In recent years, the reasons why we saw the exponential growth of abstraction in the practice of racialized and dissident artists as a strategy of refusal have outlined my research and curatorship, especially regarding some more recent projects.

As if writing from the future, today I see that how this meeting of ours has taken place has to do with both my exercise of following a group of artists as with the inescapable transformation that these artists have promoted in contemporary art in the last five years. It has also to do with attentively listening to the generative effects sustaining the encounter between theory and practice, which, in the conception of bell hooks’ feminist thought, approaches the very definition of the role of Black intellectuals: one uniting thought and practice to understand concrete reality (HOOKS, 2014).

This epistemological change in Brazil seems to be closely connected to how our movements have impacted the system of knowledge production in culture and art

and the ways in which such affirmative practices and policies have found ways to (re)organize this knowledge in the most diverse (formal and non-formal) education spaces. Examples of important historical events are the approval of laws no. 10,639/03 and no. 11,645/08, which made studies in Afro-Brazilian, African, and Indigenous history and culture mandatory in all educational institutions in the country; the implementation of the university quota system; various mobilizations both to combat religious intolerance and to legally protect terreiros (where Afro-Brazilian religious ceremonies are performed) and safeguard Afro-Indigenous culture; and, more recently, an editorial boom, certainly an effect of these and many other mobilizations, which also has digital hypervisibility as its driving force.

Participants of a generation which converses, ferments, disseminates, has seen, and sees not only Black authors become (hyper)visible but also a whole knowledge community historically organize itself to fight “epistemicide” by creating their own strategies serving as tools to deal with everyday life, these artistic practices, in addition to expanding the limits of representation policies, have not only historically inscribed racial struggles and their theories in aesthetics but have also expressively been influenced and expanded by them.

It is, thus, this effervescent environment of knowledge production which confirms the importance of this preamble: to refuse, from the outset, any superficial reading which can reduce the use of abstraction in Black poetics as essentially the result of the same motivations that gave rise to Abstractionism in the history of Western art.

As we will see, by abstracting—i.e., isolating or excluding, rather than figuratizing all that, in the light of ultravisibility, can be taken as excess—, these artists present a large reference framework which relies on materiality, ancestry, territories, and the aesthetic and theoretical arsenal of diasporas; elements which ultimately lead us to the central question that gives consistency to the purpose of this text: to question how a museum of contemporary art, such as MAC USP, can be a possible space, from a confrontation with its own collection, to receive, safeguard, and produce knowledge and display contemporary art produced by historically racialized and dissident people.

My tone of action and approximation and the descriptive and virtual voice sustaining the following pages should not confound the reader. They are justified by the fact that this text is the result of my presentation during the seminar held in October 2021 within the framework of this Program. What I will offer in this text, then, are some questions that arise from this contact conforming to the hypothesis of how Brazilian Concretism and Neoconcretism create an equation of value that has, as its consequence, the obliteration (or an attempt at obliteration) of raciality in the ethical and modern aesthetic scene in the country.

If, at first, I propose a reading of some emblematic works of the collection from what Denise Ferreira da Silva’s radical Black thought and feminist poetics have enabled us to reveal, this gesture serves only to base what we are most interested in speculating: how a set of contemporary practices responds, not exactly to them, but what have these works produced as an effect in our present? In practice, this operation is configured by how the feminism of refusal and a whole set of ancestral knowledge have intellectuality nourished Black artists, providing them tools capable of fostering escape routes to this same historicity. The consequences for these poetics, as we shall see, materialize in a refusal to trigger, quote or (re)create a relationship of interdependence that paralyzed them in a movement essentially against history, making room for a performance of the here-now.

On the other hand, we know that it is impossible to avoid the ontological reproducibility sustained by the visualities that define the linearity of this history, and that, even in refusal, it would be impossible to escape the totalitarian effect of Abstractionism, even if none of these artists are declared its descendants. In this case, it would be at least fallible to try to circumscribe, in rigid arguments, the impact of the iconographic encyclopedia of Western art on our imaginary and cognitive formation, as well as the multiple references that populate our imaginaries, especially considering those that were academically trained in it.

Therefore, our goal is neither to measure this dimension or to intend to be passive about universalist and comparative readings that have always taken elected great icons as a ruler to measure the world.

What seems then to be the central reason racialized contemporary artists go toward abstract expression (and, therefore, the escape from the theme-figure norm) is understanding that figurativeness, its critical tools, and poetic procedures have been unable to dismantle the representation of the world counter-attacked by their denunciations. In other words, the utilitarian dimension of language, in exposing violence as a tool of protest, has been unable to decolonize or end the world as we know it, i.e., one in which racial violence makes sense. Thus, abstraction as an expressive strategy has much more to do with the crisis of current representation policies and with an exercise of cognitive liberation than with a return to a historical trend. The escape is, then, as Denise Ferreira da Silva repeatedly points out, “refigured in a critical and creative doing always in reference to a way of existing as a condition of the world, and not as the condition of being in the world, thus producing what is at the same time a feat, an action, a burden, and an artifact” (FERREIRA DA SILVA, 2019).

