“to this country I brought my orishas over my head all my family tree ancestors, the roots” (LUBI PRATES, 2019, p. 28, our translation)

Contemporaneity is characterized as a time in which we communicate through virtual images mediated by electronic equipment. Using cell phones, laptops, and desktop personal computers we receive and send images of our bodies or, in most cases, of our faces. Connected by these remote communication devices, with no need for any physical traversal, we establish virtual, regular and safe contact with family, friends, teachers, bosses and other people from different parts of the planet, which helps to keep our social relationships alive and feed our humanity.

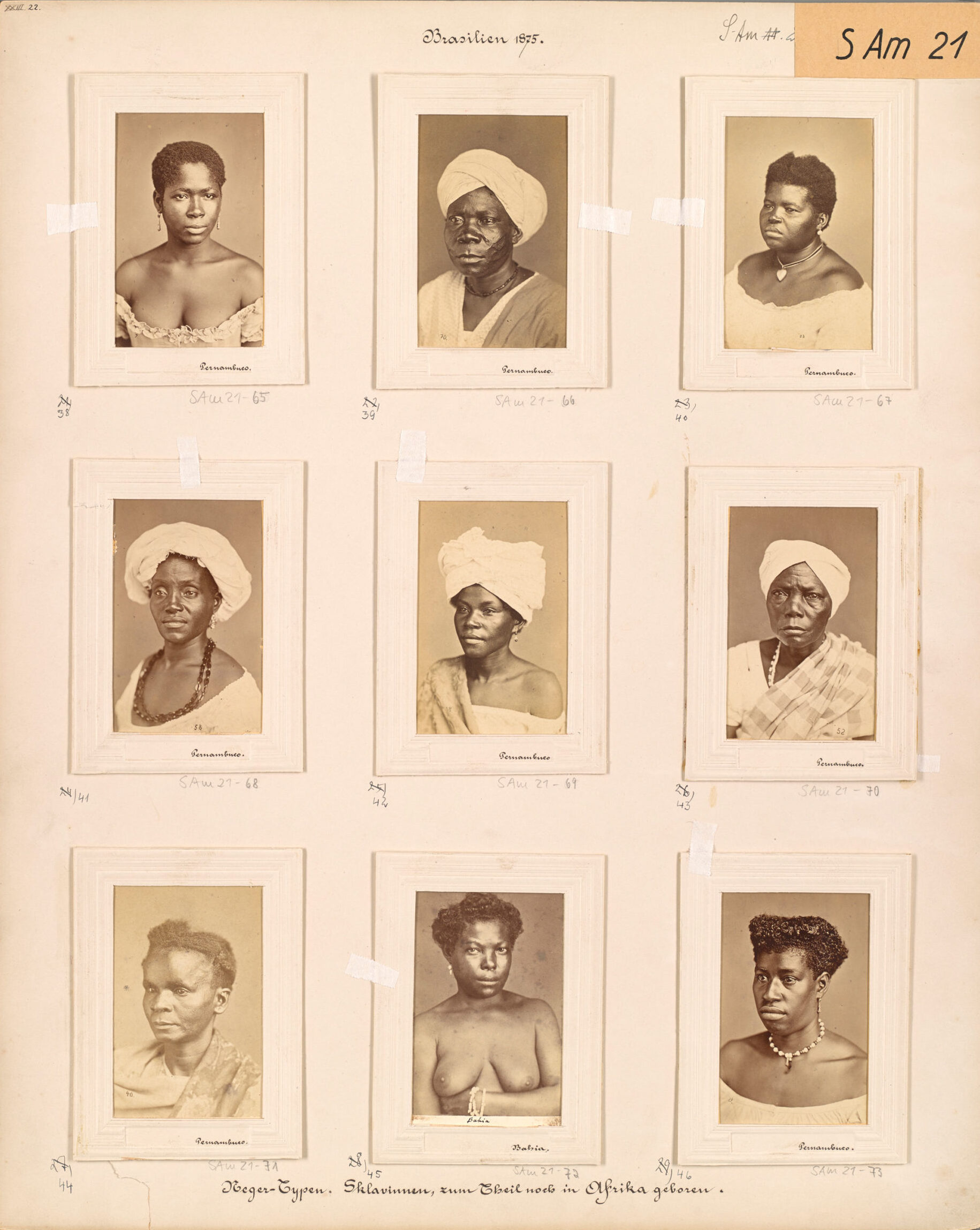

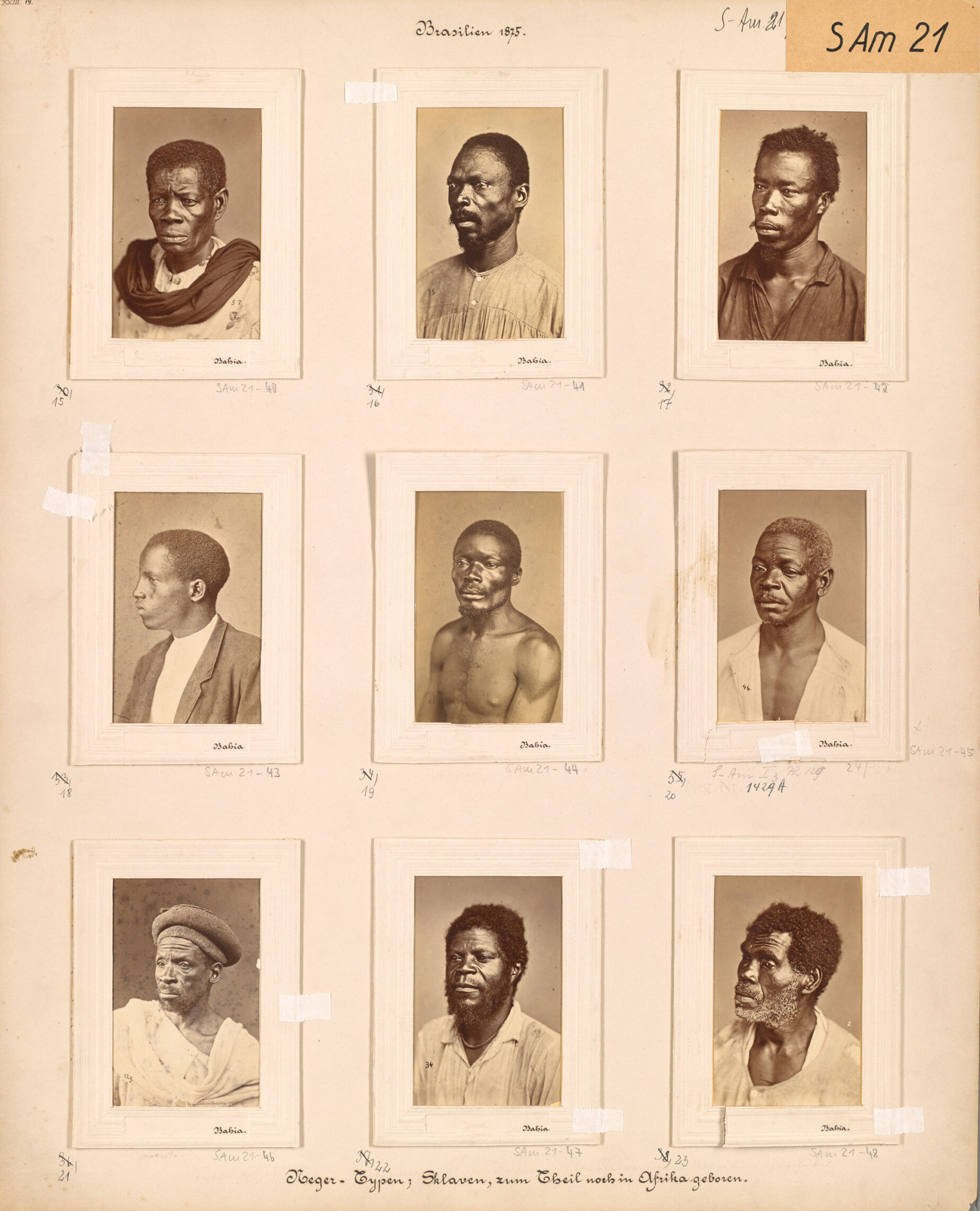

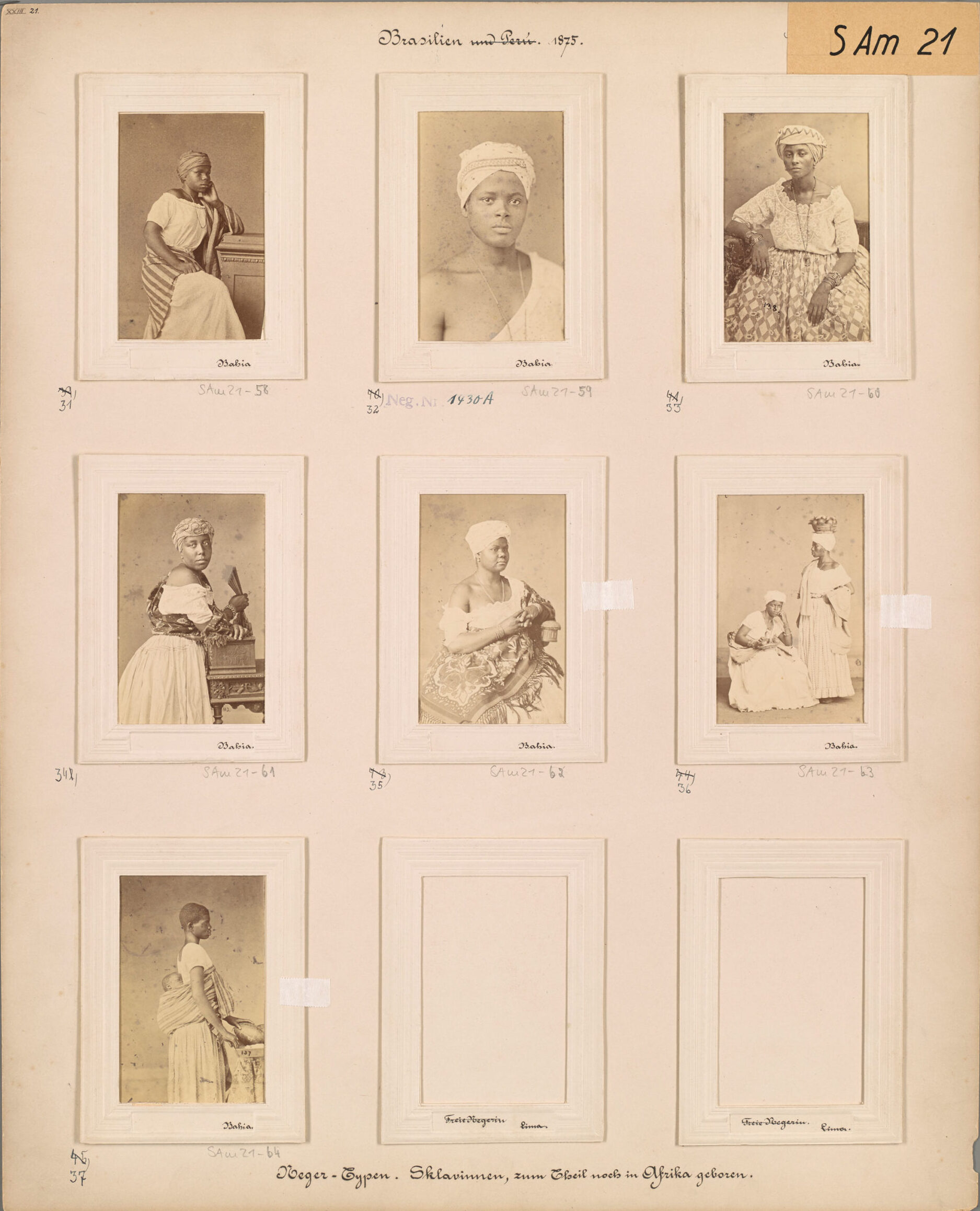

The goal of this initial reflection is to emphasize that, despite the virtual dimension of images today, we still make use of the materiality of pieces of equipment and cannot do without it to communicate. Thus, I hope to start from a reflection on how the experience with the materiality of images occurs in the 21st century to propose an examination of the portraits of African and Afro-descendant people produced by photographer Alberto Henschel (1827-1882) in the 19th-century Brazil (Figs. 1-2). These photographs were transported to Germany to be exhibited in the educational exhibition on South America organized by geographer Alphons Stübel (1835-1904). They are representations of a portion of individuals who had their images captured and commercialized in an operation that can be considered as a kind of continuation of the long transatlantic triangulation experienced by them or by their ancestors. They were moved from Africa to the Americas, as enslaved bodies, and from the Americas to Europe, as photographs of their bodies.

