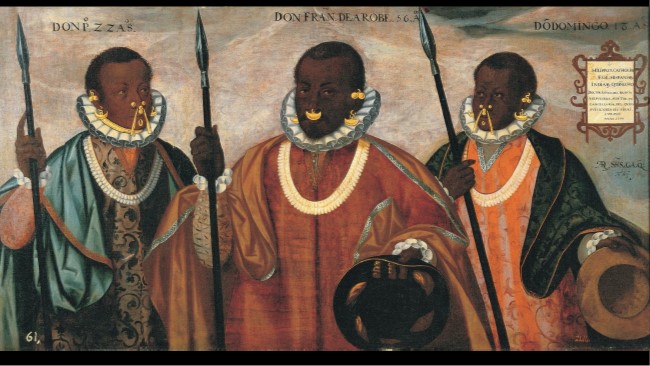

This title has two very recent quotes to which I shall later refer. I begin however, with a magnificent portrait of Don Francisco de Arobe and his two sons Don Pedro and Don Domingo, from the coastal community of Esmeraldas of present-day Ecuador that belongs to the Prado Museum in Madrid (Fig. 1). For Spaniards, the identity of the sitter and the artist are not the indexical signifiers of the work although the names of the sitters and the artist are clearly inscribed on the painting. Race is the contemporary indexical signifier of this portrait. It is often labeled merely as a painting entitled Los Mulatos de Esmeraldas, even in essays and exhibitions in which the scholar or curator discusses the subject and the painter by their names. Unlike any other sixteenth-century portrait in the Prado’s collection for which the subject is clearly identified, race is the determining pictorial element that indexically marks the subject of the painting for the viewer.

Legenda

Legenda Andres Gallque. Portrait of Don Francisco and his sons’ Don Pedro and Domingo, oil on canvas, The Prado Museum on loan to The Museum of the Americas, Madrid.

That is, the identities of those who were painted, who painted it, and who commissioned it are all inscribed on the painting itself, but are not consider as critical. Yet we know that it was painted and signed by Andrés Sánches Gallque, a native painter in 1599 and commissioned by the Juan de Sepúlveda y Barrio from the Audiencia in Quito. He commissioned the painting to be sent to Philip III, and it was received in Madrid. The signed portrait is of three independent named individuals just as Titian’s signed portraits are of named individuals. Don Francisco’s and his sons’ portrait was placed in the palace as were other portraits including those of the Inca painted by native artists in Cuzco, as well as portraits of Charles V and Philip II painted by a native artist in Venice. I and others have written about this fascinating portrait of Don Francisco and his sons and its history, names and meaning can be had in these publications (COMMINS, 2013, p. 118-145). What is important for this essay is the fact that this painting is one of the most requested and exhibited works internationally of any painting held in Spanish collections and an enlarged detail featuring Don Pedro is the key image greeting visitors to an 2021-2022 exhibition at the Prado Museum entitled Torna Viaje. The large photo is carefully cropped to eliminate his name (Fig. 2). I will therefore return to its more recent collection and exhibition history of the nineteenth, twentieth and twenty-first centuries as they demonstrate a clear set of neo-colonial and racist positions within modern Spanish history and their re-emergence in contemporary Spanish cultural politics.

Legenda

Legenda Andrés Sánches Gallque. Detail of the Portrait of Don Francisco, Don Pedro and Don Domingo, enlarged photo at the entrance of the Prado’s exhibition Torna Viaje, 2021. Photo Alejandro de la Fuente.

To understand the broader context, I turn to the exhibition of Peruvian contemporary artist, Sandra Gamarra, which opened in a Madrid gallery September sixteenth, 2021 (Fig. 3) (WEINER, 2021 a). Sandra Gamarra is an international and highly respected multi-media artist, who has exhibited in the Berlin Biennale, the XXIX Bienal de Sao Paulo, in the Istituto Italo-Latino Americano (IILA) Pavilion, in the 53 Venice biennale, in la XI Bienal de Cuenca, and her works have been exhibited in MACBA, (Barcelona, España), Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, (Madrid, Spain), MUSAC, (León, Spain), Museum of Contemporary Art-Lima, (Lima, Perú), Contemporary Art Museum in Tokyo (Japan) and the Tate Modern (London). In Madrid she created an installation called Buen Gobierno in the Sala Alcalá 31, a space that belongs to the city of Madrid. Her installation occurs within the Madrileño month long celebration Hispanidad 2021. I shall return to the political history of the Spanish concept of Hispanidad at the end of this essay. However, as the world seemingly moves toward two antithetical political positions of neo-fascism/authoritarianism/demagoguery and de-colonization/democracy/critical thinking and expression, whether in the United States, Brazil, Peru, England, Italy, and Spain to give obvious and explosive examples, Hispanidad is an historical term that has incredible racist baggage that the extreme right is happy to carry.

Legenda

Legenda Announcement of the Opening of Buen Gobierno by Sandra Gamarra, September 16th, 2021.

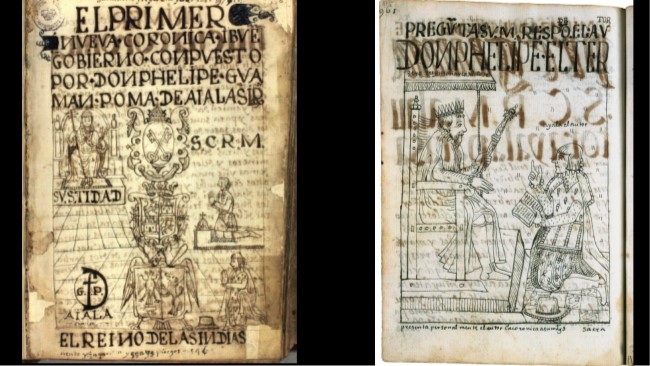

Buen Gobierno is a phrase to which most Peruvians know what it refers. It is a part of the title of the illustrated manuscript created by the Andean author Don Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, finished in 1615 and which the author sent to Philip III (Fig. 4a, b).

Legenda

Legenda Guaman Poma de Ayala. Frontispiece with the portraits of Pope Paul V, King Philip II and Prince Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno, 1615, ink on paper, courtesy of the Royal Danish Library GKS 2232 4º, page 1.

Guaman Poma de Ayala. Ask your Majesty, the author Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno, 1615, ink on paper, courtesy of the Royal Danish Library GKS 2232 4º, page 971 (965).