It is this condition of the world that sustains the production of value in Concretism and Neoconcretism, ultimately building an image of concrete and neoconcrete artists, in a sphere of global art, which is synonymous with art in Brazil and, therefore, the aesthetic reference that imprisons the future that we now intend to excavate.

III

I resume what Ferreira da Silva calls an effort toward an exercise of destruction in an attempt to use black light, an analytical tool by which it would be possible to “shine what should remain overshadowed to keep intact the fantasy of freedom and equality” (FERREIRA DA SILVA, 2019, p. 125). According to the philosopher, as black light focuses on what theory ignores, it breaks it, exposing total violence, thus breaking the code and its consequent equations of value.

Detecting and breaking the code of value production in modern Abstractionism is arduous work, of which I present the first steps since what caught my attention in the collection—and curatorship has long nuanced—is how abstraction is a decisive canon for modern twentieth century Brazilian art; and how, in the twenty-first century, compositional procedures of historically racialized and dissident abstract artists have been performed from materialities, languages, and techniques carrying their own specificities.

Thus, I will explore two works. In this section, I will focus on Max Bill’s Tripartite Unity, made in 1948-1949, and Sophie Taeuber- Arp’s Triangles pointe sur pointe, rectangle, carrès, barres from 1931, part of a work set, together with other names, which I visited, consisting of the fundamental pieces in the Museum collection.

To begin our analysis, I present this image that greatly impresses me for its violent subtlety. It is a photograph called Montagem e limpeza da sala com obras de Sophie Taeuber-Arp (Fig. 1), authored by the German Peter Scheier, which—as the title states—features Taeuber-Arp, an artist who joined the Swiss delegation of the 1st Biennial of São Paulo in 1951, and the Swiss Max Bill’s work.

Legenda

Legenda Peter Scheier. Men Cleaning the Swiss Exhibition – Works by Sophie H. Taeuber-Arp. From left to right: Escalation (1934), Museum of Modern Art – São Paulo – SP, 1951. Peter Scheier/ Instituto Moreira Salles

As a contextualization, Peter Scheier was one of the photographers who dedicated himself to recording art spaces in the 1940s and 1950s. As “a holder of modernist aesthetic references” (COSTA, 2015, p. 100), our goal in reading this photograph is to look at it as a document capable of bringing us information about the art spaces of the time and understand how these representations, from the racial point of view, ended up carrying marks of trade of contemporaneous commissioned images.

The issue of the media dissemination of these images is important for us since, according to many of the exchanges I had during the seminar with professor-researchers Ana Magalhães, Helouise Costa, and Alecsandra Matias, these images end up highlighting how Concretism was, in fact, a political project and how it was staged in the press largely to position São Paulo as a modern capital. Including “Introduction. Abstract Art in Brazil: New Perspectives” by Ana Magalhães and Adele Nelson and “Espaços da arte: fotografia e representação em Peter Scheier” by Helouise Costa, which are rich in showing how communication conglomerate consolidation is structured at the same time as the creation of the first museums, galleries, and collections, such as the creation of MASP itself and of the São Paulo Biennial. Scheier was an employee at MASP and the magazine O Cruzeiro—ventures led by Assis Chateaubriand, a Brazilian twentieth century media magnate.

Since it is not our goal to dissect this information in such a detailed way, but to know what happens when we racialize this photograph, we can only share the following question: what does the presence of Black workers choreographically cleaning the floor from which walls emerge with Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s works mean in Scheier’s image?

If, according to Heloisa Espada (2021), the photographer, in a recurring and stylistic way, used polarities to cause surprise and humor or to mobilize popular curiosity, the presence of Black workers, assemblers, and professionals cleaning the exhibition (as—let us not forget—its title points out) creates a sensationalist opposition through which the bizarre, the grotesque, the unusual, and the picturesque expressed in the racialized Black body that takes its place as the labor of a modern project while Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s works, as the aforementioned and visited Triangles pointe sur pointe, rectangle, carrès, barres, from 1931, rules the space absolute.

What this image helps us to highlight is what the work itself forcefully excludes: how it articulates and abstracts the racial structures of its aesthetic formalist purity through its rationalism and universalism.

