This is one of those rare occasions that shouldn’t be so in a country like Brazil. Forty researchers who make up the better part of contemporary intellectual enterprise meet to exchange knowledge and research with artists, curators and other intellectuals from different corners of the Atlantic, a happening that should not be an exception in the daily production of knowledge in Brazil. And this is only possible because we are immersed in the context of a higher education institution that, in very complex ways and not without deep contradictions, takes a stance that has not always been nor is recurrent. The Research Curatorial Practices Project of MAC USP, in partnership with the Getty Foundation from the US, offers this possibility by mobilizing a desire that takes shape in the institution and runs through its current constituent agents. Managements that reflect on their attitude towards the unavoidable mark of Brazilian racialization go far beyond a strategic proposition of the 21st century art system. Bringing in black players to compose the institution’s advisory board and ensuring they have a voice in decision-making spaces is pressing, and its effective realization challenges privileged configurations in the main Brazilian art institutions.

What I present here is the result of the project’s invitation to three racialized curators

from different regions of Brazil—myself included—with the aim of analyzing a collection currently comprising over 10,000 items. From it I must select a sample. But what? The first impulse prompted by the lines of research, which I believe justify the position I occupy herein, would be to search for black authors in the institution’s collection. This was the first observation, which drove my first efforts. However, as a black professor of history of art, I cannot but consider that we are immersed in a history of art and in an art that I have dubbed, along with other colleagues—without forgetting to mention Abdias Nascimento (2016)—as “white Brazilian” (SIMÕES, 2019, 2021; AMÂNCIO, 2021). This art and this history of art point to a set of choices and samples in which white authorship is the chief element of their canons, an overwhelming and definitive presence in its collections and, consequently, in its institutional exhibitions, critical debates and bibliographies.

Giving the black artists of the collection the leading role that they have not always played in the institution’s exhibition venues is urgent and non-negotiable in my proposal. However, I am also interested in exploring the history of works produced by white artists who, capturing black bodies, framed lasting perspectives in Brazilian art, kindling a field of constant dispute. I am interested in procedures that reveal how long these works endure in the displays of the contemporary art museum of the largest university in Latin America, in the largest country on the continent, in the largest destination of the slave trade, with the largest black population outside Africa. Therefore, it is also essential to have access to documents that confirm the trajectories of each of the selected works.

On being called to occupy this place I deal with, which is that of curator, some aspects are hence indispensable. The first is to reinforce the centrality of my notion of the exhibition as film montage (SIMÕES, 2019). I have insisted on the fact that the exhibition holds a key position in the writing of contemporary histories of art that have not necessarily been addressed in our main bibliographic references. In this sense, exhibitions are spaces in which different fragments are interconnected to make up valid narratives for reflection on contemporary paths for the history of art. Although these artistic fragments have their specific forms, their origins, their first meanings, when entering the exhibition space their unique frames move into another possible field of meanings and narratives, and it is therein, in that space of operations, that film montage becomes the conceptual image to reflect on the constitution of narratives that are specific to that circumstantial meeting of fragments.

Considering what happens when these fragments come together in the space as star clusters is, therefore, the basic premise of this selection of works. Shuffling chronologies to create conflict is the path chosen for this working stage. This choice is also a way of relativizing what we have chronologically called modern or contemporary, especially when talking about art produced in Brazil, where these temporal definitions shift and settle continuously. After all, what is contemporary at MAC USP, not to mention in a context in which the city of São Paulo holds a dominant position? Even the definitions of modernism are imprecise, especially because we are talking about a collection formed in the metropolis of São Paulo, which insisted on viewing itself as the standard of an excluding idea of modernism (CARDOSO, 2022).

When I speak of contemporaneity, I wish to understand it from three key points: 1) understanding the mobility of the past and its ways of being narrated; 2) the recognition of sophisticated power strategies associated with the visibility of some narratives to the detriment of others; and 3) the current clash between those narratives.

In this sense, the contemporary exhibition has the potential to be an editing table for histories of art that are committed to the need to reposition their discourses, methodologies, subject matters and theoretical references when faced, for example, with the unavoidable asymmetry that has characterized what we call Brazilian art, when considering race and its necessary intersections.

Settlement as a procedural dimension, or about finding constellations

Here I evoke a choice and a change of direction that resulted from visits to the MAC USP collections and exhibitions, a stage in the process that leads to this article.

In order to exemplify the encounters that I propose regarding a display-oriented approach to the history of art, I could take as an example one of the panels that illustrate Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas (1924-1929).

In this sense, the panel would make it easier to convey what I want to suggest as constellate encounters between different items of the collection that may be placed in a relationship of conflict and consensus in the exhibition space.

However, one must search through all layers of references for those that speak to us more intimately and dialogue more deeply with our desires and commitments to the assumption of racially located epistemologies.

