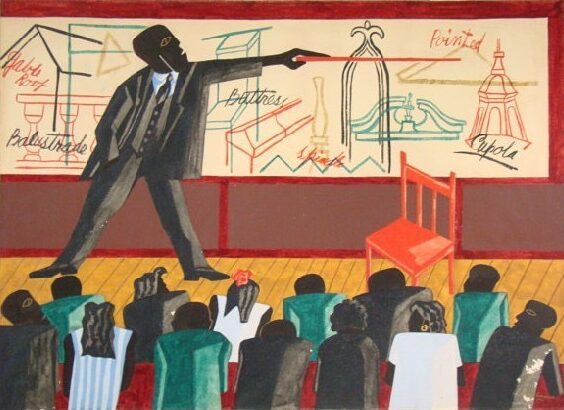

Class, Lecture or Lecture on Architecture. These are the titles ascribed to Jacob Lawrence’s painting in the MAC USP collection. Produced in 1946, the work features typical elements of the artist’s vocabulary, such as sparse use of colors and geometric treatment of shapes. It is organized according to horizontal lines that mark the section reserved for the students, the floor where the professor is standing, the line created by the master’s raised arm, elongated by the baton, and the plane of the board. On that light surface we see colorful drawings illustrating architectural elements described by captions, such as “balustrade” and “cupola.” The professor, standing with his legs apart, forming a triangle, and with outstretched arm, makes for a sturdy and energetic figure. He is wearing a jacket, tie, vest and a shirt between white and blue, echoing shades present in the students’ clothing. His hand is comfortably place in his pocket as he is observed by the class. The students, men and women, are viewed from the back, but those seated on the far left and right reveal a synthetic countenance seen in profile, in the manner in which the teacher’s features are depicted, marked by the dark tone rather than facial traits. There is no table, but a chair offers the most vibrant color in the picture, whose bareness may evoke the respectable nature of the teaching profession or the future possibilities open to students who come to inherit this trade.

The painting dates from 1946; therefore, we are in the USA of the segregation system known as “Jim Crow laws,” in force between 1881 and 1964 and widespread in most US states, more vigorously in those located in the South. A more comprehension view of this system is offered by recognizing its different dimensions. Economic oppression imposed the worst jobs on blacks, reserving the best for whites, sometimes exclusively. The denial of voting rights for blacks was a key element of political oppression. White judges and juries ratified trials in which black witnesses could not speak out against whites, in a dynamic of legal oppression that made it difficult for African Americans to win cases in court. Social oppression was based on segregation that separated or banned black persons in hospitals, buses, restaurants, hotels, movie theaters, prisons, cemeteries, and of course, schools and universities. Personal oppression was sustained by attitudes and behaviors adopted by white individuals, who were aggressive or rude, with practically assured impunity in situations of violence. There were even bans on public displays of affection between blacks, considered offensive to whites.

The main premises underpinning this denial of the rights of people of African descent stemmed from distorted views of African Americans as lacking in character, intelligence and qualities. In the perverse dynamics governing that society, segregation ultimately benefited everyone, including blacks, as they could be saved and motivated to progress under the guidance of white society. We know, however, that African Americans resisted and fought the arbitrariness of this system in many different ways. A case in point is the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, NAACP, an organization founded 1909 whose main cause in the mid-twentieth century was fighting against segregation in education.

The political philosophy based on the false principle of “separate but equal,” which preached that in segregation whites and blacks would be separate but enjoy equal opportunities, also applied to education. The truth is that the best equipped schools and universities were dedicated exclusively to white students. The arguments against integration of black and white students were fueled by fear of increased interracial marriages; fear of reduced cheap labor for industry and agriculture; and fear of greater difficulty to control black social groups if they were better educated. If until 1863, when slavery was abolished in the US, the idea was that education spoiled slaves, the aim now was to offer an education to keep blacks “in their place.” Blacks also lived in greater numbers in rural areas, where the quality of education was lower and children were forced to drop out of school to contribute to the family income, leading to a context in which different factors conspired against the acquisition of greater knowledge by black communities.