This is what we have seen in the description of Taeuber-Arp’s work (Fig. 2), a prominent woman of the Swiss delegation. According to Heloísa Espada:

Taeuber-Arp worked with anonymous-looking shapes drawn with precision instruments (ruler and compass, for example) and their canvases were constructed with few elements which were repeated in varying dimensions. The clarity, sharpness, precision, and uniformity of the surface and the idea of anonymity justify its alignment with concrete art. However, the balance of the painting is solved on a case-by-case basis, not from a pre-fixed rule but from the relations between the elements, filled and empty spaces, proportions, color vibration, and the rhythm created by the repetitions, as observed in Triangles pointe sur pointe, rectangle, carrès, barres. The balance built from differences, sometimes reconciling antagonistic ideas of order and disorder, movement and immobility, symmetry and asymmetry, brightness and opacity, is a central theme in her work (ESPADA, 2021, p. 192).

Legenda

Legenda Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Triangles Opposed by the Vertex, Rectangle, Squares, Bars, 1931. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP)

When we look at this description and invite David Lloyd to the dialogue who, in his book Under Representation (2019) shows that, as aesthetic theory provided the indispensable terms regulating the production and reproduction of the idea of the human subject of modernity, universal and free, Brazilian modern abstraction regulates developmentalism, creating a clear division between the one endowed with Reason and the “Irrational Other,” who, according to the author, will be relegated to studies of disciplines such as anthropology.

On this reductive attribution of a formal purpose to the object in the equation of value of these works, Lloyd states that

[…] This threshold none can pass without a splitting that severs the corporealized human being from the formal subject of aesthetic judgment that is identified with the universal Subject of humanity. Racial figures haunt that threshold, marking the boundary between the subjects of civility and the undeveloped space of savagery and Blackness(LLOYD, 2019, p. 7).

In this 1951 photograph by Scheier, artists Abraham Palatnik, Waldemar Cordeiro, Kazmer Féjer, and Tomás Maldonado pose next to Max Bill’s Tripartite Unity sculpture at the 1st Bienal de São Paulo (Fig. 3). The juxtaposition of photographs is capable, at the very least, of revealing how positions are defined between rotten, dirty, and torn routes of subservient and docile gaze, in high contrast with the aligned suit and the imposing look facing at eye level and with open arms, the object of value to which Bill’s Form, Function, and Beauty came to be revered. According to Ana Magalhães and Adele Nelson (2021, p. 97):

The protagonists of the establishment of a set of institutions of modern art in the post-war period and the emergence of abstraction, were art patrons, artists, and writers, who, with few exceptions, were privileged—literate and mostly white, who even if from different social classes, as well as different ethnic-regional identities—were not subjected to the deprivation or violence of the State. They were, on the contrary, privileged citizens and agents of the image of post-war individuals and society while Brazil experienced an expansion of the urban middle class.

Legenda

Legenda Peter Scheier. Abraham Palatnik, Waldemar Cordeiro, Kazmer Féjer and Tomás Maldonado pose next to Max Bill’s Tripartite Unit sculpture, at the 1st São Paulo Biennial, 1951. Peter Scheier/ Instituto Moreira Salles.

We resorted to mathematics to understand Bill’s principles and operations. He, though rejecting the use of formulas in artistic production, advocated “the use of rational principles in the formulation of themes that could materialize abstractions and artistic propositions” (MARAR, 2004, p. 2).

Although, for Bill, concrete art was the pure expression of the harmony of measure and rule, he “believed in art as a vehicle for the direct transmission of ideas without the danger of their meaning being distorted by any fallacious interpretation. Thus, art spaces become more universal, i.e., a direct and unambivalent expression” (MARAR, 2004, p. 2). Bill (1954) said: “I am convinced it is possible to evolve a new form of art in which the artist’s work could be founded to quite a substantial degree on a mathematical line of approach to its content.”

I find a relation between Bill’s axiomatic and tautological mathematics (Fig. 4), based on Gestalt notions, relativistic theories of matter, n-dimensional mathematics, the problem of the “Moebius” strip—and, thus, geometric demonstrations as a basis for determination and certainty—, in Ferreira da Silva’s explanation, about the use of discipline and its operations. For it is in the assembly and reassembly of this value equation that his analytical tool, the black light, can break these codes (such as the one in the geometric topology of Max Bill’s Tripartite Unity).

I believe that perversity, double violence, and excess of racial violence also result from an ethical character given by the principle of necessity (opposing the principle of life and the principle of freedom). The principle of necessity justifies and explains both mathematical and military operations. A perverse principle since it always justifies itself and mobilizes these possible, acceptable, and necessary violent forces. Therefore, black light goes after this principle, showing it to be one which makes impossible the demand for restoration, for repair. This principle also makes it impossible to see how everything was constituted by industrial capital, which was only possible because of slave labor, 300 years of slave labor.”.

Thus, taking such images (Fig. 4) to exercise historiographical speculation, if we view Black workers in the first photograph as signifiers of an unpayable debt—incurred by the total exploitation of slave labor and the subsequent marginalization, precarious or impossible entry in the labor market—, how do the values impregnated in these works as a symbol of a modern, militarized, and developmentalist São Paulo formally and practically exclude this same Blackness? By abstracting, what is concretely political in these works (not from what it fails to figuratize but from the distance it creates between its ethics and the object to which it represents itself)?