If I want to reflect on these encounters between images that seek to understand how we became settled in this place we call Brazil, the constellation image must also be of a different order.

Therefore, it is not Warburg’s panel that emerges before me, but another constellation, of a different order and that speaks directly to this curatorial proposal. I am referring to the work by Rosana Paulino in the MAC USP collection that guided the choices that follow. Above all, I am interested here in the constellation that I learned to see with Paulino and that lives over the head of the black woman humanized by her in the Assentamento [Settlement] installation (2013). The two engravings by Rosana Paulino in the MAC USP collection were acquired in 2017, therefore very recently. It should be noted that my investigations revealed the almost isolated existence of Rosana Paulino as a black artist in the museum’s collection.

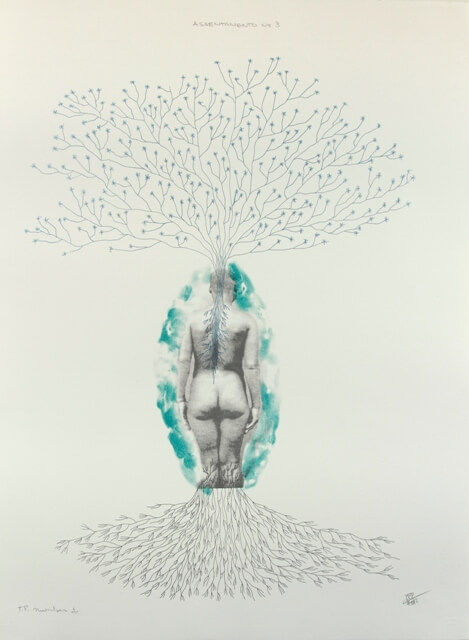

For now, I want to focus on Assentamento nº 3 (2012), one of the engravings. It depicts a black woman viewed from the back. Her legs end in species of roots that, as the title says, settle her into the ground. The woman does not have her back to us by choice. Front, side and back views of black individuals are a typification. These images became recurrent between the 16th and 19th centuries, when the black and indigenous body used to be presented according to the protocols of the pseudoscience of the time, which was conducted by European travelers who came to discover the particularities of the colonized tropics. Pseudoscience that scrutinizes and catalogs existences by removing their subjectivity and, hence, their humanity.

Legenda

Legenda Rosana Paulino. Assentamento nº 3, 2012. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

But I want to talk about the woman’s head, elevated to the status of human by Rosana’s procedures. From her head sprout what, at first sight, seem to be the branches that would complete this kind of ancestral tree—a tree born from the woman’s vertebrae and which is sustained and maintained by her. The artist has stated on numerous occasions that the word settlement here has complex meanings, ranging from the idea settling on the land, like the enslaved blacks who arrived here, to the religious act of settling an offering present in Afro-diasporic religions.

