taking some courses in Anthropology at the same University in the city of Bogota. Rengifo and Angulo were the only black women in the courses they shared, and this fact aroused the artist’s interest. When they met, Liliana Angulo discovers that Rengifo was born and raised in the city of Medellín, the same city where Price’s portrait was painted (ANGULO, 2021). Race and territorial location are of significant interest, both in Price’s work and in Rengifo’s particular story. In the Colombian national imaginary, Medellín is a city that is understood to be inhabited mostly by white and mestizo people and, therefore, is not collectively thought of as a city inhabited by Afro-Colombians, even though this is the case.

More than a reaction, Liliana Angulo describes her work as a “re-enactment” of Price’s work. In an exercise similar to that proposed by Saidija Hartman (2008, p. 1-14), listening and above all challenging the archive, Angulo wonders who this woman might be. Beyond assuming that she is an enslaved person, adorned for the merit of some patron, from the portrait format chosen by the watercolorist and the defiant way in which she has been painted, Angulo wonders if she is some prominent figure in the Antioquian society. Like Hartman, the artist raises questions, which the available archive does not resolve: “could it be that she was already a free person? Had she bought her freedom? Were those jewels made of gold? Was she herself the owner of enslaved people? (as texts of the period have shown) (ANGULO, 2021). Angulo knows that it is difficult to know more about the woman painted by Price, whose eyes look straight at the viewer, free of the submissiveness that is imprinted in the gazes of the African people in the nineteenth-century photographs of porters on the African coasts.

Regarding the fact that it is a portrait, Angulo wonders “Who would be this black woman to deserve such treatment at that time?” Rather than ignorance or innocence with respect to the canons of representation of the mid-nineteenth century, Angulo invites us to reject the lack of agency of enslaved people in the images presented to us. Instead, through a visual recreation (a critical visual fabulation, to use Saidija Hartman’s words) she allows us to critically speculate other realities, other possible worlds for those women whose lives we do not know. The portrait of Lucy Rengifo, thus, with her own name, allows us to raise these speculations in a visual way.

Lucy Rengifo is herself in her twenty-first century: A black woman, born in Medellín, a political scientist and advisor to different entities, and a regular inhabitant of mostly white spaces. The actual Lucy Rengifo will not give us answers regarding the black woman painted by Price. However, the recreation proposed by Liliana Angulo, who rescues Price’s painting from anonymity, opens the door to multiple questions that, in Angulo’s reasoning, invite us to think about the agency of black people, despite the adverse circumstances in which they lived. It does not mean disguising the reality of their contexts, but it does mean resisting the imposition of images validated by an alleged scientific objectivity that gives out a voiceless blackness. It invites us not to give in to the pretensions of such constructions, and to try to critically fable their positions in societies and the strategies to get through them. In this way, following the guidelines proposed by Angulo, the portrait of Lucy Rengifo poses a reflection in three ways: first, it expands and complicates the spectrum of representations of Afro-descent considered for the nineteenth century; second, it poses a past-present reflection between race, gender and region; and finally, it explores the constructions of the contemporary black women’s identity.

As part of Retrato de Lucy Rengifo, the artist developed activities with women leaders in the city of Medellin, Antioquia. Thanks to an invitation from the Museo de Antioquia, Angulo has been holding conversations with female leaders, and asking them about their impressions of Price’s portrait. In addition to the discussions that arose in these meetings, workshops were held incorporating family images, and posters were produce intervening in the spaces where these women live in the city of Medellín. These posters incorporate the phrases that emerge in the discussions, taking to the streets of the city questions about race and ethnicity, something that is rarely discussed in a city that denies the presence of Afro-Colombian citizens.

Legenda

Legenda Liliana Angulo. Portrait of Lucy Rengifo, Project “Black Presence”, 2007.

Legenda

Legenda Henry Price. Portrait of a black woman (Province of Medellin), 1852.

By way of conclusion

Since the nineteenth century we have witnessed an amalgamation of science, geographic exploration, human differentiation, and visual culture. Scientific knowledge is co-opted by enlightened elites, and used to legitimize racialized visual constructions. It is not fortuitous that, when tracing the influences of the leaders of the expeditions studied, Agustin Codazzi and Louis Agassiz, both lead us to the approaches of Alexander Von Humboldt, George Cuvier and Karl Linnaeus. White and European men modeling nature in a hierarchical way. In this context black women are constructed as primitive, inferior, impulsive subjects, perfect opposites of those western white men who also commission the images that represent them. Once established in the visual language, these images affect the realities of contemporary black women. Then, what could be done to respond to them?

Rosana Paulino invites us to re-signify those very images that dehumanize black women. Her response involves an intervention that denounces the violence of these images, points out the sins of their creators, and the consequences in the daily lives of women like her. But this protest also invites us to remember the invaluable contribution that black women have made to the construction of Latin American nations, and Brazil in particular. These images not only dehumanize, but also underestimate the agency of black populations to resist continuous violence, and their participation in the construction of the country.