Legenda

Legenda Max Bill. Tripartite Unit, 1948-1949. ©Bill, Max/AUTVIS, Brazil, 2022.

On the attention of the international market to the concrete, the formation of its generative force and its political-economic vocations that influenced, even with its disputes, a whole generation of artists, Magellan and Nelson (2021, p. 97) leave us a clue. According to the authors: […] In fact, the promotion of Neo-Concretism and Brazilian Concrete art at large can be traced back to the late 1950s, when Brazilian diplomatic organisms supported a seriesof exhibitions promoting these artists in the international context, hand in hand with the presentation of Brasília as the new capital city of the country. We could open a long chapter to show how ideas of progress were racialized by the self-production of the European figure in which the transparent “I” becomes a product and instrument of universal reason to oppose a Brazil condemned to tropical miscegenation supporting the myth of racial democracy. The extensive description we have made about geometric formalism serves this condition:

Miscegenation securely inscribes a double historical movement, namely the teleological trajectory—the movement toward transparency—of the white/European subject of a patriarchal “modern civilization” and the eschatological trajectory of his “others;” but, more importantly, it also institutes a precarious social subject, the mixed race one—the Brazilian more or less Black or white—whose destiny is to realize a desire for self-payment (FERREIRA DA SILVA, 2006, p. 74).

As agents of a whitening policy, these foreign artists, together with a group of massively white Brazilian artists who reenacted the European avant-garde, became the aesthetic institutions to be pursued, obliterating, with their precise forms and calculations, any artistic approach, in post-war Brazil, that was not focused on geometric principles or the result of a visual unfolding stemming from their lineages. This explains the formation of a highly reproducible canon in the entire second half of the twentieth century and the consequent hypervisibility, as a propaganda phenomenon, are justified, making abstraction occupy a prominent space in the Euro-American narratives of Latin American art.

In 2018, the artist and researcher Rosana Paulino, one of the organizers of this seminar, elaborated this criticism of Brazilian Concretism in the series Brazilian-Style Geometry (2018) and Brazilian-Style Geometry Arrives in Tropical Paradise (2018-2020). Making a direct quotation of post-war geometric violence by covering the eyes of the Black and Indigenous people represented in her works, Paulino exposes how these causality and efficiency principles serve such procedures of obliteration of raciality as a legal, economic, and symbolic component of modernity. Together with Renata Felinto, in a text published in Zum magazine, titled “Violenta Geometria,” Paulino states:

Geometry is precisely the compositional element that makes it impossible for people to see—and receive our gaze back, recognizing them as subjects. Geometry excludes and forces them to see the world, themselves, and their loved ones from a unilateral historical perspective, from a unique way of being and existing (PAULINO/FELINTO, 2021).

Finally, more than a detailed historical uprising of these two works (which would be impossible here), I focused on raising questions that will continue to be developed about what these and other emblematic works of abstraction history and their hybrids exclude, and what (in terms of a racial obliteration/subjugation and a whitening policy) Scheir’s own photography, unlike the work in his synthesis, denounces.

The choreographed gesture in the image draws our attention. Such movement makes me evoke the kind of memory that this choreography staged in photography, this kind of dance with embarrassed smiles and its back to History, has performed in the present. By imposing the camera as an equipment that captures, shoots, and intimidates, what does this position of “docilely” looking at the ground while cleaning generated nowadays as political mobilization toward the history of this art? And what did turning our backs to a founding moment in the history of Brazilian modern art bring us as a revolutionary force which takes Black depth as negativity (refusal) and fugitiveness (rebellion)?

Let us imagine that we will see these scenes and movements next which photography would neither predict nor tell.

The birth of form: oceanic, porous, and monstrous

As already discussed, my choice of works, when approaching the MAC USP collection, is justified by my interest in continuing research that brings the following question: how, especially in the twenty-first century, compositional procedures of historically racialized and dissident artists who flirt with the abstract have been performed by different materialities, languages, and techniques?

As we have introduced, these artists’ use of abstraction is justified for multiple reasons: due to the critical need to create escape strategies in view of the ultravisibility and fetishization of the theme-figure norm for Black bodies in the art system; the subsequent processes of capturing such representations by a neoliberal techno-normative device, generating a certain emptying of political discourses; and by a need for expression toward a cognitive liberation that, as such, also has, as one of its principles, the production of a space outside encyclopedic norms, both of an Euro-American historiography of art and of a symbolic, violent, and stereotyped imaginary which, as an effect, eventually enclosed what is or should be art produced by Black people. Complexing the Black representational space and the “presumption that Black artists and their works are transparent to social identity” (ENGLISH, 2007, p. 13), these artists refuse the abstract condition that has become “Black art” itself in view of the success that has marked artistic institutions.