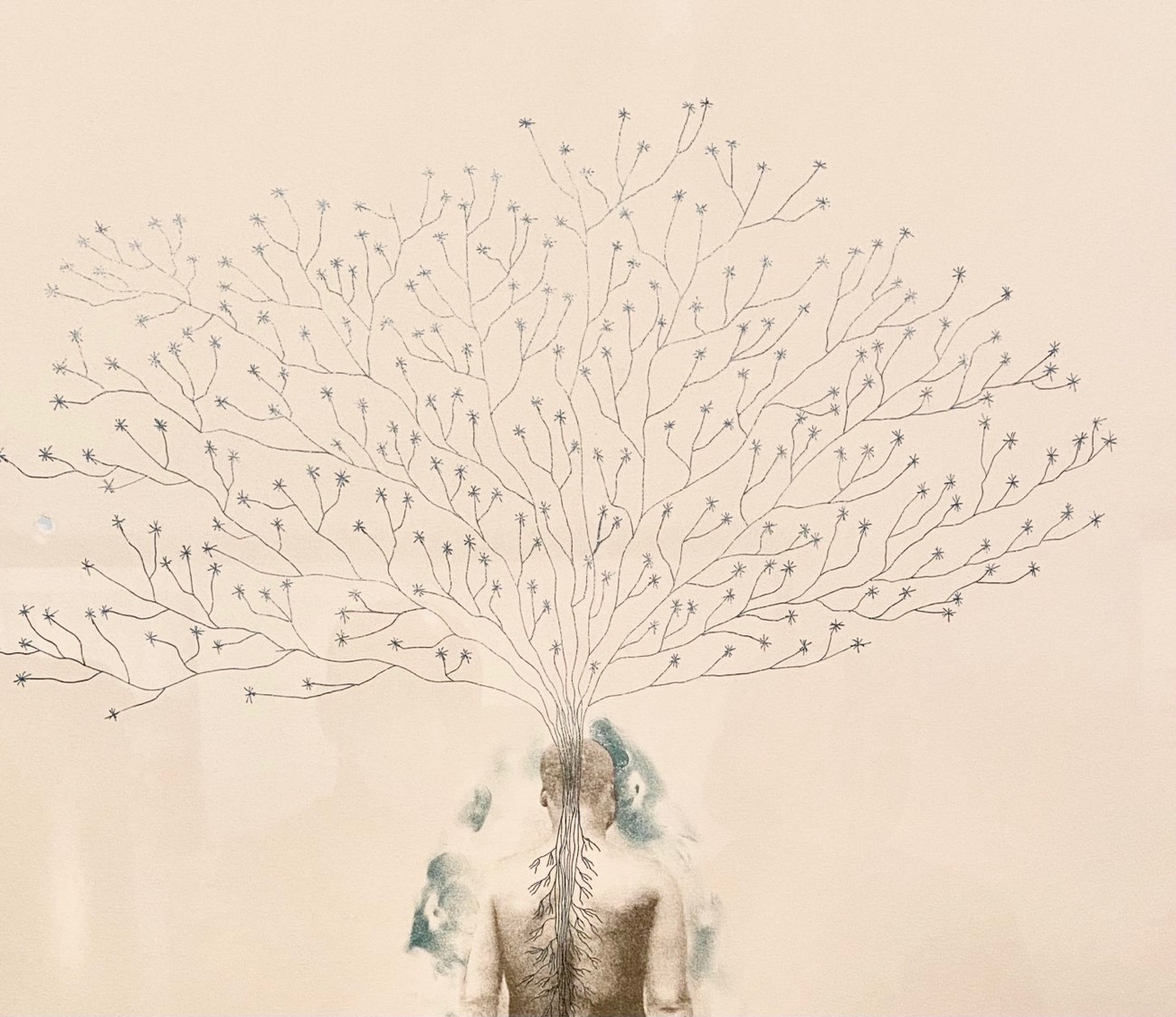

In re-encountering the work in Paulino’s presence at the museum’s display, I was invited by the artist herself to take a closer look. Then came one of those moments in which an image seen so many times presents itself again in its ability to cause continuous wonder. At the extremities of this tree live stars, live constellations. From the roots and stem vertebrae arises a luxuriant profusion of lines that ends in stars that meet and drift apart. They are near and far. They spread over the surface of the paper without having to obey a single shape, a single direction. They form constellations without losing their individual outlines.

Legenda

Legenda Rosana Paulino. Assentamento nº 3, 2012. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

Well then, Aby Warburg was no longer necessary to reflect on the constellate encounters of artworks in the exhibition space and their shared and particular meanings. The constellation, a procedural and methodological image of what I develop here, is definitely present in the humanity of the black woman that appears in Rosana Paulino’s poetic work. After all, we also aim here to settle other epistemologies for art, its systemic gears and institutions, its possibilities for writing a history of art that addresses contemporaneity. One must therefore settle this discipline on foundations that guarantee existence, continuity, the view of the present and the rewriting of the past.

Thus, Assentamento nº 3 is no longer just one of the images that I intend to display but becomes also a point of reference for the very idea of encounters that start out from a common core and spread out in countless possibilities of meaning, shuffling chronologies and procedures to insist on the settlement of a history of art that self-problematizes based on the MAC USP displays.

In presenting the works that I selected in this curatorship, I also try, as far as possible, to inform the number of times they have been exhibited, which was also part of my inquiries and made possible thanks to information obtained from the museum’s department of documentation, archive and reserve collections. Thus, I was able to address at the same time the reserve collections and the exhibitions. What was displayed? What was relegated to the reserve? What was chosen to be exhibited more often? What was more or less seen? What fragments entered the stories built inside the museum’s exhibits? I also indicate the racial marker of the selected artists, which should be visible in the signs of a possible establishment of this proposal in the exhibition space.