These people, taken as merchandise—both as human “flesh” and photographic images—, had their bodies put in evidence rather than their knowledge, histories, cultures, and perceptions of the world. The reification of these bodies is emphasized when the photographs are exhibited without identifying those portrayed from an ethnographic perspective, that is, as a resource for the hierarchical categorization of humanity, in an exhibition designed to contribute to the European colonial enterprise. In this analysis, adopting a decolonial perspective, I propose that the photographic portraits be approached by taking into consideration their power of agency over social relations. To that end, I employ Alfred Gell’s studies, in which he states that artistic objects have power of agency, that is, they have the capability of affecting social relations. The author relates the agency of artistic objects to the intentions of “human agents” (GELL, 1998, p. 17) involved in their production, consumption and circulation. Choosing this approach does not imply considering portraits—most of which in carte-de-visite format—as artistic objects. The point is, by identifying the intentions of the agents involved in the conception and organization of the above exhibition, recognizing the portraits as objects that are attributed meanings that affect social relations, considering their materiality and how they were presented.

como objetos artísticos. Trata-se de, a partir da identificação da intencionalidade dos agentes envolvidos na concepção e montagem da referida exposição, reconhecer os retratos como objetos aos quais se atribuem significados que afetam as relações sociais, considerando sua materialidade e a forma como foram apresentados.

The text arises from the urgent need to deconstruct the idea of hegemony of Eurocentric rationality established by the mechanisms of colonial power and global capitalist development, which allow daily violence—of a symbolic and physical nature—against non-white people. Thus, in order to conduct a discussion that is capable of promoting a decolonial cure of these portraits, I consider it essential to identify the dimensions of coloniality present in the curatorial proposal that resulted in their exhibition in the 19th century.

I understand decolonial cure to be a critical exercise, from a political-pedagogical perspective, that problematizes the notion of racially hierarchized humanity, legitimized with the contribution of ethnographic photography. There are myriad considerations, researches and experiences in the fields of art, education and criticism provided by African, Afro-descendant and indigenous curators who have contributed to this discussion; however, in order to constitute a theoretical foundation to this text, I use the concept of art as a cure, in the ritualistic sense proposed by Ayrson Heráclito. The author points out the need for cleansing and exorcizing the “ghosts of colonial society” (HERÁCLITO apud TESSITORE. 2018, n.p.). My intention is to establish a dialogue between Heráclito’s conception and the proposal of black artistic production, with a liberating spirit, anticipated by Abdias Nascimento in his commitment to the struggle for the “humanization of human existence“ (NASCIMENTO, 1976, p. 180).

Legenda

Legenda Alberto Henschel & Co. African and Afro-Brazilian Women, Pernambuco, c. 1869. Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography, Archive for Geography, Collection Alphons Stübel.

Legenda

Legenda Alberto Henschel & Co. Africans and Afro-Brazilians, Bahia, c. 1869. Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography, Archive for Geography, Collection Alphons Stübel.

Da trajetória transatlântica à exposição

The transatlantic triangulation of the bodies of African and Afro-descendant people through the cartes-de-visite produced in the studios of Alberto Henschel—renowned photography entrepreneur—continued via the baggage of distinguished German travelers and collectors in the 19th century. In this article, we address the portraits whose movements resulted from the expedition carried out by Alphons Stübel, who during his visit to Brazil acquired the photographs directly from the studios of Henschel.

Alphons Stübel, a German geologist and explorer, undertook a trip through South America in 1868, part of which in the company of the German researcher Wilhelm Reiss (1838-1908). The expedition, whose initial objective was to study volcanoes in Hawaii, started in Colombia and Ecuador, passed through Peru and Brazil, from where Reiss returned to Germany after falling ill. Stübel went on to Uruguay, Argentina, Chile and Bolivia, passed through Ecuador and Peru again, and ended his journey in the United States in 1877. In the following years, Stübel, in addition to other exploratory trips, dedicated himself to the creation of a museum to house the collected material and enable its organization.