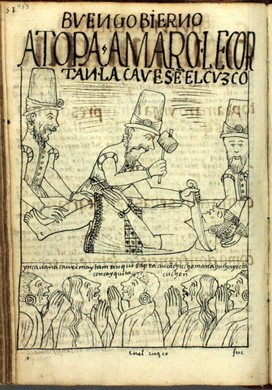

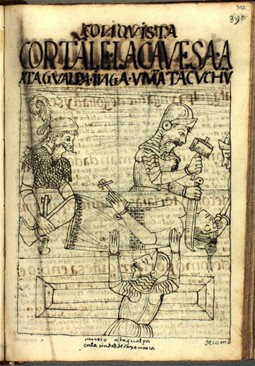

Gamarra gives her exhibition the words that appear in manuscript’s frontispiece emblazoned with the title El primer nueva coronica i buen gobierno. Here one also sees the portraits of the Pope, King of Spain and the author’s portrait accompanied by their coats of arms which form the central vertical axis of the composition. A later critical drawing for understanding the author’s intent of the manuscript depicts the author’s imagined meeting with Philip III. A self-portrait of Guaman Poma kneels before the king with his manuscript, open to the text, as he gestures with his right index finger pointing upward. This gesture is a common deictic figure drawn in the margin of a manuscript or book indicating the importance of a certain passage for the reader. Here it emphasizes the importance of creating an intimate dialogue of inquiry by Philip III and the response by Guaman Poma. Written at the bottom of the drawing, Guaman Poma identifies himself as the author and says that he personally presented the Corónica to his majesty. The manuscript minus the author arrived in Madrid. It probably never was really read by many if anyone, but certainly not by Philip III. Eventually, it was given as a gift and ended in the royal Danish library where it remained unstudied until the 20th century. Since then it has become a critical part of Peruvian social and political consciousness in part because the Andean author in text and image outlines Spanish abuses, beginning with the regicide of the Inca leaders, Atahualpa and Tupac Amaru as one can see in Guaman Poma’s pen and ink drawing of their savage beheading (Fig. 5a & b).

Legenda

Legenda Guaman Poma de Ayala. Atahualpa execution at Cajamaraca by Pizarro and others, Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno, 1615, ink on paper, courtesy of the Royal Danish Library GKS 2232 4º, page 390 (391).

Legenda

Legenda Guaman Poma de Ayala. Execution of Manco Capaca by Viceroy Toledo at Cajamaraca in Cuzco, Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno 1615, ink on paper, courtesy of the Royal Danish Library GKS 2232 4º, page 453 (385).

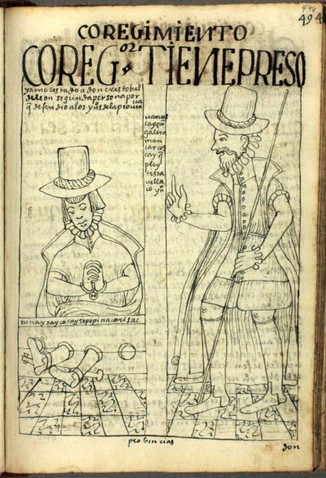

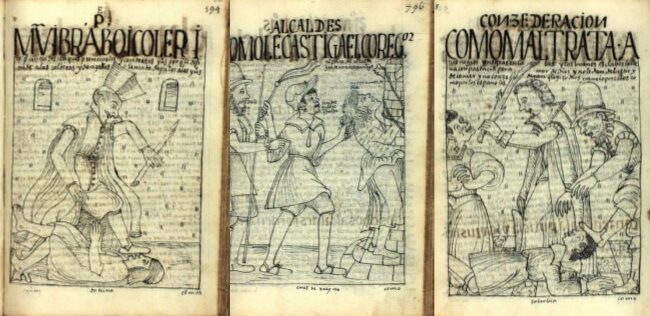

The images continue in terms of depicting the different civil wars that ravaged the new viceroyalty, as well as viceregal government, commerce, education, and evangelization. But all these categories are interspersed with images of colonial violence toward Andeans and Africans. As one can see in one drawing, the Corregidor orders the punishment of the curaca or leader of the community for not producing the chickens that the Corregidor had demanded by placing him in stocks. (Fig. 6).

Legenda

Legenda Guaman Poma de Ayala. Corregidor keeps Don Cristobal, Curaca and a Prisoner, Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno 1615, ink on paper, courtesy of the Royal Danish Library GKS 2232 4º, page 494 (385).

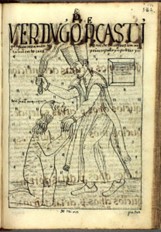

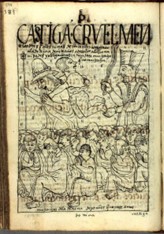

Corregidores, encomenderos, and priests are seen in the same violent disciplinary light whipping the naked bodies of adults and children or hanging others from a picota (a column placed in the plaza) as well as performing other cruel and violent acts toward Andean peoples (Fig. 7a, b, c)

Legenda

Legenda Guaman Poma de Ayala. Atahualpa at Cajamaraca with Pizarro and Translator Felipe, Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno 1615, ink on paper, courtesy of the Royal Danish Library GKS 2232 4º, page 384 (385).

Legenda

Legenda Guaman Poma de Ayala. Atahualpa at Cajamaraca with Pizarro and Translator Felipe, Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno, 1615, ink on paper, courtesy of the Royal Danish Library GKS 2232 4º, page 384 (385).

Legenda

Legenda Guaman Poma de Ayala. Atahualpa at Cajamaraca with Pizarro and translator Felipe, Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno, 1615, ink on paper, courtesy of the Royal Danish Library GKS 2232 4º, page 384 (385).

Finally, we can see that the racial components of the colonial hierarchy are on display in which a Spaniard beats an Andean, an enslaved African man whips an Andean on behest of the orders of a Corregidor, or a Spanish couple beat their African slaves/servants. From this Andean political point of view the abuses of the Spanish government and people are insufferable. Guaman Poma claims that they the Andeans were always and already Christian and that Andeans had accepted the rule of the Spanish king so the Andeans should be left to rule under the king’s protection and a merciful Church that would be overseen by the Andeans (Figure 8a, b and c).

Legenda

Legenda Guaman Poma de Ayala. A Native Parishioner is Beaten to Death for Defending Unmarried Andean Women and Maidens from the Lascivious Priest, Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno, 1615, ink on paper, courtesy of the Royal Danish Library GKS 2232 4º, page 594 (608).

Guaman Poma de Ayala. The Royal Administrator Orders an African Slave to Flog an Indian Magistrate for Collecting a Tribute that Falls two Eggs Short, Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno, 1615, ink on paper, courtesy of the Royal Danish Library GKS 2232 4º, page 796 (810).

Guaman Poma de Ayala. How the Spaniards Abuse their African Slaves, Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno, 1615, ink on paper, courtesy of the Royal Danish Library GKS 2232 4º, page 925 (939).