In addition to the already fundamental contributions cited and promoted by the circulation of Denise Ferreira da Silva’s thought in Brazil, we must also mention artist and thinker Jota Mombaça’s visual and textual poetics. Claiming the right to opacity, it is important to point out that it was through the generative effect caused by its fire that a vocabulary was forged, a negotiation procedure and a discursive body capable of broadening important reflections on the value production of anticolonial perspectives in the art system and the effects of its modification. According to her, in “Cognitive Plantation,”

[…] Since the commodification of this perspective—our perspectives—depend directly on a certain continuity between our artistic production and our social-historical place, maybe it makes sense to state that the selling of our music, texts, ideas and images reenacts, as a historical tendency, the regimes of acquisition of Black bodies that established the predicament of Blackness at the core of the world as we know it (MOMBAÇA, 2020, p. 6).

Thoughts that offer feedback and inform scenes, speculative fictions, academic studies, performances, videos, music, remixes, and installations outlining her trajectory as an artist who has been summoning the apocalypse and the end of the world as we know it as the only reasonable political measure “which liberates the coming world from the traps of the ending world” (MOMBAÇA, 2016, p. 16). Work that, until now, refuses to settle for dominating space and disrupts itself by its evocation power. Thus, issues involving risk, ephemerality, and the overvisibility of her work with performance have gained critical contours and, engendering in their own language, continue to produce a historical awareness about the fact that trans, non-binary, bixa, and transvestite Black existence is already violent enough to be reiterated as an object of fetishist value, as formally understood in art history ( LIMA, 2020, p. 55).

Due to such practices and their plasticities, these thoughts guided the curatorial party of the Valongo International Image Festival 2018, titled Não me aguarde na retina, developed further in its 2019 edition, in O melhor da viagem é a demora, and, from the 3rd Frestas – Triennal arts of SESC – O rio é uma serpente, of which I was co-curator between 2020 and 2022. Many of the works I will present or the artists I have followed, date back to the commission and residency programs developed over the years.

Inthe same period, I wrote O nascimento da forma: oceânicas, porosas e monstruosas, atext that had direct resonance with the following proposition by Ferreira da Silva, who asks: What is at stake here? What will we need to give up unleashing the radical creative capacity of imagination and get what is necessary for the task of thinking The World differently? Nothing less than a radical change in the way we approach matter and form (FERREIRA DA SILVA, 2016; 2007).

This text then unfolded into two others: a short essay published in the American magazine The Brooklyn Rail, titled “Oceanic, Porous and Monstrous Thoughts”, an invitation that came from the editor of the edition, the artist and choreographer Ralph Lemon; and a second version, which was published as “O nascimento da forma: a personagem da escritora de uma história que fala”, in the Jacarandá journal. At Marcelo Campos’ invitation, this was a special edition developed in collaboration with the Institute of Arts of UERJ

From this intimacy these artists’ research and creation, “O nascimento da forma”, in its different versions became the title-testimony that I found to gather and narrate, in an introductory way, the experiences and learnings with these processes of curatorship—and to address an issue which has become unavoidable: my desire to write a history which takes place in and through language. I make these observations because I try to extrapolate, in these texts, the descriptive tone though which historical narratives take shape and which, by publishing what was a presentation, would become arid to add (especially due to time) the textual poetic components that have helped and help me in this operation.Then, moving toward some of these works, I start by presenting Juliana dos Santos’s (Fig. 5), in which the denial of representation does not appear as a procedure to annihilate subjectivity; arising in performance toward it through what is available with the eyes of the earth, be pursued.

For, after almost half a century of an art history that reflexively privileges the figurative artist as the only agent capable of making or enabling anti-racist policies, dos Santos, in her research Entre o azul e o que não me deixo/deixam esquecer, suggests to us, as does Darby English (2016, p. 8), that is preferable to understand “the representation-abstraction relation in a way that does not reduce it to a simple choice between political engagement and apathetic retreat.”

Legenda

Legenda Juliana Santos. About Time and its Blues, 2021.

Developing blue monochrome paintings with a pigment extracted from Clitoria Ternatea, the artist expands her properties into space through performances and installations, allowing us a chance to live the sensitive and plastic experience that is blue. Thus, it tensions issues that pass through cognitive freedom and ultravisibility when we consider the representational burden and existential traumas nuancing the experience of being a Black woman. Whether launching into processes of listening and living with families cultivating Clitoria, inviting us to drink the blue through the powerful therapeutic dimension of their tea or organically choreographing their flowers by stamping and watering their petals under cotton paper, the artist opens the question about the effort she mobilizes to make the blue happen regardless of its consequent ephemerality, since it is the exposure to light what produces its possible erasure.