In order to justify the foundation of the Geography Museum, Alphons Stübel, in a letter sent to the Leipzig City Council in 1891, explains that one of his objectives was to provide documents that could contribute to the geographical studies of the time, whose comprehension would be particularly relevant to the “colonial enterprises” of his time (STÜBEL, 1891). The museum would be organized as an archive that would preserve for posterity the production resulting from his travels, such as logs, photographs, drawings and cartographic records.

In order to carry out his project, Alphons Stübel donated to the Leipzig City Council, in 1892, his geographical collection consisting of 82 oil paintings, more than 100 drawings, around 2,000 photographs and several maps, related to the volcanic regions of South America. After this donation, in 1896 Stübel organizes the first version of the Educational Exhibition of his collection at the Leipzig Museum of Ethnology (WAGNER, 1905). Although there are no visual records of the exhibition focused on South American countries, the research carried out by Andreas Krase provides an overview of how it was organized and how Stübel intended to collaborate with the contemporary colonial enterprises. In his description, Krase reports that successions of panoramas, of different dimensions, some several meters in width, depicted sights of the countries visited. Paintings by Ecuadorian painter Rafael Troya, hired and trained by Stübel to document the expedition in Ecuador, showed the explorers’ camp with the volcanoes as a backdrop. Topographic drawings of mountain slopes, cropped especially for recording, testified to the rigor of the scientific method. The photographs documented the landscape in its natural state, the architectural interventions, the means of transportation and the native, African and European populations residing in each region (KRASE. 1985; 1994).

Figure 3 shows an angle of the Educational Exhibition already held at the Geography Museum (BERGT, 1906). The image shows that the visiting public, when taking a few steps after the entrance, could see the bust of Alphons Stübel on a pedestal. Wearing formal attire, the researcher appears amidst his legacy. The materiality of the exhibition should provide a glimpse of the world visited by Stübel without focusing on the typical setbacks of a journey in the 19th century. The traversal along this new space comprises, as in the previous one, panoramas, photographs, drawings, paintings and objects organized by countries in a standard way, that is, with a succession of images of cities, nature, architecture, means of transportation, and local and foreign populations.

Legenda

Legenda No author identification. Geographic Museum, Leipzig, 1906. Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography, Archive for Geography, Collection Alphons Stübel.

According to Andreas Krase, the photographs presented in the section on Brazil, in the 1896 version of the exhibition, showed both sights of the Imperial Palace and panoramas of the capital of Rio de Janeiro. The photos of the city showed the architecture, the port and the means of transportation, from general shots to details. In the Amazon context, some landscape photographs were also used as backgrounds in montages with portraits of indigenous people. Next, the exhibition displayed images Stübel called “photographs of types,” a series of photos of men and women, of Spanish, African and Afro-descendant origin, pasted in groups of about nine units per board. Finally, portraits of Emperor Dom Pedro II, Empress Teresa Cristina, and former president of Paraguay identified as “El Ditador López” were exhibited all on the same sheet (KRASE, 1994).

The gallery of portraits of Africans and Afro-Brazilians consisted of 54 images distributed in six passe-partout with about nine images each. Unlike those in command positions, black people did not have their images associated with their names. The classifications into types according to phenotype encompassed the groups organized by gender and social position: “Black types. Female slaves, some born in Africa,” “Black types. Male slaves, some born in Africa,” “Black types from Brazil,” and “Mixed races.”

Dimensions of coloniality

According to Andreas Krase, the approximately 2,000 photographs in the Alphons Stübel Collection were less important in the exhibition compared to the drawings and paintings. The photos served as illustrative material of the geographer’s world view about each country explored. By contrasting nature, buildings and social strata in a standardized organization across different countries, Stübel seemed to want to demonstrate a supposed fixity in hierarchized social relations (KRASE 1985; 1994).

It is based on this fixity of the presentation of society in relation to nature and the geography of South America that we will analyze both Alphons Stübel’s intention to contribute to the colonial enterprises of his time and the proposal to establish a theoretical path towards a possible decolonial cure, through photographic portraits of African and Afro-descendant people, in the present time of the 21st century.