Legenda

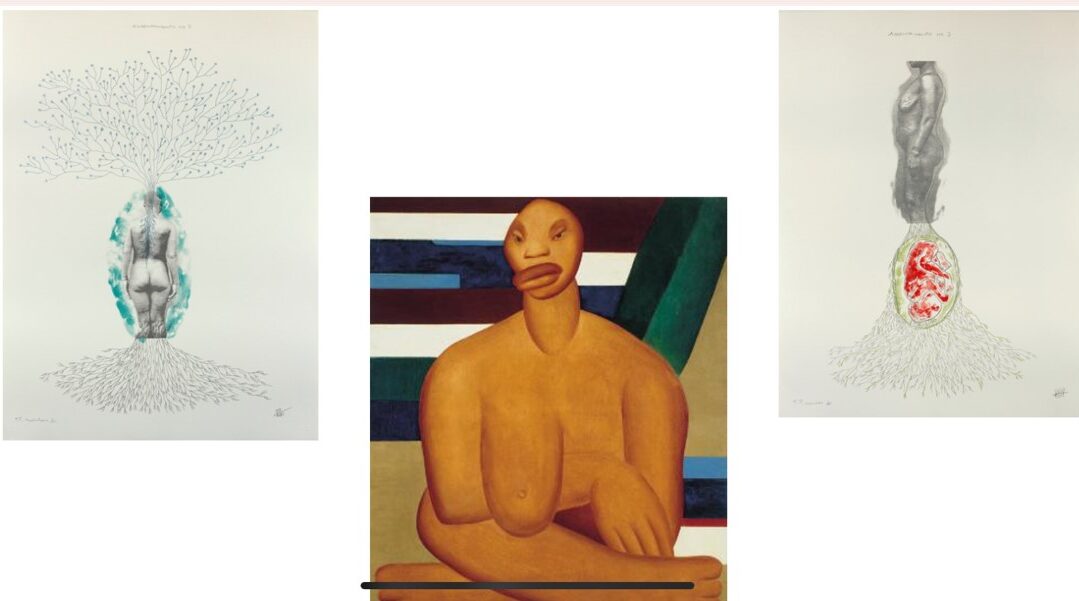

Legenda [constellation]

Tarsila do Amaral. A Negra [The Black Woman], 1923. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

Rosana Paulino, Assentamento nº 2, 2012. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

Rosana Paulino, Assentamento nº 3, 2012. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

Settlements and conflicts of the black woman’s body

Settlement is, then, the starting point that summons to these unforeseen meetings. Between the two engravings is one of the most controversial works by the São Paulo modernist artist Tarsila do Amaral.

Something happens when we bring together two poetic gestures by two Brazilian women artists who inhabit different worlds in every sense. Even when addressing modernist canons that have long been codified in the national iconosphere, as is the case of Tarsila do Amaral’s A negra [The Black Woman] (1923), there is room for creation when it is juxtaposed to the black woman’s body on which is settled the history of a country and the entire invention of modernity that imposes itself in Rosana Paulino’s work. Juxtaposing it here to the black woman, viewed through the eyes of a white artist from the São Paulo elite, celebrated as a fundamental name of an artificially national modernism, does not imply highlighting a supposed essence that might inhabit both artists and result in visuality. Before that, it is worth exploring the gaps that bring together and push apart the years of 1923 and 2012, modern and contemporary art and the views on bodies of black women in Brazil. There is also the shift in possible authorships in the circle of acknowledgment of the artistic system and its interdictions and accesses in the times and existences of one and the other.

Undoubtedly, what is also at stake here is the representation of blacks from modernity to contemporaneity. I draw attention to the invention of the modern black in white Brazilian art a few decades after the abolition of slavery. This figure represented, on a large scale, the reenactment of primitive ideas that inhabited European modernist points of reference and that here replace Africa or Tahiti with urban hillsides and remnants of slave quarters. I agree with Rafael Cardoso when he states that, regardless of the intentions of each artist, the procedure of configuring subordinates through folklorization and/or parody resulted in perpetuating stereotypes (CARDOSO, 2022, p. 26).

At the same time, contemporary relationships expose the conceptual turnaround effected by the production of black Brazilian women artists, who have proposed not only different imagery repertoires, but, above all, reinterpretations of the very idea of country.

Another element of analysis is the frequency with which Tarsila’s work has been exhibited and referenced in publications. According to data from the MAC USP documentation department, between 1961 and 2020, Tarsila’s work was exhibited 73 times in displays in Brazilian and foreign museums and appears, according to data provided by the museum, in more than 75 publications.

It is, therefore, a matter of addressing the frequency with which canonical works by white São Paulo artists, from elitist social spaces, are enforced on the public’s eye and mind by an organized institutional structure that keeps them in a state of constant visibility. Naturally, one should consider that it is also a work that does not happen alone, but which at once impacts and is impacted by a set of truths entrenched in history, criticism and theory about the centrality of São Paulo modernism and of the artist as one of its main icons, which also makes her a “desired presence.” I understand that such a desire does not exist outside the space of culture; it is engendered also by its works and, before that, in the selections that present some to the detriment of others.