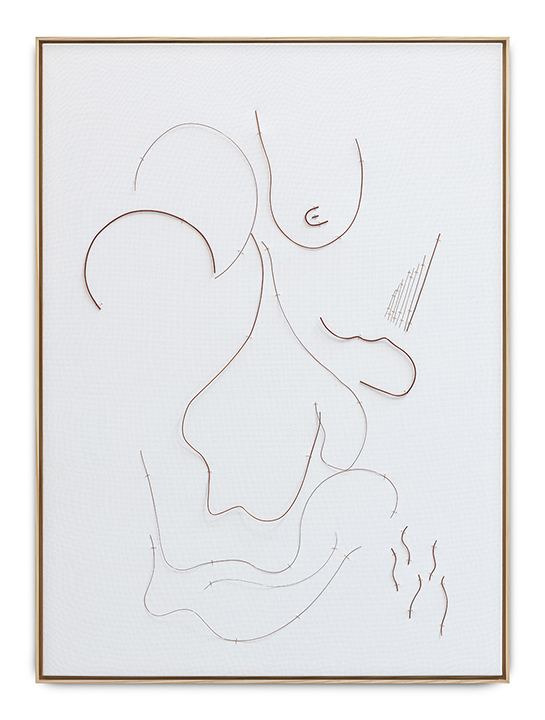

In the series of sculptures and copper on canvas Como colocar ar nas palavras (Fig. 6), the artist Rebeca Carapiá creates a cosmology around the conflicts of language and body norms while staging escape strategies in view of the processes of capture, fetishization, and ultravisibility of identity policies exploited by techno-normative racial capital and its consequent ethical emptying, especially in the last five years, in Brazil. Using feminism of refusal, Carapiá denies colonial categories and markers, resorting to abstraction to create a writing that escapes the compulsory destiny of representation when what is at stake is the intertwining between artistic and resistance practices produced by racialized and dissident bodies such as hers. By seeking other ways of stating difference without explaining it, with regard to materiality performativity, we see that it is in the work with iron and with copper that she deconstructs feminine geographies. By handling ancestrally embedded knowledge and entering the marks of racial-environmental violence of peripheral spaces, Carapiá invites us to a geopolitical debate with the territory of Cidade Baixa, in Salvador, in which she was born and forged.

Legenda

Legenda Rebeca Carapiá. Notebook 3 – from the Series How to Put Air in Words, 2020. Photo: Felipe Berndt.

In the expanded paintings and drawings shown in Buracos, crateras e abraços (dedicada a todos os amigos que não gostam de falar sempre) (Fig. 7), title of Ana Almeida’s individual exhibition held in 2021, the tension between body and space also reappears “to give rise to a mass made of air and color in which everything is rhythm and intensity” (ALMEIDA, 2021). Aiming to renounce the spectacle of representation, the body begins to occupy the space of the crater itself and take place in the abstract space of the holes, in which what is present is the multiple itself in its capacity for contamination and propagation. With Lucia Laguna as one of her main references (according to Tarcísio Almeida, the exhibition curator), the artist uses a series of daily procedures to print gestures and leave traces in the paper, print their proportions, confront the ideas of time in the use of materialities, and produce “rhythmic deformations that saturate colors so that another policy for the body itself is seen” (ALMEIDA, 2021).

Legenda

Legenda Ana Almeida. View of the exhibition Holes, craters and hugs (part 2), 2021. Photo: Ana Pigosso/Courtesy Central.

Added to other practices we could list, we see that these works are performed by an experience of creation centered on the memory of the body as an episteme, on materialities and its performance, and in the dialogue with the space and territory in which these artists forged themselves. What interests us, then, is the ritual, ontological, and performative function of these works enunciated as studies, technologies, tools, and means.

I still see the practice of Iagor Peres in these terms (Fig. 8). He is an artist who attended, in 2019, Residência PlusAfroT. A project which took place at Villa Waldberta in Munich, Germany, of which I was co-curator/creator along with choreographer Mário Lopes. From his dance and performance trajectory, Peres invades spaces with the research Estudos para a minha pele, exploring (organic and non-organic) densities and substances making up spatial relations. Developing his own technique, which he names “Pelematerial,” he navigates between the visible and the invisible, seeking to “understand the role of these invisible layers in what is understood as emptiness, in these spans between us and the world.” According to him, “this thick and amorphous layer that relates to the process of racialization is one of the examples of other existing densities with immeasurable types and variations” (PERES, 2019).

Legenda

Legenda Iagor Peres. Registration of residency process at PLUSAFROT – Villa Waldberta Munich-Germany curated by Diane Lima and Mário Lopes, 2019. Photo: Ana Paula Mathias.