In his studies on the matrices of the current world power, which include the forms of global domination and exploitation, Aníbal Quijano notes the fact that most of those “exploited,” “dominated,” and “discriminated against” belong to the “races,” “ethnicities,” or “nationalities” attributed to colonized populations. According to the author, the process of colonization in America naturalized these social markers, especially the notion of race, which would be the foundation of the contemporary world power structure (QUIJANO, 1992). In other words, it is through the invasion and appropriation of America by the Europeans that the development of world capitalism (modern, Eurocentric and colonial) takes place in a historical coordination with racialization as a tool of social control and hierarchizing classification of human groups.

In order to guide the connections between Alphons Stübel’s curatorial proposal in the Educational Exhibition on South America and Aníbal Quijano’s discussion about coloniality, I take as a reference the theoretical contextualization carried out by Catherine Walsh based on the work of the latter (WALSH, 2009). In her text, the author points out dimensions of coloniality that, in coordination, resulted in the current global designs of power, capital and market: the coloniality of power, the coloniality of being, the coloniality of knowledge, and the cosmogonic coloniality. The first dimension, still active in the relations of domination and subordination in the contemporary world, operated in the establishment and reinforcement of a social stratification of human groups based on the notion of race. The second dimension, through polarized binary categorizations, such as civilized/primitive, legitimized the recognition of humanity in certain groups and the denial of such humanity in others. The third dimension acted on the presupposition of Eurocentrism as a hegemonic perspective, while the fourth and last dimension pointed out by Walsh annulled philosophies, expressions of spirituality and of the sacred, as well as understandings of world of the diaspora of African and indigenous peoples, fixed in the Cartesian binary difference man/nature.

Aníbal Quijano, in turn, when addressing coloniality, explains that the supposed natural superiority of whites—mainly Europeans—was expressed in a “mental operation of fundamental importance for the entire pattern of world power, especially with regard to intersubjective relations” (QUIJANO, 2005, p. 120). It is in this mental operation that I observe the agency of portraits of human types in the educational exhibition on South America, geared toward the European public in general and toward specialists interested in preparing for journeys and research similar to those of Stübel.

In the exhibition, the photographs act so as to transform the intersubjective relations of Europeans with one another, and of Europeans with non-Europeans. When seen in an organization that fixes the social positions of groups categorized by race, the portraits inform visitors about the position of domination reserved for them and of subordination reserved for non-Europeans, materializing the coloniality of power. The primitive/civilized, traditional/modern, magical/scientific, European/African binary oppositions,

—perceived in the comparison between the portraits of black and white persons—legitimize the rational/irrational, human/inhuman polarization, in which we can observe the coloniality of being. As a consequence, the portraits operate in the intersubjective relations between whites and non-whites, and between them and Africans and indigenous people, the former being taken as producers of knowledge and the others taken as an object of study, representing the coloniality of knowledge.

Finally, interrelated to the previous ones and as important as they are, is the coloniality of mother nature, the so-called cosmogonic coloniality, which concerns the invalidation of the ethical, philosophical and spiritual principles of indigenous and Afro-diasporic communities. Fixed in the Cartesian binarism between humanity and nature, this operation of coloniality nullifies the spiritual and sacred perceptions of the world that understand the earthly world as intrinsically connected with the spiritual world, and that recognize the land and ancestors as living beings. The annulment of the rationality and practices of existence of African and Afro-descendant populations occurs when they are categorized by colonial discourse as non-modern and “pagan” (WALSH, 2009).

In the portraits, we find this form of annulment when we observe, for example, elements typical of the Afro-Brazilian sacred sphere, such as the turban, being shown only as a certain pattern of the way of dressing, when in fact it is a piece of clothing called torço in Candomblé terreiros, which has the function of protecting the ori of the person who wears it. The same could be said of the quipás worn by male figures, or the back cloths. These, along with the turbans, according to the ties, keep information about the person’s hierarchical position in the terreiro and their relationship with the orishas. The lack of information about the fact that turbans and back cloths constitute part of practices of sacred existence of the people portrayed leads to a type of agency of the images on the visiting public, which is led to see black bodies, deprived of their individual and collective identities.