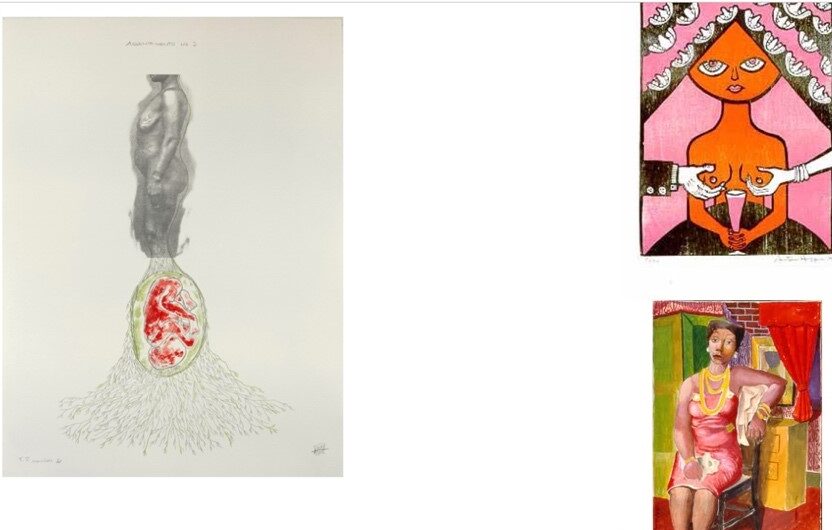

We can add to this constellation another artistic fragment: the woodcut by Antonio Henrique Amaral, a white artist, entitled Madonna (1967), from the O meu e o seu [Mine and Yours] album. In the woodcut, a black woman seen from the front has her breasts touched by two white hands apparently belonging to man and a woman, while the black Madonna bears in her hand a kind of goblet.

Legenda

Legenda [constellation]

Antonio Henrique Amaral. Black Madonna, 1967. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

Emiliano Di Cavalcanti. Untitled (Sitting Woman), 1941. Museum of Contemporary Art, University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

Obviously, I understand the origins and particular creative projects of these artists; however, I am thinking of the unforeseeable that happens when different fragments meet in the exhibition space. In this sense, one must understand that the artist’s world of intentions and particular contexts is one of the various dimensions of the life of a work, understanding that it is long-living and also reverberates according to how it is displayed. The work was exhibited only once, in the exhibit O papel da arte: obras em papel na coleção MAC USP [The Role of Paper in Art: Works on Paper in the MAC USP Collection] (2000–2001), and referenced in the publication of the same title.

There is also place in this approach for a work by Di Cavalcanti, an emblematic figure in the belligerent relationship between racialization and modernity, one of his many images of black women called mulatas. This is a precious item dating from 1941 entitled Mulher sentada [Seated Woman], in gouache and graphite on paper, exhibited eighteen times at MAC USP and other institutions between 1985 and 2018.

Rosana’s forceful work is, here, the element that causes friction with the representations of white modernist artists and the bad habits of encapsulating black bodies within pre-established canons and situations. The display becomes the editing table that enables those readings.

Legenda

Legenda [constellation]

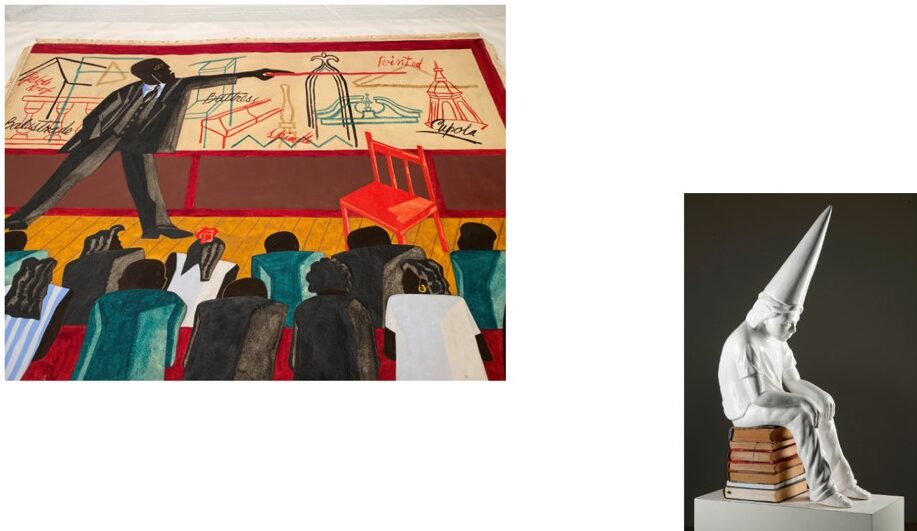

Jacob Lawrence. The Class, 1946. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP). © Lawrence, Jacob/AUTVIS.

Flávio Cerqueira. As They Taught Me, 2011. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP). Photography: Rômulo Fialdini.

Lecture on Architecture, from 1946, by the black American artist Jacob Lawrence, is a work of prominence in the MAC USP collection. However, documents on the painting reveal that since its purchase, in September 1949, it has been displayed only five times—four of them still at MAM, before the foundation of MAC USP—and only once between 2012 and 2013, in an exhibition entitled Crítica de arte moderna no Brasil [Criticism of Modern Art in Brazil], which seems to have resulted from an academic research experience.