In the same year Jacob Lawrence produced his painting, Heman Sweatt applied for admission to law school at the University of Texas, which was then attended exclusively by whites. According to a law at the time, provided there was a black college on campus, no black student would need to be admitted to study in the company of whites. Therefore, the state funded the creation of a black law school in the university, but of inferior quality. The NAACP and the then black attorney Thurgood Marshall, who would go on to become a Supreme Court justice, filed a lawsuit demanding Sweatt’s admission to the pre-existing institution. His victory highlighted the frequent provision of separate and unequal conditions. Black universities had existed since the 1860s, fundamental educational institutions attended by, to give more recent examples, the US Vice President Kamala Harris (Howard University), Oprah Winfrey (Tennessee State University) and Martin Luther King Jr. (Morehouse College). The existence of these institutions may suggest a realistic view of Jacob Lawrence’s image, but I believe that there is another underlying perspective, more aspirational and idealized.

The first post-World War II riot also dates from 1946. Cases of assault, beatings—one leaving a man permanently blind, the other seriously injuring a woman—brutal murders and an attempted lynching led to a popular mobilization of blacks in the city of Columbia, Tennessee. The occurrences added to the dissatisfaction of war veterans who had fought for freedom in Europe, according to the government’s discourse, and returned to the US to find themselves in the position of second-class citizens, willing to fight for freedom in their home country. The conflicts involved breaking into homes of black families, looting and considerable destruction over the course of two days, resulting in the arrest of dozens of blacks, who would be represented by NAACP lawyers, but no whites detained. This event gives us an idea of the mood at the time, its tensions and levels of violence, but also of the ways which African Americans reacted and fought back, whether individually or as communities and organizations.

Legenda

Legenda Jacob Lawrence. The Class, 1946. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo. ©Lawrence, Jacob, AUTVIS, Brazil, 2022

Lawrence was born in Atlantic City, New Jersey, but his artistic sensibility was forged in a unique microcosm: Harlem. A black New York enclave and major reference point of American culture in the 1920s and 1930s, Harlem was Lawrence’s school of modernism. He arrived in New York, the final destination of his family’s migration from the US South, at the age of 13, in 1930. Lawrence grew up surrounded by jazz, the effervescence of the streets and the legacy of the Harlem Renaissance, which paved the way for different forms of artistic creation: painting, sculpture, literature, drama and music, through jazz. This renaissance symbolically expressed the idea of the New Negro.

According to the philosopher Alain Locke, who published a book titled The New Negro in 1925, the New Negro is aware of inequalities, more alert to changes in the modern world, more self-confident and assertive than the “Old Negro.” A placard carried during a march in Harlem in those years bears the words: “The New Negro has no fear” (Fig. 2). He is also prouder of his origins, ready to express himself freely and to challenge the stereotypes and aesthetic standards of white culture (Fig. 3). The writer Langston Hughes viewed the possibility of dark-skinned individuals expressing themselves as a force at the time. Experimentation, focused on addressing themes related to the African American experience, was encouraged and celebrated, giving prominence to artists, leaders and intellectuals such as W.E.B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, Josephine Baker, Zora Neale Hurston, Aaron Douglas, Augusta Savage, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday. The “New Negro” was a project that distanced African American individuals from memories and images of slavery. It was a utopian project based on language that aimed at the reinvention of a race through largely imaginative action, and it is in this environment that Lawrence develops as an artist.

Legenda

Legenda UNIA Parade, organized in Harlem, 1920. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1920. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, New York Public Library. Source: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/ae302a0e-9e0d-dd4c-e040-e00a18067bd1.

Legenda

Legenda James Van Der Zee. A member of Garvey’s African legion with his family, 1924. MoMA.