For her part, Liliana Angulo recreates a work that she considers deserves special attention. Through Retrato de Lucy Rengifo the artist recreates and asks questions to Henry Price’s watercolor Retrato de una Negra (1852). Similar to Saidija Hartman’s critical fabulation, Angulo proposes to question images with a different intentionality, so as to consider other realities that take into account the agency of black women. It is true that the exercise of denouncing must be done, but given the wear and tear that it generates it is valid to critically scrutinize the archive, in search of those actions that reveal the will of black populations, despite the oppressions to which they were subjected.

Both artists intervene in different ways the images of the past that generate concern in them. While Paulino emphasizes the denunciation of violence, and the exaltation of participation in the construction of society, Angulo proposes an insistent search for the traces that reveal the agency of black populations. Both artists coincide in the need to influence the collective visual memory, remembering or excavating the evidence of active participation of black communities in the major projects that defined the nations’ foundations. Such reflections are inseparable from their realities as black women inhabiting geographies that deny them, and attending spaces in which they are also minorities.

References

ANGULO, Lilian. Entrevista. Out. 2021.

APPELBAUM, Nancy P. Mapping the Country of Regions: The Chorographic Commission of Nineteenth-century Colombia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

BALANTA RODRÍGUEZ, Beatriz Eugenia. Especímenes Antropométricos y Curiosidades Pintorescas: la Orquestación Fotográfica del Cuerpo “Negro” (Brasil, circa 1865). Revista Ciencias de la Salud, vol. 10, n. 2, 2012, p. 223–242.

BINDMAN, David. Ape to Apollo: Aesthetics and the Idea of Race in the 18th Century. London: Reaktion Books, 2002.

CASTRO GÓMEZ, Santiago. La Hybris del Punto Cero: Ciencia, Raza e Ilustración en la Nueva Granada (1750-1816). Segunda Edición. Bogotá: Editorial Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Instituto de Estudios Sociales y Culturales Pensar, 2010.

CHILDS, Libby/ CHILDS, Adrienne L./LIBBY, Susan Houghton. Blacks and Blackness in European Art of the Long Nineteenth Century. Farnham Surrey, England; Burlington: Ashgate, 2014.

DIONÍSIO, Gustavo/ SUGAWARA, Gisele. Rosana Paulino: Arte, Crítica, Subjetividade. Revista Gênero, vol. 19, n. 1, 2018, p. 148.

HALL, Stuart (ed). Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: Sage, 1997)

HARTMAN, Saidiya. Venus in Two Acts. Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism, n 26, 2008, p. 1-14.

ISAAC, Gwyniera. Louis Agassiz’s Photographs in Brazil: Separate Creations. History of Photography, vol, 21, n, 1, p.3–11, 1997

KEEFER, Katrina H.B. Scarification and Identity in the Liberated Africans Department Register, 1814-1815.Canadian Journal of African Studies, vol, 47, n, 3, p. 537–553, 2013.

NELSON, Charmaine. Representing the Black Female Subject in Western Art. Routledge Studies on African and Black Diaspora. New York, NY: Routledge, 2010.

NIETO OLARTE, Mauricio. Americanismo y Eurocentrismos: Alexander Von Humboldt y su Paso por el Nuevo Reino De Granada. 1.st ed. (Colección Séneca). Bogotá, D.C., Colombia: Universidad De Los Andes, Vicerrectoría De Investigaciones, Ediciones Uniandes, 2010.

NIETO OLARTE, Mauricio. Orden Natural y Orden Social: Ciencia y Política en el Semanario del Nuevo Reyno de Granada. Bogotá D.C.: Universidad de los Andes, Facultad De Ciencias Sociales-CESO, Departamento de Historia, 2009.

NIETO OLARTE, Mauricio. Remedios Para el Imperio: Historia Natural y la Apropiación del Nuevo Mundo. Bogotá, Colombia: Instituto Colombiano de Antropología y Historia, 2000.

PAULINO, Rosana. Entrevista. Out. 2021

RIPA, Cesare. Iconologia, Overo, Descrittione Dell’imagini Vniversali Cavate dall’antichita et da Altri Lvoghi. Roma: Gli heredi di Gio. Gigliotti, 1593.

ROGERS, Molly. The Slave Daguerreotypes of the Peabody Museum: Scientific Meaning and Utility. History of Photography, vol 30, n, 1, p. : 39–54, 2006.

SILVA, Renán. Los Ilustrados de Nueva Granada, 1760-1808: Genealogía de una Comunidad de Interpretación. 1.st ed. Medellín: Banco De La República: Fondo Editorial Universidad EAFIT, 2002.

WALLIS, Brian. Black Bodies, White Science: Louis Agassiz’s Slave Daguerreotypes, American Art, n, 2, 1995, p. 38-61.