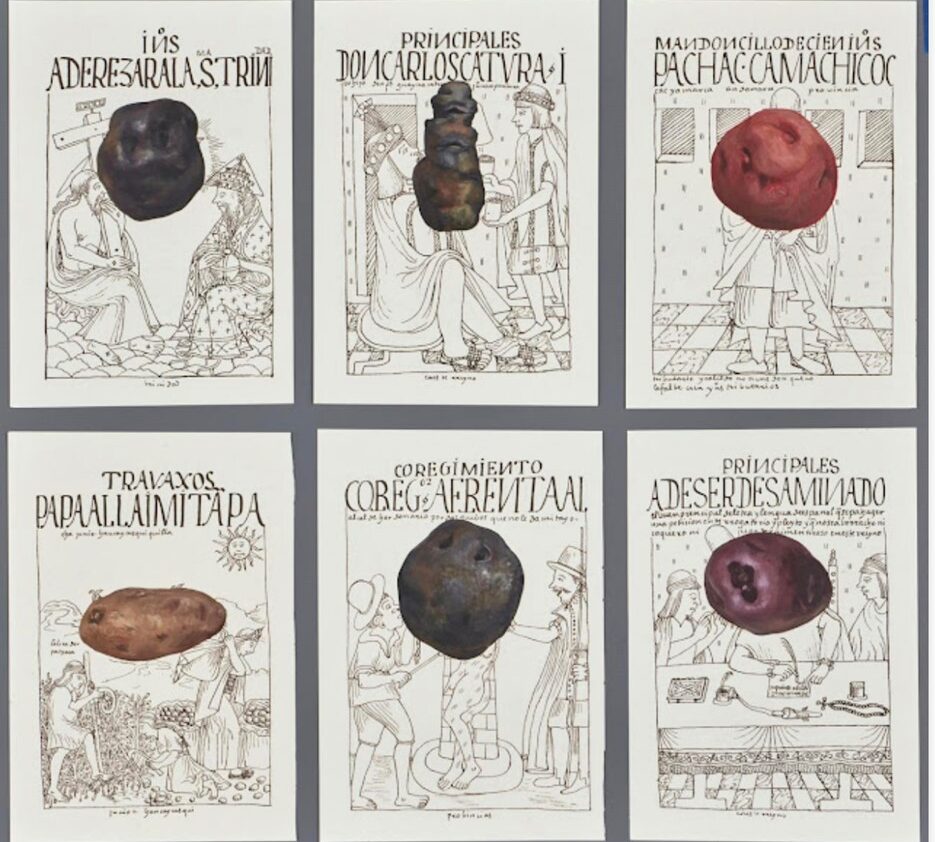

This of course was never going to happen. And so, Sandra Gamarra’s installation took up this historical theme with a variety of different images such as Cuando las papas queman in which the photo of a potato, the greatest Andean gift to the world’s nutrition, is superimposed on a copy of Guaman Poma’s images (Fig. 9). What precisely the phrase means is ambiguous, intentionally so, I suppose. It can mean “things heat up”, “When the chips are down,” or “when it’s on the line.” It all depends on the semantic context in which the phrase appears. The scenes chosen from Guaman Poma are also radically different and therefor may shift the meaning of the phrase for Gamarra and her public. The different variety of potatoes superimposed upon Guaman Poma’s images implies both differences as well as the commonality of Peruvian life and experience. Catholic doctrine of the Trinity, drunkenness of an imposter, harvesting potatoes, torture of an Andean by an African who obeys the instructions of a Spaniard, and indigenous literacy of a community leader on behalf of one of his community’s members are all subjects of the images that Gamarra has picked and onto which a different type of potato has been placed.

Legenda

Legenda Sandra Gamarra Heshiki. Cuando las papas queman, 2021.

Gamarra also included in her exhibition images of pre-Hispanic ceramics from Moche sites that were conceded in the colonial period to Spaniards to mine for gold where the ancient dead had been interred (Fig. 10). These are “portrait” vessels implying the presence of pre-Hispanic people just as the colonial painted portraits imply the presence of the different peoples and experiences of the viceroyalty of Peru.

Legenda

Legenda Sandra Gamarra Heshiki, Huacas.

She also included meticulous copies that she made of the only series of Castas paintings from Peru commissioned by the Viceroy Manuel de Amat y Juyet to be sent to the Prince of Asturias and future king of Spain, Charles IV. Both the series of the Castas commissioned by Amat and the Portrait of Don Francisco de Arobe and his sons by Sánches Gallque were also exhibited together in el Museo Arquelógico Nacional at the beginning of the 20th century.(Fig. 11). (USILLOS, 2012, p.58)

Legenda

Legenda Sandra Gamarra, Castas.

Gamarra interacts with the Castas series by copying from the originals which are still in the collection of Anthropology in Madrid (Fig. 12).

Legenda

Legenda Sandra Gamarra copying the Castas series.

Her work is original, engaged, and provocative, and there are many more elements to the exhibition. It was meant to challenge the norms imposed by fallen imperial powers who cling to an idealized past of Christian beneficence. This apologetic position has never faded, but instead it is re-emerging throughout the world in opposition to the idea of de-colonization of history and culture. For example, most recently the Mexican historian Fernando Cervantes employed in the United Kingdom has published recently a well-received apology of the conquest and imposition of Spanish viceregal rule concluding with the passage:

The result, to cut a long story short was three centuries of stability and prosperity. Of course, this was not the kind of prosperity that we would nowadays find readably comprehensible, accustomed as we are to insist on the need for relentless economic growth. But the viceregal system, curiously enough is much closer to the many and increasingly persuasive attempts to find solutions to the environmental crisis, a crisis brought about precisely by our obsession with continual economic growth. From this viewpoint there is still much to be learned from the legacy of a group of men who, whatever their myriad of failures and shortcomings, deserve to be judged from a more sympathetic perspective than the one that has hither to condemn them uncritically and on the basis of simplistic and even mendacious caricatures (CERVANTES, 2020, p. 356-357).