Choosing to exhibit it also means forcing the entry of other images and references to contribute to the discourses raised by the museum on modern and contemporary, and reinforcing the subject of black authorship, which does not appear recurrently in the institution’s exhibitions or displays over time.

Here, Lawrence’s work appears juxtaposed to another notion woven by the space of education and its singularities. It is the work of the contemporary black artist Flávio Cerqueira, Foi Assim que me Ensinaram, from 2011, which entered the collection in 2014, donated by the artist. It was exhibited from 2013 to 2020 in the museum’s permanent exhibition.

The subject matter of education and its implications appears here as a way of provoking the idea of temporal continuity in the production of black artists of the diaspora. Lecture on Architecture, comprising a black professor lecturing to a class of black students, in Lawrence’s work, and its meeting with the boy in the dunce hat, in Cerqueira’s work, is just a strategy to show the continuous production of black artists in different Afro-diasporic contexts.

Emblems, Exus and Candomblés

Regarding the relationship between Afro-Brazilian art and religiosity, there is a simultaneous reference to the most recurrent conception of this art and, at the same time, to a kind of continuous association made by specialized critics that has, for many years, shackled black production solely to that notion. Indeed, it is no exaggeration to claim that from classic texts, such as the one written by Nina Rodrigues in 1904, in Kosmos magazine, through the writings of Mariano Carneiro da Cunha to the definitive contribution by Kabengele Munanga with his Arte afro-brasileira: o que é afinal? [Afro- Brazilian Art: What Is It After All?] (2015), religiosity is understood almost as synonymous with Afro-Brazilianness. Although most of these definitions refer to a search for possible origins, it is not uncommon for religiosity to become an almost mandatory category for most specialized critics when analyzing the production of black artists, even if the works do not relate to or diverge from that theme.

In Rubem Valentim’s work, the symbols of black Brazilian religiosity impose themselves as indispensable elements in the formulation of modern to contemporary in local art. The black artist is strongly associated with the recurring link between Afro-Brazilian art and religiosity, but that is not his sole approach. From his works emerge spaces of motion that accumulate the Afro-Atlantic experience and an imposing testimony of modernity necessarily conceived from that perspective

Legenda

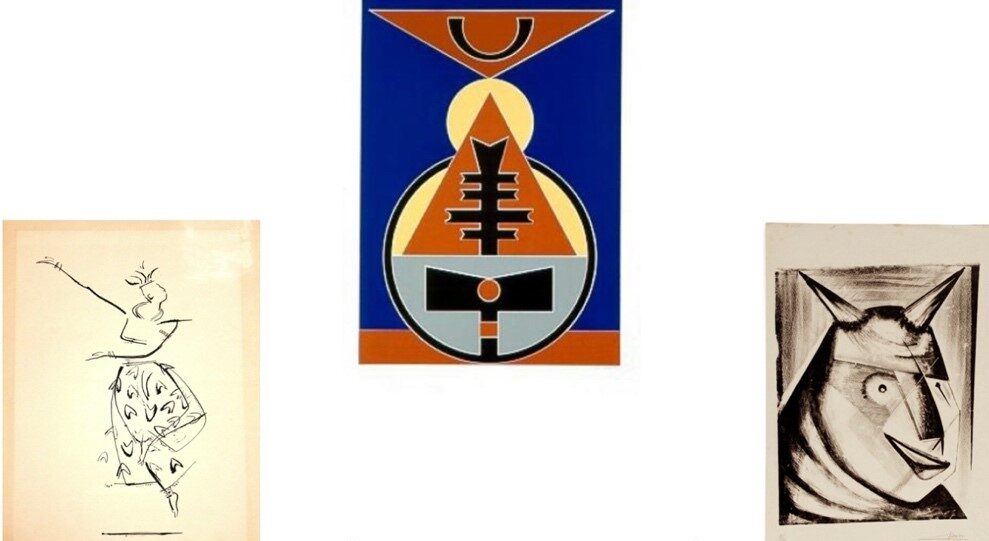

Legenda [constellation]

Carybé. Figure of Candomblé, 1956. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

Rubem Valentim. Emblema IV, 1989. Museum of Contemporary Art, University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

Mario Cravo Júnior. Exu, 1952. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

Rubem Valentim appears here with his Emblema IV, from 1989, exhibited twice in Brazil, in 1991 and 2007, and part of a considerable number of his works in the museum’s collection.

However, religiosity also appears in a shifting manner in works by white artists, usually associated with a foreign view of the inherent processes of those religions. A good example is the lithograph by Mario Cravo Jr., in which the figure of an alleged Eshu is represented with traits varying between beastlike and childish.