V

A first conclusion can be shared given what we see bloom from this suggestive outcome. As we could see, the absence of the figuratized Black subject as the center of practices we approach does not seems to intend to represent Blackness in its formal-abstract version. The rebellion against any historical evidence takes place in the escape from the theme-figure norm, critical intertextual citation, and abstraction as a metaphor.

But what does this exclusion of the figurative mean for the debate of a visual education which, over time, denounced and fought for the right to representation, mainly through the utilitarian dimension of language?

We believe that it is not a question of creating a polarization with a history of grievances via figuratization which was organized in different historical moments of Afro-Brazilian art. If Du Bois’ instrumental perspective of art as propaganda ended up influencing an entire Afro-diasporic generation by claiming that “Thus all art is propaganda and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purists” (DU BOIS, 1926, p. 324), we see that this group of artists only seems to continue a history of resistance to racial violence which, from time to time, reinvents the processes of exploration and capture, presents itself in the form of a cognitive plantation in the neoliberal institutionalization of the art system:

Coercive strategies have been updated, as we migrated from a system of total captivity to a fractal one where violence strikes us in other manners, thus building some internal asymmetry with regards to the Blackness diagram that allows, on a collective scale, our concurrent death and success (MOMBAÇA, 2020, p. 6).

Moreover, another important conclusion refers to the relation with Time and the dichotomies between History and Ancestry. We see that, though these practices are precisely the reflection of a process of subjectivation and formation within and from a history of Afro-Brazilian art, contemporary critical racial thoughts, and the clues left along the way by artists from other generations, such poetics seem to us to be less interested in formal approximations with history, even if referring to a modern Afro-Brazilian history. With this, we do not claim that names such as Emanuel Araújo, Rubem Valentim or Lucia Laguna are neither revered nor inhabit these artists’ imaginary: what we perceive is that there is a change of procedure and a refusal to maintain the linear and progressive gesture which always subordinates, in art history, the always present future to the past. Therefore, the conclusion we have reached is that these artists honor the past within a temporal dynamic built from understanding time in ancestry and not time in the realm of History.

When Leda Maria Martins claims that “what is repeated in the body and voice, it’s an episteme” (LEDA, 2002, p. 72), her idea of a spiral time becomes central to our conclusions since, with it, we can speculate how the “numerous processes of cognition, assertion, and metamorphosis, both formal and conceptual” (LEDA, 2002, p. 72) constituting the culture of the Black crossroads in the Americas, are transcribed in visuality performability itself. This epistemic crossroads that Martins offers us also enable us to refute any intention, with these readings, to stabilize, impose or pre-determine, from unique characteristics, such practices.

In the contingent risk that historical visual references compose our place of memory, we still have to conjecture the ways in which the memory of knowledge is recreated and transmitted elsewhere, this time via memory environments: oral and bodily repertoires, and gestures and habits, “whose transmission techniques and procedures are means of creating, reproducing, and preserving knowledge.” (LEDA, 2002, p. 72).

From the oralities and “afrographies” that make the epistemic arsenal of these and other artists—to be addressed in the future—, what we want here is to raise the question, full of spatiality, of what kind of discontinuity and fracture could be re-enacted in the timeline of the history narrated by the MAC USP collection.

If, as we have seen, abstraction has already served as a strategy to obliterate the unpayable debt detailing the Brazilian raciality experience, its practice not only disturbs the expectations of historical time but also seems to “release Blackness of the obligation to account for what requires its [own] obliteration” (FERREIRA DA SILVA, 2020). I venture, thus, to say that it awakens us to a vast repertoire exceeding everything that any page or word will ever be able to see and know. For only in presence, in the encounter with you, space, difference, and the other, do your multiple readings open.

References

ALMEIDA, Tarcísio. Corpo chamando espaço. In: Buracos, crateras e abraços (dedicada a todos os amigos que não gostam de falar sempre). Texto curatorial. Rio de Janeiro: Quadra Arte, 2021.

BILL, Max. The Mathematical Approach in Contemporary Art. Arts and Architecture, n. 8, 1954.

COSTA, Helouise. Espaços da arte: fotografia e representação em Peter Scheier. In: Modernismos em diálogo: o papel social da arte e da fotografia a partir da obra de Hans. São Paulo: MAC USP, 2015. Available: https://repositorio.usp.br/item/002762427. Access: feb. 28, 2022.

DU BOIS, William Edward Burghardt. Criteria of Negro Art. Black Thought and Culture: Crisis. v. 32, n. 6, out. 1926.

ENGLISH, Darby. 1971: a Year in the Life of Color. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2016.

ENGLISH, Darby. How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007.

ESPADA, Heloisa. Além da ordem e da razão: a participação suíça na 1a Bienal do Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo. MODOS: Revista de História da Arte, Campinas, SP, v. 5, n. 1, p. 192, 2021. Available: ˂https://periodicos.sbu.unicamp.br/ojs/index.php/mod/article/view/8664232˃. Access: feb. 28, 2022.