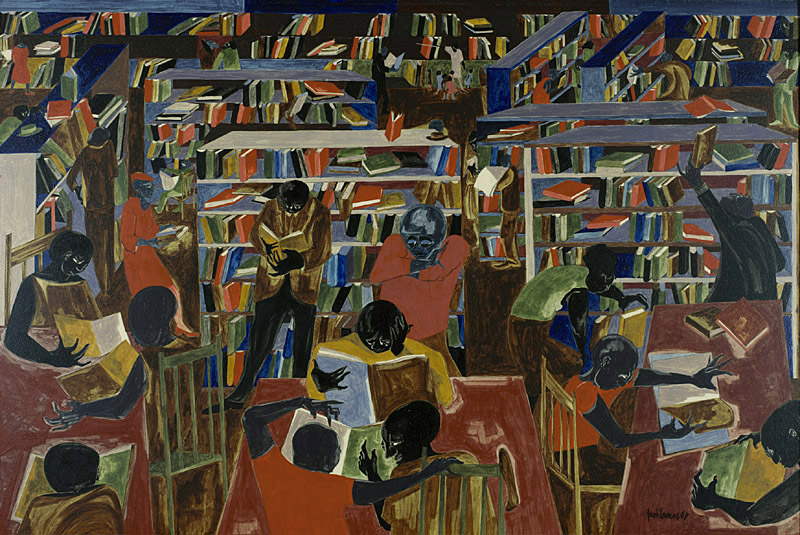

The expectation of the emergence of new identities and greater respectability within American society led to a longing for education, or even self-education. In Jacob Lawrence’s work, other paintings besides Lecture on Architecture depict school and library as important spaces. He was a frequent user of the public library on 135th Street, to which he pays a tribute in several paintings, and which became the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the first significant collection of African American literature, history and culture, opened in 1925. Examples of paintings that address the subject matter he addressed over the years are: The Libraries Are Appreciated, 1943 (Philadelphia Museum of Art), The Library, 1960 (Smithsonian American Art Museum), and The Library, 1967 (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts) (Fig. 4).

Legenda

Legenda Jacob Lawrence. The Library, 1967. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. ©Lawrence, Jacob, AUTVIS, Brazil, 2022.

Another work can be added to enrich this set. The painting In the North the Negro Had Better Educational Facilities (Fig. 5) is part of his fundamental Migration series. Between 1940 and 1941, Lawrence researched in texts and in conversations with family members and acquaintances the history of the American Great Migration to compose a series of 60 paintings that are iconic today. This narrative series addresses the exodus of more than six million African Americans from rural southern states such as Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana to northern cities like Chicago, Detroit and New York in search of job opportunities during and after World War I. As we have seen, they were fleeing from the Jim Crow system, the poor living conditions and the constant threat of lynching, which was rarer in the north of the country, where black people found relative security as long as they stuck to their generally impoverished neighborhoods, despite still facing racism per se.

Legenda

Legenda Jacob Lawrence. In the North the Negro had Better Educational Facilities, 1940-1941. MoMA. ©Lawrence, Jacob, AUTVIS, Brazil, 2022.

The titles of the paintings, to some extent didactic, constituted a historical discourse emphasizing the black American experience. In In the North the Negro Had Better Educational Facilities, Lawrence draws on geometric construction and synthetic vocabulary to show three girls viewed from the back writing numbers on a blackboard. The numbers 2, 3, 4 create an ascending line that follows the height of the characters, creating a suggestive image of the possibilities of development and advancement through education. The work in the MAC USP collection was made five or six years later than this one, but revives the image of the board and the presence of students, who in this case are in elementary rather than higher education. Training in working-class crafts is also addressed by Lawrence, as in the painting A Class in Shoemaking from 1947, belonging to Carnegie Mellon University’s Hunt Library.

In 1946 he exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris and Tate Gallery in London, having been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship at the time. By then his career as the greatest African American artist of 20th century was already consolidated, considering the presence of his works in museums and collections outside the black community. That year, the same in which the work in the MAC USP collection was painted, Jacob Lawrence was invited to lecture in a summer program at Black Mountain College, a progressive university focused on the arts, located in Asheville, North Carolina, accompanied by his wife, the also artist Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence. Concerned about the violence of racism in the South, the couple never once left campus and got around by car to avoid being subjected to the segregated seats of public transport. The invitation was made by Josef Albers, a refugee artist from Nazi Germany linked to the Bauhaus and a professor at the university. This experience was memorable, stirring a long-lasting interest in teaching that led him to work in different higher education institutions such as the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, in Maine, the New School for Social Research, in New York, and the University of Washington, in Seattle. He claimed that teaching prompted him to explore and forced him to crystallize his own thinking, to formalize his theories so as to communicate them to his students. Thus emerged a continuous cross-fertilization between studio and classroom.

The painting at MAC USP can also been seen to dialog with another of his works in which the subject matter is likewise architecture, but as a craft rather than a discipline. It is The Architect (1959) (Fig. 6), belonging to the collection of the Studio Museum of Harlem, an institution to which he contributed in several ways. The character spreads out a blueprint as he contemplates the same urban landscape we visualize. Construction beams create an orthogonal pattern in the outdoor environment, ready to give structure and shape to what has been conceived by the architect. This 1946 painting creates a representation of the city that never ceases to change, energized by the capacities of the human mind and human achievement, while suggesting the possibility of black individuals being part of the adventure of this creative force, with the power to design the present and future of metropolises.