We can mention another example (Fig. 4), in which clothes are used as an organization criterion, referring to the cultural aspect in a standardized and somewhat exotic manner, or even contributing to the eroticization of bodies. Employing a typically western fan, the young woman in the first image, located in the second line, leans on a piece of furniture, resorting to a pose characteristic of non-ethnographic portraits, often used for the construction and valuation of the social identity of a white woman in the 19th century. Despite the fan and furniture, the young woman’s turban and attire show her non-Western origin and culture; nevertheless, her bare shoulder affords eroticism to the pose. The portrait, as part of the series called “Black Types. Female slaves, some born in Africa,” leaves no doubt about the social and gender position attributed to the woman portrayed.

Legenda

Legenda Alberto Henschel & Co. Afro-Brazilians, Bahia, c. 1869. Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography, Archive for Geography, Collection Alphons Stübel

Decolonial Cure

By connecting some aspects of the Educational Exhibition on South America—where the series of portraits of Africans and Afro-Brazilians produced by Alberto Henschel was exhibited—with the dimensions of colonial power discussed by Aníbal Quijano, I sought to demonstrate that the curatorial organization of Alphons Stübel attributed an informative character to the portraits, based on the notion of race, aiming to establish a position of inferiority of this group of people in the world scale of power. Thus, if this analysis proves relevant, we can conclude that the agency power of the “racial type” photographs in the exhibition consisted in justifying the slaveholding basis of the colonial economic structure that—as Quijano explains—structured the development of the contemporary global capitalism. In this process, the portraits contributed to the erasure of African and Afro-Brazilian stories, knowledge and cultures, at the same time that they highlighted the bodies of black people as bodies devoid of subjectivity.

*

To finish this article with a proposal for a decolonial cure of the portraits analyzed here, I divert my gaze from the computer screen and write by hand in my notebook. This gesture reminds me of my initial reflection on the materiality of electronic devices that we use to communicate securely today. The physical security of virtual communication, however, does not apply to our sanity. Western civilizing rationality, which locates human reason solely in the mind, ignores ancestral knowledge of African origin, which recognizes the head as a place of spirituality and knowledge, and defines the body as an instrument for expression of sacred knowledge. We are whole bodies. We are collective bodies. Viewing our faces through electronic pulses on screens is not enough to communicate who we are. Similarly, as we have seen, the portraits of types of African and Afro-descendant people, in the exhibition organized by Stübel, failed to show to the European world the alternative of a non-Western rationality, possessing a humanity that is one not only with nature, but also with ancestors and descendants.

As a benchmark for the decolonial cure of these portraits, I propose the observation of the transatlantic movement made by Ayrson Heráclito between Brazil and Senegal to carry out performances in two architectural monuments related to slave trade and colonial power: O Sacodimento da Casa da Torre, in Bahia, and O Sacodimento da Maison des Esclaves (Casa dos Escravos), in Île de Gorée (2015). Heráclito, as ogã sojatin de um humpame de Jeje-Maí, in the city of Salvador, has authority for the sacodimentos (shakings), cleansing rituals practiced with sacred leaves. By performing this spiritual cleansing in architectural structures that are symbols of the dehumanization of African populations, the priest/artist uses pre-colonial African knowledge to exorcise the violence conducted by European civilizing rationality in the past, but still active in the present. I propose the association of Heráclito’s performance with the project of Abdias Nascimento, who advocated a black artistic production with a liberating spirit that would make clear to the world that the memory of Afro-Brazilians predates the beginnings of the enslavement of Africans in the 15th century and the transatlantic slave trade (NASCIMENTO, n.d). I believe that the political-pedagogical function of this decolonial cure consists in contributing to the transformation of contemporary intersubjective relations, so as to break the fixity of the social and class structure built through the racialization and hierarchization of humanity.