ESPADA, Heloisa. Arquivo Peter Scheier: a fotografia como narrativa e vitrine. São Paulo: IMS, 2021.

FERREIRA DA SILVA, Denise. A dívida impagável. São Paulo: Oficina de Imaginação Política e Living Commons, 2019.

FERREIRA DA SILVA, Denise. How. E-flux Journal, n. 105, dez. 2019.

FERREIRA DA SILVA, Denise. Invisible/Obliterating. Pass Journal, 2020. Available: https://passjournal.org/denise-ferreira-da-silva-invisibleobliterating/ Access: feb. 28, 2022.

FERREIRA DA SILVA, Denise. Sobre a diferença sem separabilidade. In: FUNDAÇÃO BIENAL DE SÃO PAULO. 32ª Bienal de São Paulo: Incerteza viva, 7 set – 11 dez 2016. São Paulo: Fundação Bienal, 2016. (catálogo de exposição). Available: https://issuu.com/amilcarpacker/docs/denise_ferreira_da_silva_. Access: feb. 28, 2022.

FERREIRA DA SILVA, Denise. Toward a Global Idea of Justice. Borderline, n. 27, Minneapolis, London: University of Minneapolis Press, 2007.

FERREIRA DA SILVA, Denise. À brasileira: racialidade e a escrita de um desejo destrutivo. Estudos Feministas, v. 14, n. 1, 2006 jan.–abr. 2006, p. 61–83

HOOKS, bell. Intelectuais negras. Estudos feministas, v. 3, n. 2, jul.–dez. 1995, p. 464–478. Available: https://www.geledes.org.br/wp-content/https://estudosdecoloniais.mac.usp.br/uploads/2014/10/16465-50747-1-PB.pdf. Access: feb. 28, 2022.

LIMA, Diane. Por uma educação que interesse aos negros, Revista Zum, jun. 2021. Available: https://revistazum.com.br/radar/educacao-interesse-aos-negros/. Access: feb. 28, 2022.

LIMA, Diane. Fazer sentido para fazer sentir: ressignificações de um corpo negro nas práticas artísticas contemporâneas afro-brasileiras. 2017. Dissertação (Mestrado em Comunicação e Semiótica). São Paulo: PUC SP, 2017.

LIMA, Diane. Em busca do jardim de Laguna. In: CAMPOS, Marcelo (org.). Lucia Laguna. Rio de Janeiro: Cobogó, 2021.

LLOYD, David. Under Representation: The Racial Regime of Aesthetics. Fordham University Press, New York, 2019.

MAGALHÃES, Ana Gonçalves; NELSON, Adele. Apresentação. Arte abstrata no Brasil: novas perspectivas. MODOS: Revista de História da Arte, Campinas, SP, v. 5, n. 1, p. 97, 2021. Available: ˂https://periodicos. sbu.unicamp.br/ojs/index.php/mod/article/view/8664173˃. Access: feb. 28, 2022.

MARAR, Ton. Aspectos topológicos na arte concreta. In: Segunda Bienal de Matemática da Sociedade Brasileira de Matemática, v. 1, p. 2, 2004.

MARTINS, Leda. Performances do Tempo Espiralar. In: RAVETTI, Graciela; ARBEX , Márcia (org.). Performances, Exílios, Fronteiras: Errâncias Territoriais e Textuais. Belo Horizonte: FaLe/UFMG/PosLit, 2002.

MOMBAÇA, Jota. A Plantação Cognitiva. In: MUSEU DE ARTE DE SÃO PAULO ASSIS CHATEAUBRIAND. MASP AfterAll. São Paulo: MASP, 2020. Available: https://masp.org.br/https://estudosdecoloniais.mac.usp.br/uploads/temp/temp-QYyC0FPJZWoJ7Xs8Dgp6.pdf. Access: feb. 28, 2022.

MOMBAÇA, Jota. Rumo a uma redistribuição desobediente de gênero e anticolonial da violência. Cadernos do Grupo de Pesquisa Oficina de Imaginação Política. São Paulo: Incerteza Viva, 2016.

MOMBAÇA, Jota LIMA, Diane. In: LOPES, João Paulo Siqueira; TICOULAT, Fernando (org.). 20 em 2020: Os artistas da próxima década: América Latina São Paulo: Act., 2020.

PAULINO, Rosana; FELINTO, Renata. Violenta geometria. Revista Zum. Fev. 2021. Available: https://revistazum.com.br/revista-zum-19/violenta-geometria/. Access: feb. 28, 2022.

PERES, Iagor. Aqui no limite do vão que estamos. 2019. Ehcho. Available: https://ehcho.org/conteudo/ali-entre-nos-um-invisvel-obliterante. Access: feb. 28, 2022.