What if to this constellation were also added Figura de Candomblé, from 1956, by the Argentinian white artist who dominated much of the popular imagination of what was understood for decades as Afro-Brazilian, the painter Carybé? What if the display tacitly made it possible to compare these works by black and white artists? Far from providing definitive answers, the friction between these different productions may be a way to open up other spaces for their interpretation. There is also in this friction a play that involves the association of Afro-Brazilian art with a kind of intrinsic content, through which religiosity paved the way for this field to be surrounded by black content rather than black authorship, as has been assumed in the late 20th century and early 21st century.

Legenda

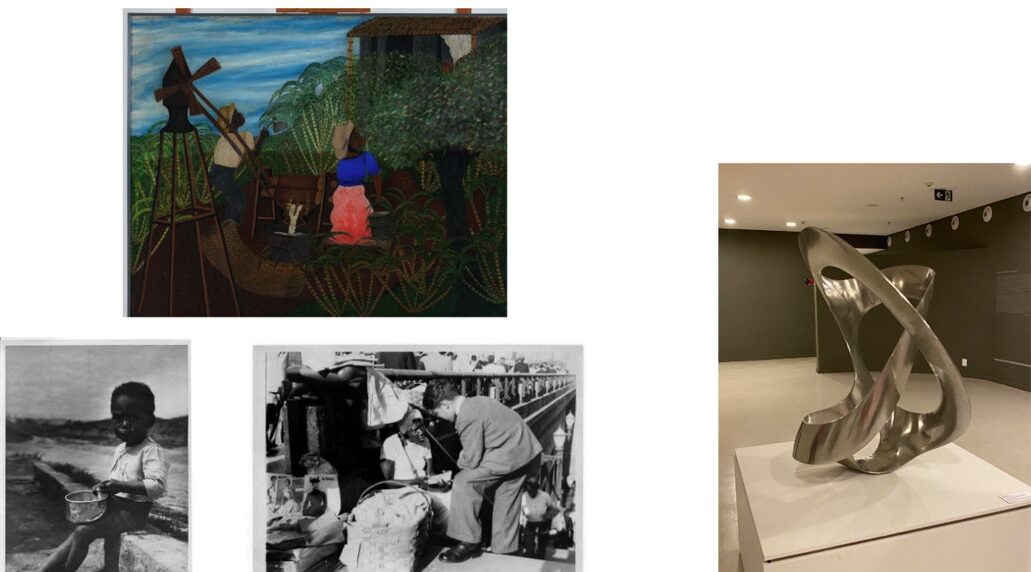

Legenda [constellation]

Heitor dos Prazeres. Moenda, 1951. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

Alice Brill. Sumaré, from the Series Flagrantes de São Paulo, 1954. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP). Alice Brill / Instituto Moreira Salles.

Alice Brill. Viaduto do Chá, from the Series Flagrantes de São Paulo, 1954. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP). Alice Brill / Instituto Moreira Salles.

Max Bill. Tripartite Unit, 1948-1949. ©Bill, Max/AUTVIS, Brazil, 2022.

Asymmetric mills and modernities

In one corner of the room is Max Bill’s Unidade tripartida (1948-1949). It is there as one of the ultimate works of a desire for modernity in Brazil that expands from it to fit into complex processes of invention of a society that intends to hide the asymmetries of its constitution. Projects exhibited at the 1951 São Paulo Biennale are gathered as a space of assertion of new economic and geopolitical expectations. Not at the edges, but at the epicenter of this debate, other modernities overlap. In the constellation, a Biennial and a notion of modern art marked by a number of hierarchies running through race and class. Moenda, from 1951, the key work in the production of the black artist Heitor dos Prazeres, awarded at the same first São Paulo Biennale, thrusts us into a plot ranging from artistic categories to places of the black population in so-called Brazilian modernity. Once again, through the eyes of another foreigner, part of urban life is included with Alice Brill’s Flagrantes de São Paulo photo series (1954). One must also consider the possibility of inserting documents such as the records of the Afonso Arinos law, which was also supposedly proposed in 1951. Modernities that insist and endure in the time we call contemporary.

Geometrizations, constructions and black authorships

I think of a work that is not in the collection. I think of the conceptual image that can emerge from the Geometria à brasileira chega ao paraíso tropical [Brazilian-style Geometry Arrives in the Tropical Paradise] series (2017-2018), also by Rosana Paulino. On Rosana’s surface, geometric elements refer to the artificial tradition of geometry as an emblem of a modern Brazil in dialogue with international trends in art, clashing with images that call out incessantly for their impossibility of framing the language that is imposed.

Legenda

Legenda Rosana Paulino, Brazilian-style geometry arrives in the tropical paradise, 2017-2018.