Having recognized the ethnographic portraits in their role as agents of colonialism, as well as the architectural monuments exorcised by Heráclito, it is incumbent upon us to determine the appropriate purification rituals for their decolonial cure. Thus, I propose the exorcism of the coloniality expressed in the portraits called “types,” by excluding this term from the caption of these images in their future circulations. In order to commence the attempt to (re)construct the identities of the persons portrayed, the suggestion is to replace the racial denominations—which are characteristic of the discourse of whitening of black populations (mixed, mulatto, cafuso (zambo), brown)—by updating them to Afro-descendants, Afro-diasporic, Afro-Brazilians. Associated with the gesture of renaming, my proposal is to resort to research and the exercise of imagination to trace—by means of the materiality of the objects present in the images (fabrics, clothes, prints, hats, quipás, turbans, back cloths, jewels etc.) to which cultural and sacred practices the people portrayed belonged. It is also important to seek to reconstruct the circulation of portraits in Brazil in the 19th century to learn, as much as possible, the name and history of these people.

I hope that such shakings will clear the weight of the colonial dimensions from the images in order to liberate the humanity of the people encapsulated in the 19th-century ethnographic portraits. Humanity that, despite the objectification of bodies, never ceased to exist.

May Exu grant us open paths.

References

BERGT, Walther. Die Abteilung für Vergleichende Länderkunde am Städtischen Museum für Völkerkunde zu Leipzig. Jahrbuch des Museum für Völkerkunde zu Leipzig. Leipzig: Voigtländer, 1906.

GELL, Alfred. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998.

HENSCHEL, Alberto e Co. Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography, Archive for Geography. c. 1869. Available: https://leibniz-ifl.de/forschung/forschungsinfrastrukturen/digitale-sammlungen/collection-alphons-stuebel. Access in: Feb. 28th, 2022.

HERÁCLITO, Ayrson. apud. TESSITORE, Mariana.Ayrson Heráclito, um artista exorcista. Arte ! Brasileiros. jun. 2018. Available: https://artebrasileiros.com.br/sub-home2/ayrson-heraclito-um-artista-exorcista/Access in: Feb. 28th, 2022.

KRASE, Andreas. Von der Wilderheit der Szenerie eine Deutliche Vorstellung . (Dissertação de Mestrado) – Bereich Kunstwissenscheft. Berlin Humboldt-Universität, 1985.

KRASE, Andreas. Von der Wildheit der Scenerie eine Deutliche Vorstellung: die Fotografiesammlung von Alphons Stübel und Wilhelm Reiss aus Lateinamerika 1868 – 1877. Spurensuche, 1994, p. 145 – 158.

KOHL, Frank Stephan. Um olhar europeu em 2000 Imagens: Alphons Stübel e sua coleção de Fotografias da América do Sul. Studium, n. 21, jun. 2005, p. 5174. Available: https://econtents.bc.unicamp.br/inpec/index.php/studium/article/view/12221. Access in: Feb. 28th, 2022.

NASCIMENTO, Abdias. Arte Afro-brasileira. Black Art: an International Quarterly, New York, 1976.

NASCIMENTO, Abdias . O quilombismo. In: Afrodiáspora 5 e 6. Revista do Mundo Negro. Ipeafro, PUC SP, ano 3, n. 6 e 7, 1985. p. 2140. Available: https://issuu.com/institutopesquisaestudosafrobrasile/docs/afrodi_spora_-_volume_6_e_7. Access in: Feb. 28th, 2022.

PRATES, Lubi. Um Corpo Negro. São Paulo: Nosostros Editorial, 2019.

QUIJANO, Aníbal. Colonialidade do Poder, Eurocentrismo e América Latina. In: A Colonialidade do Saber: Eurocentrismo e Ciências Sociais. Perspectivas Latino-americanas. Buenos Aires: CLACSO, Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales, 2005, p. 117142.

QUIJANO, Aníbal. Colonialidad y Modernidad/Racionalidad. Perú Indígena, v. 13, n. 29, Lima: Instituto Indigenista, 1992.

TURAZZI, M. Inez. Poses e Trejeitos: a Fotografia e as Exposições na Era do Espetáculo (1839 – 1889). Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 1995.

WAGNER, Paul. Illustrierter Führer Durch das Museum für Länderkunde (Alphons Stübel-Stiftung). Leipzig: Museum Für Völkerkunde, 1905.

WALSH, Catherine. Interculturalidade Crítica e Pedagogia Decolonial: In-surgir, Re-existir e Re-viver. In: MARIA, Vera.(org.). Educação Intercultural na América Latina: entre Concepções, Tensões e Propostas. Rio de Janeiro: 7 Letras. 2009, p. 1243.