Legenda

Legenda Jacob Lawrence. The Architect, 1959. The Studio Museum in Harlem ©Lawrence, Jacob, AUTVIS, Brazil, 2022

The MAC USP painting is part of a museum collection composed of 14 works specifically purchased by the millionaire Nelson Rockefeller for a donation, a symbol of the friendship between Brazil and the USA in the immediate post-war period. Besides Jacob Lawrence, it included works by artists such as Morris Graves, Alexander Calder and Marc Chagall. Some of them, therefore, were European, but active in the US, representing different art trends, all of them opposed to the aesthetic defended by the fascist regime. The generous gift of the millionaire and prominent art collector was made to help set up the first Museum of Modern Art in Brazil, which would be inaugurated in 1948 after this so-called “shot in the arm,” as the US government described the donation. The set of paintings totaled just over US$ 7,000, which today would be almost US$ 100,000, or over half a million reais.

On arriving in Brazil in 1946, Rockefeller stated his wish to contribute to the well-being of the country and defend the cause of contemporary creative genius. He had already founded an association to contribute to health, housing, education and the economy in Latin America, the American International Association (AIA), after being coordinator for Inter-American Affairs in the government of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, whose goal was to foster commercial cooperation and cultural relations among the American republics.

Over time, Rockefeller engaged in different ways with the group of Brazilians involved in the donation to Brazil, which included names such as Rodrigo Melo Franco de Andrade, Assis Chateaubriand, Sérgio Milliet, Rino Levi, Ciccillo Matarazzo, Yolanda Penteado and Pietro Maria Bardi. The gift allowed Rockefeller to relate to the Brazilian elite in a friendly way, without the impression of it being enforced by the US, in an initiative of so-called “soft power.”

Jacob Lawrence, the only black artist to contribute to the collection, was then 29 years old and the youngest artist in the group that supposedly represented the new American art, curated by Dorothy Miller. The MoMA curator and partner of Alfred Barr, the emblematic former director of the museum, gave great attention to emerging artists when selecting the works. However, the rookie status attributed to Lawrence is debatable, as he had already gained considerable prominence at the time the set of works was acquired.

Another occasion in which his work appeared in Brazil was the first São Paulo Biennial in 1951, when three of his paintings were exhibited as part of the US production. Tombstones addresses the black urban experience and is marked by the symbolism of birth, adulthood, death and spiritual awakening. Slums, 1950, from the Elizabeth Marsteller Gordon Collection, stirs feelings of aversion by bringing to the foreground cockroaches and flies framing an overcrowded urban landscape. MoMA’s Sedation, painted in 1950 following his one-year stay in a psychiatric institution, features patients contemplating pills, a reflection on the benefits and consequences of using medication. It is worth noting that in 1991, Samella Lewis, author of landmark works of African American art history, held at MAC USP the exhibition Jacob Lawrence: An American in Harlem.

The historian Patricia Hill described Jacob’s production as akin to expressive cubism, i.e., he uses “cubism as a vehicle for important social commentary.” Jacob Lawrence declared several times his interest in Mexican muralists. A term frequently linked to his work is social realism, which overlaps with the end of the Harlem Renaissance in the second half of the 1930s and extends throughout the 1940s. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal included the WPA Federal Art Project, a national program dedicated to supporting artists which privileged figurative art with subject matters related to American history and the working class. It benefited a relatively high number of black artists, and Lawrence was linked to the program for a period. By addressing street scenes, characters and historical scenes from viewpoints that differed from official versions, Jacob Lawrence created narrative paintings that were effective as social commentary. His works feature a certain degree of abstraction without losing sight of human figures, aiming to offer works of art that could be understood by the people.

The MAC USP painting work invites us to learn more about the production of African American artists, especially the works by Jacob Lawrence, seeking what he can reveal to us about the Afro-Atlantic world and ourselves.

References

TOLEDO, Carolina Rossetti de. As doações Nelson Rockefeller no acervo do Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo. (Dissertação de mestrado) . Universidade de São Paulo, 2015.

LAWRENCE, Jacob, and Patricia Hills. Over the Line: the Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence. University of Washington Press, 2000.