Cervantes defense of the Spanish conquest and the benefits of Spanish rule as well as calling some its chief critics such as Bartolomé de las Casas and others as being simplistic and liars is hardly original, in fact is not a new argument at all. One need only read the title of chapter XVI “El Cuzco. – Descripción de la ciudad. – Defensa del conquistador. – Inhumanidad de los indios. – El trabajo de las minas. – Reseña de las conquistas mejicana y peruana. – Defensa del autor. – Opinión del visitador” in Concorlorcorvo’s 1773 El Lazallio de ciegos to understand that the historian Cervantes has simply marshaled more facts for a centuries-old defense of the Spanish conquest and the accusation of an uncritical use of las Casas and other defenders of the indigenous peoples. Concorlocorvo wrote:

“A los piadosos eclesiásticos que destinó el gran Carlos Primero, Rey de España, les pareció que este trato era inhumano, y por lo mismo escribieron a la corte con plumas ensangrentadas, de cuyo contenido se aprovecharon los extranjeros para llenar sus historias de dicterios contra los españoles y primeros conquistadores.” (CONCORLORCORVO, 1773, p. 268-269)

Cervantes’s defense of the Conquest and subsequent rule against any criticism about colonial violence and racism was enforced by the city government of Madrid “La Comunidad de Madrid” which immediately moved to censor the terms of “racismo” y “restitución” that appeared in Sandara Gamarra’s exhibition as they questioned the Madrileño idea of the true meaning of “la Hispanidad.” Not only did the Consejería de Cultura order the removal of these terms from the pamphlet that was to be received by the public but the exhibition was subsequently excluded from the “festival Hispanidad 2021.” What bothered la consejera de Cultura de la Comunidad de Madrid, Marta Rivera de la Cruz were precisly the words “racismo” y “restitución”. The team of the “consejera” demanded that the artist as well as the comisario, Agustín Pérez Rubio, remove the terms from public view as they were disturbing the narrative of Hispanidad. Similar thought control of disturbing historical reckoning is occurring throughout the world. For example, the Florida legislature introduced a bill that legislates the following: “An individual, by virtue of his or her race or sex, does not bear responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex. An individual should not be made to feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race.”.

A exposição foi aberta uma semana depois sem vestígio das palavras, mas a instalação não mudou. Um pouco depois, no entanto, o festival Hispanidad abriu sem incluir a exposição de Gamarra, Buen Gobierno. Gamarra disse: “Precisamos retirar essas duas palavras. Não queriam vê-las na apresentação da mostra e entendo que possam ser palavras duras, mas são dois termos em debate no mundo todo. Não houve qualquer outra intromissão na mostra, mas não ficamos surpresos com essa posição… Fico muito triste” (WEINER, 2021 b).

The exposition opened a week later without a trace of the words, but the installation did not change. Only slightly later, the festival of Hispanidad opened without including Gamarra’s exhibition Buen Gobierno as being a part of it. Gamarra said: “Tuvimos que retirar esas dos palabras. No querían verlas en la presentación de la muestra y entiendo que pueden ser dos palabras duras, pero son dos términos a debate en todo el mundo. De ninguna manera hubo más intromisión en la muestra, pero no dejó de sorprendernos esta posición… Me entristece mucho” (WEINER, 2021 b).

At the same time that this farse by the right-wing government was unfolding in Madrid, the President of the city of Madrid Isabel Díaz Ayuso, who is also a member of the extreme right in Spain, took aim at the issues of de-colonization or what she so quaintly called “historical revisionism” with her remarks at the Hispanic Society of America in New York City on September 27, 2021.

I do not employ the term fascist ideology lightly. Spain had the longest enduring fascist government in history, surviving into the 70’s, and I will return below to its politics under Franco and those of Madrid today as the rhetoric of Hispanidad of then and now is identical.

The Hispanic Society of America is a rather obscure museum in New York, one that is deeply appreciated, but one that is seldom visited. There, among other riches, hang the portraits of Spanish elite by Diego Velásquez and Francisco Goya along with American portraits by painters such as Campeche from Puerto Rico and they are all proudly displayed together on their webpage (Fig. 13). This kind of inclusion is not to be had in Spain as we shall see, and it is not a part of the fascist notion of cultural politics of Hispanidad enacted in the early 1940s by Franco.

Legenda

Legenda Internet Page of the Hispanic Society with their Portraits painted by Velásquez, Goya, and Campeche.

Hispanic Heritage at the Hispanic Society understands it as a wider ranging notion of a diverse heritage as was being celebrated in the museum as represented on its webpage as Heritage Month (Fig. 14) in the same month that Isabel Díaz Ayuso delivered her fascist diatribe.

Legenda

Legenda Internet page of the Hispanic Society announcing the celebration of the Hispanic Society.

And while the public in New York city could not actually go to the museum as it was closed for renovation, the museum opened its doors to Díaz Ayuso, receiving her in its Joaquín Sorolla’s Vision of Spain Gallery (Fig. 15). There she made herself available for an interview with the Wall Street Journal’s Opinion editors, a group that is also on the extreme right of American politics and culture.

Legenda

Legenda Díaz Ayuso on September 27th seated below one the paintings of Joaquin Sorolla’s series Vision of Spain at the Hispanic Society, commissioned by Archer Huntington 1913–19.

Organized as part of a weeklong US trip by Díaz Ayuso with stops in New York and Washington, DC, the interview was followed by an impromptu speech delivered to about a dozen Hispanic Society representatives, according to the Spanish newspaper El País (SÁNCHEZ-VALLEJO, 2021). Díaz Ayuso spoke favorably of US-Spain relations but she then launched into a diatribe against “revisionist, dangerous, and pernicious” ideologies that she believes are leading to a “cultural regression.” Calling for a “defense of real history,” she criticized anti-colonial and Indigenous movements that challenge heroic narratives of the Spanish conquest as a “dangerous current of communism through indigenismo that constitutes an attack against Spain” (SÁNCHEZ-VALLEJO, 2021)

When she was asked by El País journalist María Antonia Sanchéz-Vallejo for her opinion on the New York City Department of Education’s decision to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day, Díaz Ayuso said the move was “fatal.” On the following Wednesday, Díaz Ayuso delivered similar at the headquarters of the Organization of American States (OAS) in Washington, DC:

Why are we revising the history of Spain in America and questioning Hispanicity 500 years later, when all it did from its origins was bring universities, civilization, and the West to the American continent, values sustaining prosperous democracies to this day?” (LISCIA, 2021)

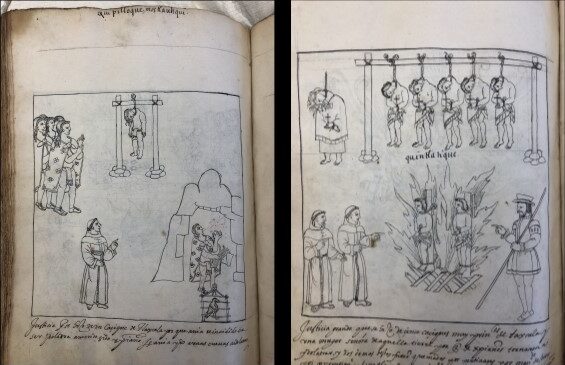

Díaz Ayuso’s visit occurred in the middle of Hispanic Heritage Month in Madrid, observed from September 15 to October 15 as we have already seen. This is in concert with the conservative concept of Hispanidad that brought censorship to Sandra Gamarra’s words by the Consejo. And just so one does not think Guaman Poma’s images are the aberrant work of an angry Andean and that Gamarra’s reference to and use of them is a fiction in the face of the great and beneficent civilization that Hispanidad bestowed on the peoples of America, it is important to see just a few other images that depict the views and experiences of the people who received that civilizing mission. The vast majority are from Viceregal/colonial Mexico because of the pictorial traditions continued as a medium of record. In the viceroyalty of Peru, one finds the evidence in written form from trials and other testimonies. The first two images (Fig. 16) are from a manuscript entitled Descripcion de la ciudad y Provincia de Tlaxcala de la Nueva España, which was given to Philip II in Madrid in the 1570’s by the community who produced it. The Tlaxcalans were the crucial allies of Hernán Cortés and his army but they were still subjected to religious persecution as can be seen in two pen and ink drawings of the leaders of the Tlaxcala community who were hanged or burned at the stake for practicing their own pre-Hispanic religion.