The constructive and geometric heritage is ubiquitous in the MAC USP collection. Let’s not forget that it houses Max Bill’s Unidade tripartida. Even recognizing this trend as a canon in 20th century art, it is possible to approach it from the viewpoint of a long arc of time dominated by works by black artists. With different senses and uses in fields of meaning that come close and drift apart, we have the works that juxtapose the Shango deity of the work Untitled (1968) by Valentim, between two- and three-dimensional (it appears regularly in the museum’s exhibitions between 1986 and 1986, making a comeback in exhibitions in 2002, 2007 and 2010), in proximity with Emanoel Araújo’s O quadrado, o círculo e o disco fragmentado [The Square, the Circle and the Fragmented Disk], from 1994 (on permanent exhibition since 1988 in the garden of the university campus, on the site of the former MAC USP building), and Estruturas dissipativas/Balanço [Dissipative Structures/Balance], from 2012, by the black artist based in Rio Grande do Sul Rommulo Vieira Conceição. Rommulo Conceição’s work was jointly donated to the collection by the artist and Casa Triângulo gallery in 2013, having been exhibited in that same year and in 2015. These works are grouped to address the survival of constructive elements in contemporary black art.

Legenda

Legenda [constellation]

Rubem Valentim. Untitled, 1968. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

Emanoel Araújo. The Square, the Circle and the Fragmented Disk, 1994. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

Rommulo Vieira Conceição. Dissipative Structures/Balance, 2012. Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP).

Furthermore, together they constantly play with the historical and already outdated view of an Afro-Brazilian art supposedly justified by adhering to a previous set of repertoires intrinsic to the objects and which could be immediately associated with a so-called repertoire of black issues. Such views are simultaneously asserted and imploded in the gathering of these works. A breach is opened to discuss the possibilities of black artists addressing elements that are not necessarily associated with the debate on race, as in the constructive structures of Rommulo Conceição.

A thought-provoking program

This proposal makes no sense if restricted to the physicality of the exhibition. All these actions can only powerfully reverberate if they are inextricably linked to an educational program in which the audience is an agent of the many relationships made possible by the proximity of these works. In this sense, the program should not be viewed as an illustration of the ideas of the exhibition or curatorship, but must necessarily be the inauguration of a continuous sense of distrust of what is being shown.

The proposal presented here is, in its different configurations, is also an educational proposal. It is so because it evokes doubt as the main working material.

It would be extremely important, for example, to have a continuous program aimed at educators inspired by the different questions that are posed here, collective creation laboratories and propositions that constantly cause the audience to distrust what is presented in these encounters.

As I propose it, there is no hierarchy between the elements of debate coming from the field of history and criticism of art and those that fulfill the role of instigating other views that activate the works in different possible ways and that are made possible by educational proposals. At a time when a museum seeks to resize itself in the face of the challenges of a new management, enhancing educational programs may be a means to exercise daily institutional criticism, like that which motivated this so far superficial and specific set of proposals. I end by citing two colleagues that I greatly admire. From Thiago de Paula I reinforce the key idea of the educational program in a museum that is indeed focused on urgent redistribution. From Horrana Santoz, black curator at the São Paulo State Pinacoteca, I offer a summary of the strategy stated in an informal conversation: “This wall is big, I might not be able to pull it down, but I will make it crack in some places.”

References

AMANCIO, Kleber A. de O. A História da Arte branco-brasileira e os limites da humanidade negra. Revista Farol, v. 17, n. 24, inverno 2021, p. 27-38. Available: https://periodicos.ufes.br/farol/article/view/36351. Access: feb. 28, 2022.

CARDOSO, Rafael. Modernidade em preto e branco: arte e imagem, raça e identidade no Brasil, 1890-1945. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2022.

MUNANGA, Kabengele. Arte afro-brasileira: o que é afinal? Rio de Janeiro: Azougue, 2015.

NASCIMENTO, Abdias. O genocídio do negro brasileiro: processo de um racismo mascarado. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 2016.

RODRIGUES, Augusto Nina. As Bellas Artes dos colonos pretos no Brazil: a escultura. Revista Kosmos, ed. 8, 1904. Available: http://memoria.bn.br/docreader/DocReader.aspx?bib=146420&pesq=nina+rodrigues&pagfis=386. Access: feb. 28, 2022.

SIMÕES, Igor M. Montagem fílmica e exposição: vozes negras no cubo branco da arte brasileira. Tese (Doutorado em Artes Visuais), Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2019.

SIMÕES, Igor M. Todo cubo branco tem um quê de Casa Grande: racialização, montagem e histórias da arte brasileira. Revista Philia – Filosofia, Literatura & Arte, v. 3, n. 1 (maio), p. 314-329, 2021. Available: https://seer.ufrgs.br/philia/article/view/113790. Access: feb. 28, 2022.

WARBURG, Aby. Atlas Mnemosyne. Madri: Akal, 2010.