Legenda

Legenda Diego Muñoz Camargo. Descripción de la ciudad y provincia de Tlaxcala Justice adminstered to Aposates in Tlaxcala, Descripción de la ciudad y provincia de Tlaxcala Sp Coll MS Hunter 242 (U.3.15) Glasgow University Library.

The second is an image (Fig. 17) of an execution that took place in Coyoacán, the residence of Hernán Cortés who is depicted above a large mastiff. It is unleashed to tear at the neck of a bound indigenous religious leader from Cholula, one of the most holy cities in Ancient Mexico. Six other leaders of the surrounding communities of Coyoacán are also bound and chained together awaiting their execution by the wolfhound. The image records in the pictorial idiom of Mesoamerica an “…execution inflicting maximum terror, both to its victims and witnesses.”.

Legenda

Legenda Anonymous. Manuscrito del aperreamiento. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

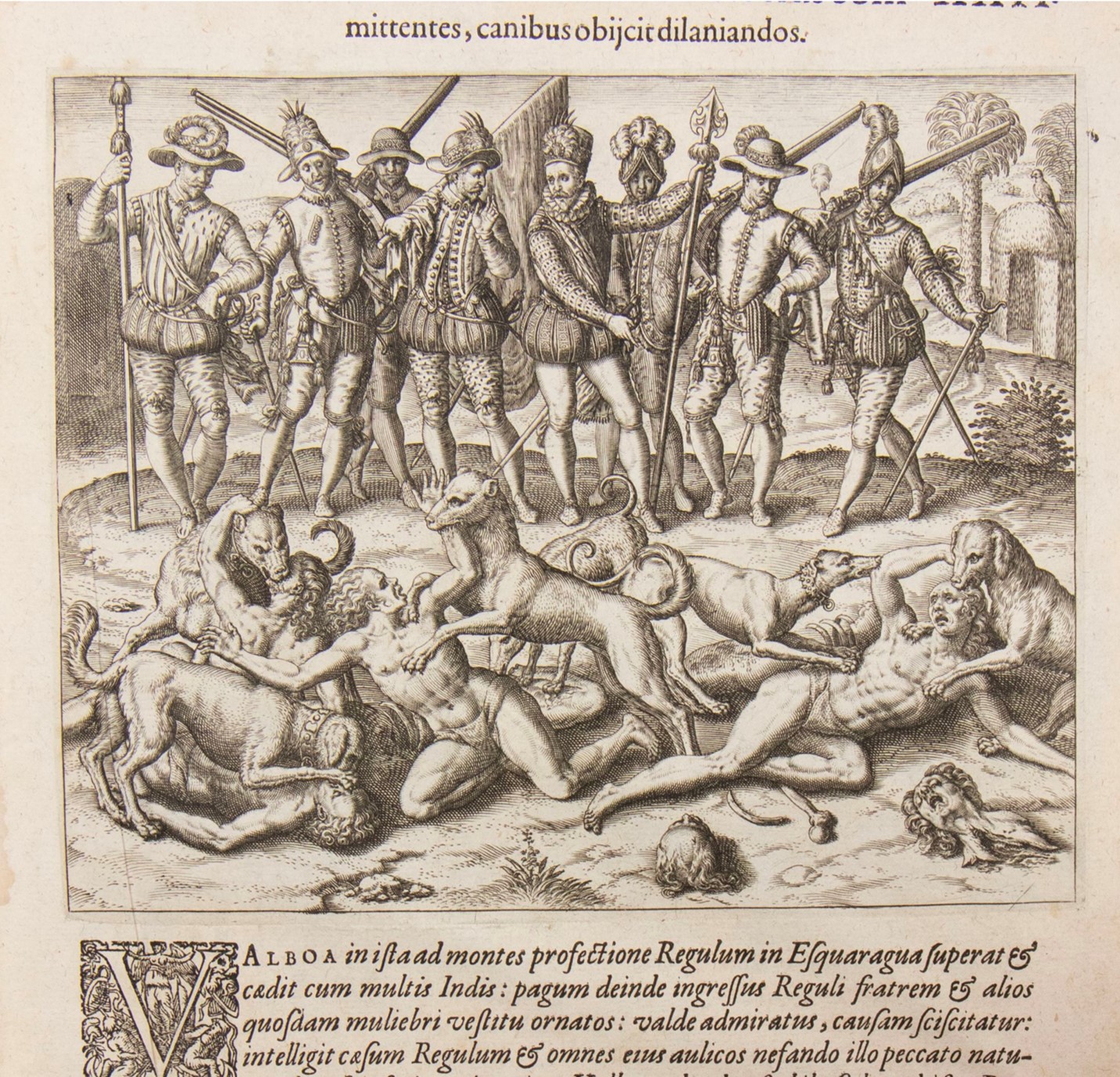

This Mexican image substantiates Bartolomé de las Casas’s remark about these “wild dogs that would savage a native to death as soon as it look at him, tearing him to shreds and devouring his flesh as though he were a pig. These dogs wrought havoc among the natives and were responsible for much carnage.”. Theodore de Bry’s illustrations of a later edition of Las Casas’s Brevissima Relación as well as Girolamo Benzoni’s 1565 illustrated text Historia del Mondo Nuovo concerning Balboa’s torture of sodomites in Panama which was reprinted and illustrated in de Bry’s Americae Pars Quarta are European images of the same subject (Fig. 18). They treat the unleashing of dogs on native peoples, in a late Renaissance classical figures and while the compositions and style of the Mexican and European images are radically different, they are complementary in the horror of the act but done for radically different reasons.

Legenda

Legenda Theodore de Bry. Balboa tortures Sodomites in Panama Americae Pars Quarta copper engraving, 1592, 16×20 cm 1594.

In a different Mexican codex we see the torture and burning of Mexicans for not rendering the gold that was promised to the Spanish overlords (Fig. 19). In fact, colonial imagery produced by indigenous artists for themselves and/or for legal cases are full of images of torture and slaughter. These are new images. There are images of human sacrifice and bloody battles such as at the Maya murals at Bonampak or Moche low relief sculptures at Huaca de la Luna, but these colonial images by Guaman Poma in Peru and the painters of Mexican manuscripts address a different violence and they are new. But what is important to realize is that the pre-Columbian violent images as well as colonial images depicting human sacrifice and war are neither censored nor criticized but used by contemporary scholars and politicians to advance their claim of the Christian civilizing mission initiated by Hernán Cortés and other Spaniards and that such new colonial images of Spanish torture and murder are merely the artifice of the defaming “Black Legend” (CERVANTES, 2020, p. 151).

Legenda

Legenda Anonymous Codex Tepetlaoztoc. [Codex Kingsborough], A.D. 1554. Mexico, Tepetlaoztoc. Nahua. Paper, pigment, closed: 11 3/4 x 8 7/16 in, 1554. Folio 8r and 9r British Museum, AM2006, DRG. 13964.

These images and those by artists such as Sandra Gamarra are not a renewed or new black legend that Díaz Ayuso claims them to be. They are a part of the history of what really happened to those to whom it happened. Yet, from the Spanish point of view this kind of discipline was the necessary basis on which human rights emerged in America as recently claimed by King Philip IV in Puerto Rico: “Spain brought with it its language, its culture, its creed and with all this it brought values and principles such as the foundations of international law and the concept of universal human rights” (ATALAYAR. s.d.).

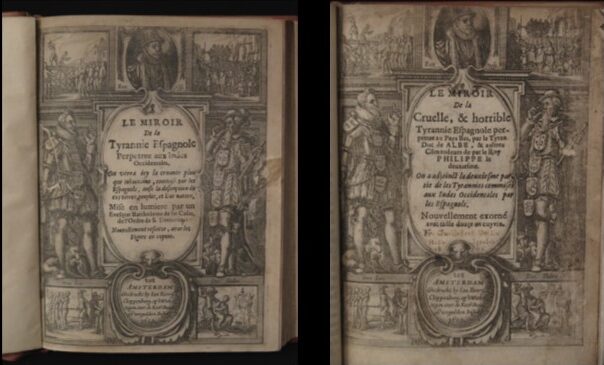

Of course, there is the Spanish black legend, but that comes as a result of the strife in Northern Europe, the religious and political antagonisms and most especially with the violence that took place in the liberation of the Low Countries. This European violence was directly paralleled with what had already occurred in America as manifested in the 1620 publication of the tyranny of the Spanish in which what happened in America, as based on a partial republication Bartolomé de las Casas’s Brevissima Relación (every apologist’s for “Hispanidad” bête noire). It was used to characterize the cruel tyranny of the Spanish presence in America as being the forerunner for what would happen in the Low Countries as described in the jointly published abbreviated version of Oorsprong en voortgang der Nederlandtscher beroerten (Origin and progress of the disturbances in the Netherlands) by Johannes Gysius (Fig. 20).

Legenda

Legenda Frontispieces of the joint publication Le Miroir de la Tyrannie Espagnole and Le Miroir de la Cruelle & Horrible Tyrannie Espangole, Amsterdam: Ian Evertss. Cloppenburg, 1620.

The more recent recognition of Spanish atrocities in America is understood by the extreme racism of the right wing in Madrid as having a different parallel: “Indigenism is the new communism” as Díaz Ayuso’s claimed. Communism is here the political rallying cry of the remnants of Franco’s oppressive state to which they want to return. The equation between indigenism and communism is the threat of state incarceration, torture, and execution as perpetrated first in America and then in Spain under Franco. One need only think of the Valle de los Caidos built by forced convict labor many of whom were political leftist/communist prisoners. Many died there, just as so many natives died in the forced labor of Muso, Potosí, and elsewhere as the veins of America were cut open literally, bleeding gold and silver and blood in the name of the Christian god of Catholic Spain.

Much like Donald Trump, whom she admires, Díaz Ayuso is not the brightest bulb. She has no understanding of history or social issues, but she is certainly eager to cast discriminatory comments, such as her suggestion that cases of COVID-19 in Spain were being driven by the “way of life” of the country’s immigrant population. And only a few days ago, Díaz Ayuso publicly denounced Pope Francis’s apology for the Church’s role in the Spanish conquest. The text that the Pope delivered in Santa Cruz Bolivia in 2015 is the antithesis of the extreme defense of the Church and Conquest as articulated by Fernando Cervantes and many others in Spain. The Pope delivered this encyclical::

El colonialismo, nuevo y viejo, que reduce a los países pobres a meros proveedores de materia prima y trabajo barato, engendra violencia, miseria, migraciones forzadas y todos los males que vienen de la mano… precisamente porque al poner la periferia en función del centro les niega el derecho a un desarrollo integral. Y eso hermanos es inequidad y la inequidad genera violencia que no habrá recursos policiales, militares o de inteligencia capaces de detener.

Digamos NO entonces a las viejas y nuevas formas de colonialismo. Digamos SÍ al encuentro entre pueblos y culturas. Felices los que trabajan por la paz.

Y aquí quiero detenerme en un tema importante. Porque alguno podrá decir, con derecho, que «cuando el Papa habla del colonialismo se olvida de ciertas acciones de la Iglesia». Les digo, con pesar: se han cometido muchos y graves pecados contra los pueblos originarios de América en nombre de Dios. Lo han reconocido mis antecesores, lo ha dicho el CELAM El Consejo Episcopal Latinoamericano y también quiero decirlo. Al igual que San Juan Pablo II pido que la Iglesia y cito lo que dijo Él «se postre ante Dios e implore perdón por los pecados pasados y presentes de sus hijos» (6). Y quiero decirles, quiero ser muy claro, como lo fue San Juan Pablo II: pido humildemente perdón, no sólo por las ofensas de la propia Iglesia sino por los crímenes contra los pueblos originarios durante la llamada conquista de América.

The point here is that Hispanidad as it is being celebrated right now in exhibitions in Madrid is intended to celebrate a long-gone empire and colonial set of relations that seeks to keep dominion over alternative voices as to what that means, including that of his predecessor Pope Alexander VI, whose Inter Catedra (1493) gave Spain dominion over America. But what does that mean for the painting with which I began this essay.

I begin to circle back to temporary exposition of Don Francisco de Arobe and his sons through a quick look at the Prado’s history and its very clear case of ethnic aesthetic cleansing. To understand what this means is to read the Prado’s underlying mission as articulated in the official statement celebrating its 200th anniversary: “With an outstanding collection stemming from centuries of art patronage by the Spanish Crown and opened to the public in 1819 by the King Ferdinand VII, here visitors can not only admire the world’s largest collection of Spanish paintings, but also formidable collections of Flemish and Italian paintings, as well as the most complete collection of works by artists such as Bosch, Titian, Rubens, Velázquez, Ribera, Murillo, Goya, and El Greco. The Spanish painting collection spans from the twelfth to the nineteenth century with principal works of artists such as El Greco, Murillo, Zurbarán, Ribera, Sorolla, and, most notably, Goya and Velázquez, the last two of which are particularly brilliant. The incomparable collection of Goya’s works is comprised of more than 140 pieces; additionally, among other famous paintings in the Museum´s Collection are The Family of Charles IV, The Naked Maja, The Clothed Maja, The Second of May, 1808, and The Third of May, 1808, as well as his famous collection of Black Paintings”.

Indeed, from Titian’s majestic Equestrian portrait of Charles V at Mühlberg to Goya’s The Family of Charles IV hang in the Prado as a royal collection of the Spanish nation (Fig. 21). What one does not learn is that originally Titian’s portraits of Charles V at Mühlberg and Philip II offering the Infante Fernando to Victory were displayed with the portraits of the Inca kings that were painted in Cuzco by Andean artists.

Legenda

Legenda Titian. Portrait of Charles V at Mulberg, oil on canvas 1548, Prado Museum.

Legenda

Legenda Francisco Goya. Portrait of Charles IV the Royal Family, 1800, oil on canvas, Prado Museum.

What is not on display are any American paintings that were also transferred with the paintings by Titian, Velázquez, Rubens, Goya and many others to the Prado. One of them is the Portrait of Don Francisco de Robe and his sons (Fig. 1). It is found listed in the Prado inventory as belonging to the Prado, and one need only look at the numbers to the bottom right and left to see the royal palace inventory numbers from the 18th century. But this portrait is not in the Prado on permanent exhibition or even in the storerooms. It does not hang with the paintings of Velázquez or Goya or Titian. Rather it is now in the Museo de America, a seldom visited museum created in 1944 to enhance the idea of Spain and its dominion overseas by Franco. All the American paintings that were kept in the royal collection and given in 1819 were expunged from the European paintings, now so proudly kept in the Prado to celebrate Spain’s Europeanness. nstead, the Don Francisco’s portrait was transferred as a loan to El Museo Arqueológico Nacional. There it remained and was exhibited until 1941 when it was sent to the newly created Museo de América, but which did not open its doors until 1964. The intent of moving the American paintings and as well as most of them other things from America in the El Museo Arqueológico Nacional to the Museo de América was to promote a “Hispanidad” based upon separation and European superiority. The roots of its formation were, as was stated by the José Ibáñez Martín, el Ministro de Educación Nacional: “se hace más evidente la presencia de América en la nación española, estrechando los lazos de unión, que siempre existieron, pero que hoy evidencian una comprensión y una hermandad entre las naciones que componen la Hispanidad”. The minister made clear that the intent was to combat “leyenda negra” and to point out “la obra de España en América”. There Spain “fomentó también la minería y la industria, creó ciudades, puso, en fin, en innumerables cosas la huella de su espiritualidad. Ejemplo expresivo y magnifico de la obra española en América es la maravillosa arquitectura colonial, símbolo en piedra de dos razas que se unen”.

As Georg Krizmanics has written recently, the foundation of the Museo de América was originally laid out in 1941 as anti-US institution, and it was used to promote right-wing terms and their ideologies such as fascism and Nazism and their concept of “Hispanidad”.

It is important to remember that the Valle de los Caidos was begun at the same time, and it continues to be a venerated site by the extreme right wing. Krizmanics goes on to write that “Las políticas exteriores franquistas se formulaban en torno a la idea de la Hispanidad y esta ideología de estado tenía tales dimensiones que, por orden,” and that it was “prohibido el libre uso del vocablo ‘hispanidad’, no pudiendo utilizarse industrialmente, como marca comercial o como título de establecimientos” (KRIZMANICS, 2018, p. 39-61). Su significado encerraba un doble concepto que se refería al “conjunto de naciones que integran el mundo hispánico” a la vez que “expresa[ba] su peculiar espíritu y entendimiento de la vida, su común tradición histórica y superior destino universal” (KRIZMANICS, 2018, p. 39-61).

The Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores was mandated to oversee the museum during the early years of the Franco’s dictatorship in order to, “llevar a la práctica la misión […] de asegurar la continuidad y eficacia de la idea y obras de genio español” was “el Consejo de la Hispanidad.” The leaders of the Consejo swore upon taken office “por Dios y Santa María, y por los Evangelios que toco con mi mano, que cumpliré con vigilante cuidado la misión […] de trabajar por la propagación de la Hispanidad”, with this was then manifest “el peculiar espíritu y entendimiento de la vida” of this ideology.

The words of Franco’s minister are today channeled by the Consejo in Madrid and by Díaz Ayuso in particular. We now can also understand why Sandra Gamarra’s work was both censored and excluded from the exhibitions that marked the month of Hispanidad in Madrid. Critical interventions are unacceptable. Rather what we now have at the Prado, as proudly announced, is an exhibit in which a detail of the portrait of Don Francisco and his sons is depicted at the entrance of the exhibition which in English is entitled “Return Journey: Art of America in Spain.” In Spanish, the title Tornaviaje. Arte iberoamericano en España has a peculiar racist resonance. The phrase Tornaviaje has, a possibly unintentional, consonance with one of the racial categories depicted in the Casta paintings of the eighteenth century termed torna-atrás (Fig. 22). In these paintings the hidden aspect of racial mixture is revealed in the offspring of an albino and a Spaniard who is darker than either parent as is depicted in the series created by Miguel Cabrera entitled “From a Spanish father and Albino mother a torna-atrás. Casta paintings, including Cabrera’s picture, connect albinism with black ancestry (KATZEW, 2015). In other words and images, an offspring that has African ancestry can never be European or white, never be Spanish, there is no return. The albino only deceives at first what will be born out in the appearance of their child. In another painting by Francisco Clapera (Fig. 23), the one of the few Spanish born artists painting in Mexico, has one of his sixteen paintings titled “De Torna-atrás, e Indio, Lobo.” The mother, designated as torna-atrás, is African descent and her husband, who is identified Indian, have a child who is designated “lobo”. None of this makes any sense, but it is a picturization of the racial categories that were imposed in the viceregal regime and that Sandra Gamarra explored in her exhibition, as they are racial categories that still operate as a factor of racism in Peru, Mexico, Spain, the United States as well as elsewhere in the world.

Legenda

Legenda Miguel Cabrera. From Spaniard and Albino, Return-Backwards (De español y albino, torna atrás), 1763, oil on canvas, private collection, Mexico.

Legenda

Legenda Francisco Clapera (born in Spain, active in Mexico, 1746-1810). De Torna-atras, e Indio, Lobo, Mexico, about 1775, oil on canvas, Denver Art Museum: Gift of Frederick and Jan Mayer, 2011.428.8

To the curators of the Prado’s exhibition Tornaviaje. Arte iberoamericano en España paintings such as the portrait of Don Francisco and his sons are works that “have lost the history of their story,” which is now being returned. However, the title of the painting as it appears in the Prado’s English online announcement of the exhibition identifies the painting as The Three Mulattos of Esmeraldas (Fig. 24)“. That is, the subjects of the painting, Don Francisco and his sons, still do not have “the history of their story.”

Legenda

Legenda The Prado’s internet announcement in English of the exhibition Tornaviaje. Arte iberoamericano en España.

One must wonder precisely what history will be recovered if one cannot speak about why such histories are not only lost but purged from a cleansed “Hispanidad” as Díaz Ayuso, the Dictator Franco, and the “La Comunidad de Madrid” would have it, for fear that “el indigenismo es el nuevo comunismo” (HUFFPOST, 2021). By equating “indigenismo” to “comunismo” in Spain is to rally the right wing conservatives to defend church and country and to colonialize history in its own heroic image. To de-colonize history is to free it for open and honest assessment as Sandra Gamarra attempted in Buen Gobierno. It is to say the names of people represented as well as those who are not represented. It is to show their faces and bodies and what was done to them. This is the task of artists, curators, and scholars. However today, it is certain that there is real and powerful opposition that will censor and shut down critical thought as is being experienced in Spain and elsewhere as I write. And I do not imagine that Andrés Sánches Gallque’s American portrait of Don Francisco and his sons will ever be permanently re-united with those European portraits by Titian Velasquez, Rubeuns, Goya and other Europena painters that are so proudly on continual display in the Prado. That is, there is no real “Return Journey,” and certainly not in the aesthetic terms of Sandra Gamarra Heshiki’s Buen Gobierno.

References

ANÓNIMO. El Anónimo de Yucay Frente a Bartolomé de las Casas. Edición Crítica del Parecer de Yucay [1571]. In. PÉREZ, Fernández (ed). Regionales Andinos Bartolomé de las Casas. Cusco: Centro de Estudios, 1995, p. 158-60.

ATALAYAR. s.d. Available: https://atalayar.com/en/content/king-felipe-vi-defends-spains-legacy-puerto-rico. Accessed: January 28th, 2022

BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS. Breuissima relacion de la destruycion de las Indias. Sevilla: En casa de Sebastian Trugillo impressor de libros. A nuestra señora de Gracia, 1552.

CERVANTES, Fernando. Conquistadores: A New History of the Spanish Conquest. London: Viking, 2020.

COMMINS, Tom, Mirrored Reflections: Spanish Iconoclasm in the New World and its Reverberations in the Old,” El Gran Debate Sobre las Imágenes: La “MONARQUÍA CATÓLICA” y su Imperio Atlántico, Casa de Velasquez, Madrid, May 11, 2017,

COMMINS, Tom. De Bry and Herrera: ‘Aguas Negras’ or the Hundred Years War over an Image of America” in Art, History, and Identity in The Americas: Comparative Visions, Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, UNAM: México, 1994, p. 17-31.

COMMINS, Tom. Three Gentlemen from Esmeraldas: A Portrait for a King. LUGO-ORTIZ, Agnes/ROSENTHAL, Angela (eds.). Portraits of Slaves. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013, p. 118-145.

CONCORLORCORVO. El Lazallio de Ciegos Caminates desde Buenios Aires, Hasta Lima… Gijon: Imprenta de la Rovada, 1773.

DIEL, Lori. Manuscrito del Aperreamiento (Manuscript of the Dogging). A ‘Dogging’ and its Implications for Early Colonial Cholula. Ethnohistory, vol. 58, no. 4, 2011, p. 585-611.

EL PERÓDICO. 2020. Available: https://www.elperiodico.com/es/sociedad/20200915/coronavirus-ayuso-culpa-a-la-inmigracion-de-la-subida-de-contagios-en-madrid-8113913. Accessed: October 20th, 2021.

EL PLURAL.sd. Available: https://www.elplural.com/politica/espana/canto-entra-en-polemica-conquista-america-libero-miles-personas-poder-salvaje-canibal_276130102. Accessed: January 17, 2022.

HUFFPOST 27 de septiembre de 2021. Available: https://www.huffingtonpost.es/entry/ayuso-desde-eeuu-el-indigenismo-es-el-nuevo-comunismo_es_61517c8be4b0016411962b53. Accessed: October 20th

KATZEW, Ilona. Why an Albino? Some Notes On Our New Casta Painting by Miguel Cabrera. Unframed LACMA April 22, 2015. Available:: https://unframed.lacma.org/2015/04/22/why-albino-some-notes-our-new-casta-painting-miguel-cabrera. Accessed: February 7th, 2022.

KRIZMANICS, Georg T. A. El Museo de América de Madrid: ¿un instrumento para la política exterior española? A Contracorriente: Una revista de estudios latinoamericas. vol 15., n. 2, 2018, p. 41.

LISCIA, Valentina Di Liscia At New York’s Hispanic Society, Leader of Madrid Laments Indigenous Movement as an “Attack Against Spain”. Hyperallergic, September 30, 2021. Available: https://hyperallergic.com/681033/leader-of-madrid-laments-indigenous-movement-as-an-attack-against-spain/ Accessed: October 20th, 2021.

MARTÍN, José Ibáñez. Solemne inauguración del Museo de América, ABC, July, 14, 1994.

SÁNCHEZ-VALLEJO, María Antonia. Ayuso Defiende en Nueva York su Gestión “Liberal” de la Pandemia. El País. Sept. 27, 2021. Available: https://elpais.com/espana/madrid/2021-09-28/ayuso-defiende-en-nueva-york-su-gestion-liberal-de-la-pandemia.html. Accessed: October 18, 2021.

The Washington Post Section B. Monday January 17, 2022, p. 1.

USILLOS, Andrés Gutiérrez. Nuevas Aportaciones en Torno al Lienzo Titulado Los Mulatos de Esmeraldas. Estudio Técnico, Rdiográfico e Histórico. 2 Anales del Museo de América, vol. XX, 2012, p. 7-64.

WEINER, Gabriela (a). Opinión, Espejos-Coloniales. El Diario. 22 de septiembre de 2021. Available: https://www.eldiario.es/opinion/zona-critica/espejos-coloniales_129_8328132.html. Acessed: October 16th, 2021.

WEINER, Gabriela (b). Espejos Coloniales. El Diario, 27 de septiembre de 2021. Available: https://www.eldiario.es/cultura/arte/comunidad-madrid-censura-terminos-racismo-restitucion-exposicion-cuestiona-hispanidad_1_8343624.html. Acessed: October 15th, 2021.